< home < content next: Valeriy Gerlovin Objects >

RIMMA GERLOVINA AND VALERIY GERLOVIN

TRESPASSING

(A SHORT OVERVIEW OF THE ARTWORK)

© 2010, Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin

PART 2: RIMMA GERLOVINA THE CUBES

In 1972, Rimma began to experiment with her visual prose, typing it into specific patterns. From that she quickly moved on to scores of visual poetry intended for simultaneous reading by several voices, arranged in a sort of spoken opera. Some of these scores were written in different Slavic languages. As a student at Moscow State University, where she majored in Slavic studies, she turned the subject of her education into a creative tool. The search for the exact form seemed to be a way to enter into another dimension of conceptual poetry. And in 1974, the little cubes, portable objects of three-dimensional poetry, burst forth as if from a fountain, overflowing our entire apartment in Moscow.

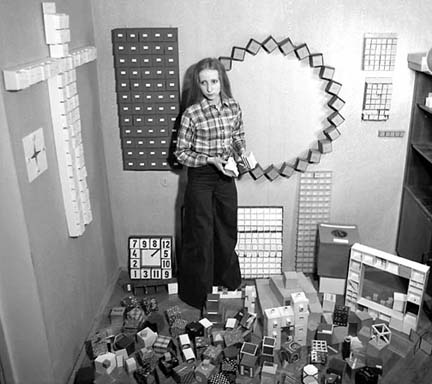

Rimma Gerlovina with the cubes 1974-6, Moscow. |

The solid form of the cube has traditionally been used to symbolize the material substance of the world, which is precisely the place where the hidden creative force operates. Bearing the elements of poetry set up into the art object, the cubes are like materialized works of haiku speaking with metaphorical clarity, and yet preserving their ambiguity. A paradoxical simplicity in combination with an analytical approach, lyrical irony, and a fatalistic element organize, so to speak, the semantic environment of the cubic organisms. The characters of the homo-cubes (as they have sometimes been referred to) - especially those that talk as dramatis personae - are symbolically revealed as if in an anatomical theater: not nude, but naked. All of these early works were made in the same breath, and the very first cube, Quintessence, created in 1974, is one of the initial sparks, and perhaps the most informative.

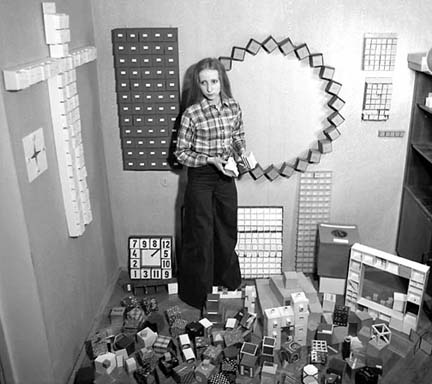

Rimma Gerlovina, Quintessence: "above me" is written on the inside lid, "below me" on the bottom, and "in front of me" on each side. 1974, cardboard, paper, fabric, acrylic, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼" or 8 x 8 x 8 cm. |

In this conceptual poem we hear only its voice in the first person, which determines its location in space by the projected inscriptions "above me," "below me," and "around me." The work comes as a sound of an Aeolian harp without the assistance of a player, and becomes a witness of another intangible dimension right in the middle of the tangible sides of the cube. In a poetic sense, quintessence is the voice of consciousness that a priori knows the mystery in which we all are situated, much like in this cube.

