< home < content back to The Cubes >

RIMMA GERLOVINA

Early Visual and Polyphonic poetry

© 2010, Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin