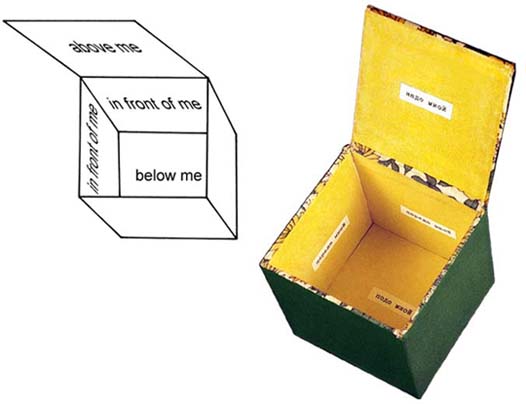

In mythology, the truth was always veiled by parables and images in order to preserve it from an unprepared eye, which tends to distort it. With some kind of ironic twist, the lid of the cube The Soul. Do not open. It can fly away! covers the age-old secret, as if with an aesthetic veil preventing it from misinterpretation. As soon as man tries to grasp the idea logically, its essence is diluted. The uttered thought reflects the truth only partly, especially in such a delicate case; therefore, any curious eye meets the predictable result, "There it goes!"

Rimma Gerlovina, The Soul: "The Soul. Do not open, it can fly away!" is written on the lid, "There it goes!" appears inside, 1974, cardboard, paper, fabric, acrylic, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼". |

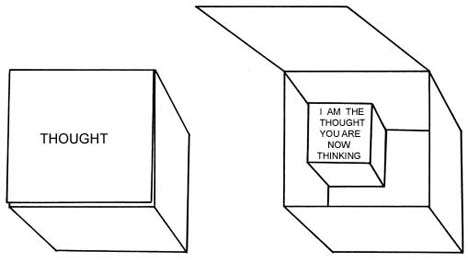

The cubic concepts are generally clothed in small boxes or other geometrical bodies, which contain text on the interior and/or exterior. Serving as allegorical units of time, space, or human character, they are specimens of a noetic, interactive form of three-dimensional poetry that gains new corporeal habitation in the cubes. The cubes seem to have a gift for communicating abstruse arguments to intelligent laymen. The lyrical message prompts not only reading but also literally a psychosomatic examination of these solid bodies, which, in turn, often provokes the spectator's capacity for postulating and doubting. At first, reason steps in and for the most part overcomes feeling. However, the irrational element implicit in the design of these concepts leads sophistry into a trap: If one opens the cube containing "my thought" on the lid, what would be the answer to its interior question?

Perhaps it would be better to use the description of these works in Artforum magazine provided by our fellow artists Komar and Melamid, who happened to witness their circulation in Moscow:

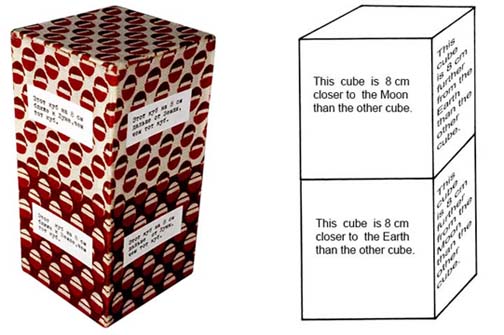

Some of the cubes, large and small, bear labels describing their particular qualities, either from the author's or the cube's point of view. For example: "This cube is 8 centimeters closer to the Moon than this one" - they speak in ambiguities. |

Rimma Gerlovina, Moon - Earth: The text "This cube is 8 cm closer to the Moon than the other cube" is written on the upper cube, on the lower cube: "This cube is 8 cm closer to the Earth than the other cube." 1974, cardboard, fabric 3¼ x 3¼ x 6 ½" or 8 x 8 x16 cm. |

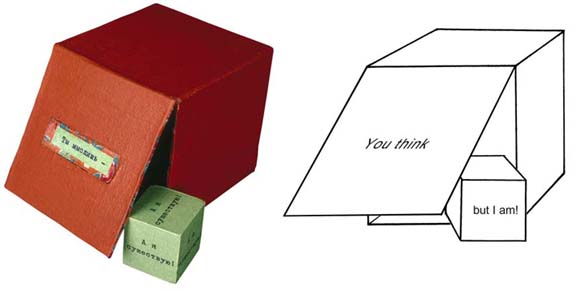

Box: "There's a sphere inside me." The inside of the cube: "He's a sphere. I'm a cube." Box: "You think." Small cube inside: "But I am." This is not a dialogue, but a monologue in which the inside plays the role of an inner voice. Here we are face to face with the dichotomy of the Homo-Box's consciousness. The only woman in contemporary Russian Modernism exhibits a profound inventiveness in designing a wardrobe for her soul. (1) |

In the seventies, the cubes looked like a new symbolic language stationed on the border between poetry and art. As any provisional base has to be tested experimentally, we will give a picture of the surrounding situation and the vox populi of that distant time. People often reacted with witty enthusiasm to the cubes in a reflexive response to their stimulating ideas; on one occasion the poet Genrikh Sapgir spontaneously versified his psychological observation: "Yourself as her cube, she multiplies." Some went further in their theoretical scrutiny, especially the scientists who frequently came to our home as if to a gallery. During this period, the official exhibition of our conceptual work would have been impossible. Instead, we and other fellow artists thrived on the unofficial, usually group, exhibitions in our apartments. For the moment, it was a sort of underground institution, which was constantly in conflict with the authorities. Here, as a result of many gatherings with our friends, many subversive ideas and projects were born, among them A-Ya, the first magazine on contemporary Russian art, which was later published in Paris.

How the Eastern European Biennial influenced our lives we've already mentioned: after Rimma's cubes were shown in the next international Biennial in 1978, the time came for us to pack. We distributed some of our works among friends; many artists let us choose their works for our collection, while Eric Bulatov drew Rimma's portrait as a gift. It seems that the poet Vsevolod Nekrasov - who used to call Rimma "the grandmother of Russian conceptualism" in jest because of her young age - expressed the general feeling of our friends with his usual metaphorical brevity: "And you lessen our number." Our last evening was as merry and wild as Finnegan's Wake. With this we shall break away from the world of long-past events and enter that of creative ideas.

The nature of changing and unchanging invites explanations and demonstrations as to what they are about. We do not want to say in many words what one or two ably would. The cubes are precisely the form that permits shortening the method of exposition to a three-dimensional formula. For example, the Descartes axiom "I think, therefore I am" paraphrased into "You think, but I am" and presented in a cubical form brings another twist to its meaning.

Rimma Gerlovina, You Think but I Am: "You think" is written on the lid. "But I am!" appears on the inner cube. 1974, cardboard, paper, fabric, acrylic, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼". |

Does human rationality have the power to transcend human finitude? The mind is always in a state of flux and yet wants to be the measure of all things. With a logically coherent metaphysical structure, one can hope to understand everything in nature, but not nature itself. It seems that genuinely clear thought can objectify itself in spontaneous understanding only if intellectual contortions are subdued by intuitive simplicity, and that is not a new, learned tool but an awakened a priori part of our consciousness. Revealed in the sum of every natural and human event, intuition is qualitatively different from instinct. To the untrained eye, the two look alike, but it is not so. Instinct is below the rational, intuition is above it. Instinct revolts against the conscious, orderly approach, while intuition peacefully subdues it.

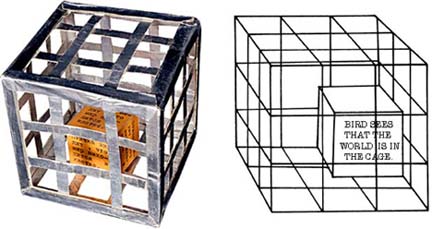

Rimma Gerlovina, The Cage : "The Bird Sees That the World is in the Cage" appears on the smaller cube inside. 1974, cardboard, wood, paper, foil, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼". |

Sitting inside its silver cage, the yellow bird sees that the world is in the cage. People wrestle with contradictions on the subjective side no less than on the objective one. The idea of a cage-cube certainly is a mental concept. Human intelligence is related to the plane of matter as its environment and support; therefore, all cages are different in accordance with the peculiarities of the psychological dispositions of their inhabitants. Many ideas of our early works found their further expression in our later performances, sculptures, and finally in our conceptual photography. The image of Bird, made fifteen years after The Cage, clearly points to the same metaphor.

Rimma Gerlovina, Valeriy Gerlovin, Bird, ©1989, C-print. |

There are certain moments in life that bring to mind a bird (a traditional image of the soul) beating its wings against the bars of its cage. The ideas associated with flying, or rather, levitation as opposed to gravitation, were already implicit in Rimma's concept of the "floating" exposition of the cubes. These works were exhibited in 1979 in the Nächst St. Stephan Gallery, Vienna, hanging by strings from the ceiling, thereby organizing visually a sort of miniature galactic space.

Rimma Gerlovina, installation view of the cubes in Nächst St. Stephan Gallery, Vienna, Austria, 1979. |

Wandering among these small "floating" bodies, spectators could manipulate every cube. Many years later, we came across a similar image in a passage of C. G. Jung: "it seemed to me as if behind the horizon of the cosmos a three-dimensional world had been artificially built up, in which each person sat by himself in a little box... and now it had come about that I - along with everyone else - would again be hung up in a box by a thread." (2)

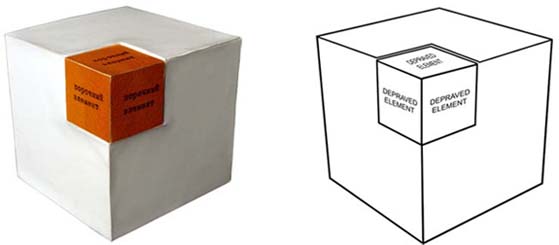

The casuistic duality of nature can be illustrated by many means. The white cube with the orange "depraved element" is one of the early examples.

Rimma Gerlovina, Depraved Element: With the removal of the small orange cube titled "Depraved Element," the perfect shape of the white cube, one of the five absolute Platonic solids, is destroyed. 1974, cardboard, wood, paper, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼". |

As a cube, it represents one of the five absolute Platonic solids. However, if one removes the small orange block symbolizing a depraved element the perfect shape of that body is ruined. Every truth has a grain of mistake, and every mistake can have a grain of truth. When the ancient Chinese masters made their art objects, they used to add a tiny, almost invisible dent; they thought that the nature of our earth does not tolerate perfection, and that if they themselves did not make a slight damage to their work, nature would interfere in a much worse way. The world is full; there are no empty niches; and a definite hierarchy governs the scope of ideas, beings, and things. And some of them can be quite depraved.

![]()

Rimma Gerlovina, Icon: The cells code an archetypal destiny of a man. 1974, cardboard, wood, paper, acrylic, 19¼ x 18½ x 3". Collection of Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers University, NJ. |

The white color is a not less meaningful feature of the three-dimensional poem called Icon. Twenty conceptual scenes of that icon unfold into a biography of a person, whose image is supposed to occupy the center of the composition. That place is left empty, signifying that it is reserved not for one particular individual but for the archetype. In the hagiographical structure of the icon, each cell suits the corresponding coded level of consciousness. This pictographical biography is kept within one opus circulatorum, which has many layers and many rounds but one uniting center. The idea of the progressive opening of the consciousness develops like a child that has to aggregate his parts in the womb until the moment when he is ready to "jump out." That is precisely what is shown in the last cell of Icon, which does not have a back wall; its frontal lid covers the mystery of abyss - the grave is empty.

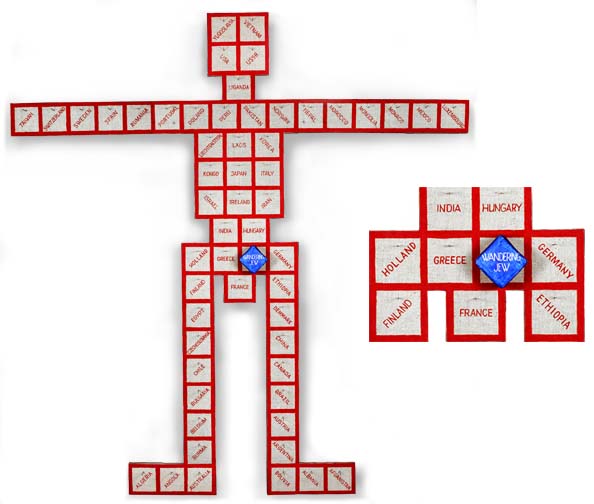

The life of an artist usually has many twists and turns; in a way, it is a happening in itself. From the point of view of an ordinary person, it looks rather like a "mishappening," as in Rimma's series of Cube-Environments (1975), in which the spectator is turned into a performer. Among them, Expeller is particularly significant. It demonstrates the paradigm of an objective process, a kind of deliverance from nature's constraints. It is conceived and played out by nature itself, wherein the personal ego is slowly processed by the power of the impersonal, similarly to a rough diamond getting a brilliant cut. In strictly conceptual form, it shows both the process and the outcome.

After that series of cube-environments and a cluster of multi-cell objects such as Pyramid, Paradise - Purgatory - Hell, and Apartment House, the molecular structure of the cubes was bit-by-bit transformed into the human-size figures.

Rimma Gerlovina, Paradise - Purgatory - Hell: The spectator can group 60 cubes with names of famous people into three categories, passing the judgments on the condition that only names are mortal. The set of the celebrities includes: Socrates, Nefertiti, Galileo, Joan of Arc, Nietzsche, Napoleon, Raphael, Nobel, Confucius, Lincoln, Freud, Stalin, Picasso, Bakunin, Ramses XVI, Gagarin, the Beatles, Dante, the expert in afterlife judgment, and others. 1976, wood, cardboard, paper, 22 x 16½ x 1¼". Collection of The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia. |

Like in a biological process, the small cubic cells grew into big cubic organisms. The first member of the family of humanoids was made in 1976, and shortly after we moved to New York in 1980, the first Interchangeable Man was recreated in full color, larger than life, and with additional progeny.

Rimma Gerlovina, Interchangeable People, 1981-82, wood, canvas, foam, acrylic, 77 x 72 x 5" and 35 x 32 x 4". |

These human figures with outstretched arms are made of soft, fleshy cubes; each has text on every side, addressing a range of concepts from positive to negative meaning, for example, "rational - realistic - normal - queer - abnormal - crazy." Through the cubes, it is possible to trace the line from genius to stupid, from saint to devil, and so on. The spectator has the opportunity to rearrange the cubes, creating a personality in his own image or writing his own random poetry. Each cube contains the word "normal," to create a totally "normal" anybody. The work is based on the paradox that while man is a process of fate, he can overcome that process through well-directed personal effort. In general, the cubes can be used as an accurate psychological device to categorize people.

In terms of their structural compositions and primary colors, the series of Cubic Organisms continues the traditions of Russian Constructivism, but with a completely new verbal twist imbedded in their psychological, philosophical, and metaphysical context. In addition, their interchangeable structure permits the spectator's active communication with the objects in a spirit of playful participation. The series features more than twenty large conceptual sculptures including those in pictographic hieratic poses with interactive content. For example, Dog-Calendar consists of one hundred cubes, each representing a year, with six different prognoses written on each side of every cube. The year 2009 has the possibilities "occurrence - erosion - experiment - excess - relax - chaos," while 2076 suggests the following alternatives: "comprehension - misconception - leisure - propriety - alliance - chaos."

Rimma Gerlovina, Dog-Calendar, 1982, wood, canvas, foam, acrylic, 68 x 59 x 5". |

Manipulating these soft cubes, the viewer creates his own model of a time-life concept. One may generate one hundred years of total chaos, since that concept is included in every set of six possibilities. The model of random order presented in this dog-sphinx contains in its potential all options, stored in the so-called organized chaos.

In the anthropomorphic sculpture Man of Babel (1983) each side of every cube has a letter from one of six alphabets: Sanskrit, Chinese, Hebrew, Arabic, English, and Cyrillic. The multilingual crowd of cubes is incorporated into the red frame of a body seated in the pose of a pharaoh. The spectator can turn and toss the cubes, creating actual words or engaging in the art of lettrism. As an anthropomorphic metaphor for the Tower of Babel, this work reflects the multinational environment of New York, our contemporary Babylon - this conglomerate of everything from everywhere, in which all is branded as normal, even the most abnormal.

Rimma Gerlovina, Man of Babel, 1983, wood, canvas, foam, acrylic, 46 x 69 x 5". |

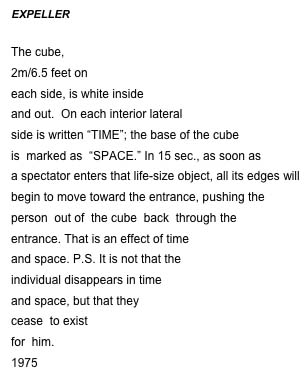

The oversize figure of The Wandering Jew (1982) is divided into squares representing different countries. The viewer can move the soft blue cube marked as "Wandering Jew" (symbolic of emigration among others) over the map of the world, hanging him by the nails that are sticking out on every country-square.

Rimma Gerlovina, The Wandering Jew, full figure and close-up. 1982, wood, canvas, nails, bell, foam, acrylic, 85 x 90 x 5". Collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art Art4RU, Moscow, Russia. |

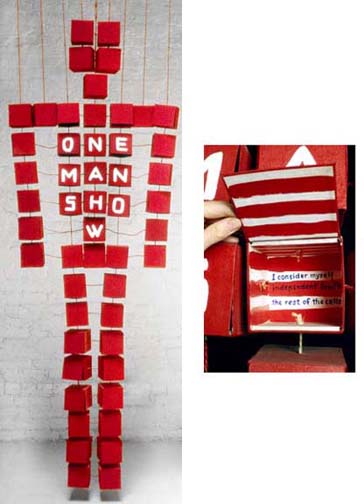

One-Man Show (1982) is also a large red man, hanging by a string from the ceiling. Like an organism that consists of many cells and a plurality of thoughts, that suspended individual is composed of fifty-one separate cubes united by one string. Each cube can be opened and contemplated; each cell holds a clue to some life experience. For example, the central interconnected cube with the interior text "I consider myself independent from the rest of the cells" suggests one of the typical individualistic thoughts that contrast with the reality of an incessant patchwork quilt of interdependence.

Rimma Gerlovina, One-Man Show, full figure and close-up. 1982, cardboard, canvas, wood, string, acrylic, 89 x 31 x 4". |

Summarizing general components and concepts, Rimma defined the principles behind all the cubic works in her theory of Transfism, which consists of the following theses:

1) Archetypal units and principles (cubes or other geometrical bodies and linguistic formulas); 2) Metaphorical games (as a symbolic modeling of the world and an a priori part of human nature); 3) Interchangeability (of time, space, sex, as a basic principle of life, and the unity of opposites); and 4) Co-creativity (of the spectator, who continues the flux of changes in the work). |

Rimma Gerlovina, Cubic Organisms, installation view of the joint retrospective exhibition An Organic Union at Fine Arts Museum of Long Island, Hempstead, NY, 1991. |

Beginning in 1974 with the cubes, those portable philosophic units, Rimma arrived at the circles in 1987, lingering for some time in between with the transitional series of Shifting Objects of 1984-86 (Sunset, Live-Dead, The Last Supper, The Shadow, among others).

Rimma Gerlovina, Sun Set: The Celtic cross is shown in two positions: as "sun set" and if shifted as "sin sweet." 1987, wood, acrylic, 51 x 31 x 5". |

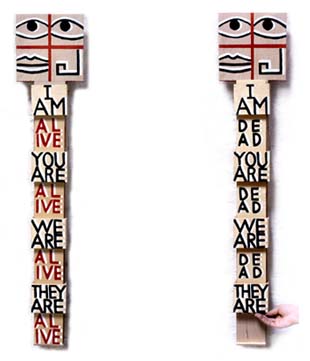

Rimma Gerlovina, Live - Dead: the work is shown in two positions. 1986, wood, acrylic, 40 x 8 x 3½". |

There is an ancient dilemma behind the idea of the squaring of the circle, or, in her case, the circling of the square. That geometric operation has baffled many mathematicians and even more theologians (who viewed the soul as a circle that occupies the square of the body). As a symbol of the transcendent the circle is free from the bondage of the corners that organize the square and the cube. The square implies not only the basic arrangement of the world, but humans' constructive attempt to achieve permanence in material life. Yet amid the flux of nature, only change itself is unchanging. Nature's permanence is akin to a limitless circle that can be traced in an orderly repetitive motion: from the orbs of the planets to a single drop of rain. In medieval thought, God is a circle whose center is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere. Thus in ancient sacred architecture and in every scheme of cosmological geometry, the square and the circle are brought together and made commensurate.

Rimma Gerlovina, Circles, 1988. |

The round concept Fortune can be traced in three consequent positions: closed, as fortune; half opened, as misfortune; and fully opened - as misfortuneless. The wheel of fortune is itself a game of perpetual paradox. In a similar manner, when Fortune is closed it keeps all its mystery intact, much like a Pandora's box.

Rimma Gerlovina, Fortune, shown in two positions.The work opens in the following sequence: "fortune" - "misfortune" - "misfortuneless." 1988, wood, acrylic, 13¾ x 13¾ x 2¼". |

As soon as we open the first door, the powers of fortune start to cross and crisscross life, admitting man into the great ritual drama called "misfortune." Here we stand before that mental door that the average man is afraid to open, the door that perpetually enters into itself and leads to "the way on which there is no traveling." The direct experience might be quite turbulent, filled with the unforeseen animosity of the surroundings. Then the second door can be opened. It leads to the full outcome of the experience and reshapes the previous malformation. The blind thesis of fortune followed by the antithesis of misfortune is resolved in the fully conscious synthesis or union of opposites - in the misfortuneless. It is like arriving at a state of fullness after passing through emptiness. Genuine fullness cannot be full unless it includes emptiness as well.

Rimma Gerlovina, Before - After, shown in two positions. If opened, it reads "before birth" and "after death." 1988, wood, acrylic, 13¾ x 13¾ x 2¼". |

The trajectory of the three-dimensional concepts began in 1974 from the cubes, these portable semi-philosophic units that filled up our bookshelves in Moscow. In 1987, the talking platonic bodies became rounded: the cubes evolved into the circles. Coming into qualitatively different space and another time zone of our life, we kept seeing our art as a subject-in-process. Furthermore, art and artists "suffer" the process together. While Rimma's multi-celled Cubic Organisms passed through the stages of the progressive transition towards the circle, Valery's metal sculptures were also made into round shapes, exploring the sign language of universality akin to universality of the melodies. We were simultaneously drawn to forms that corresponded to ideas, particularly circles. If Rimma was versatile predominantly with the word-concepts, Valeriy was at home with the archetypal forms - as if she employed the algebraic method of conceptualism, while he preferred the geometric one.

Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, view of the loft, New York, 1993. |

-------------------------------------

1 Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid, " The Barren Flowers of Evil," Artforum (March 1980): 51. 2 C. G. Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections (New York: Vintage Books, 1973), 292.

|

LINKS:

< home < content next: Valeriy Gerlovin Objects>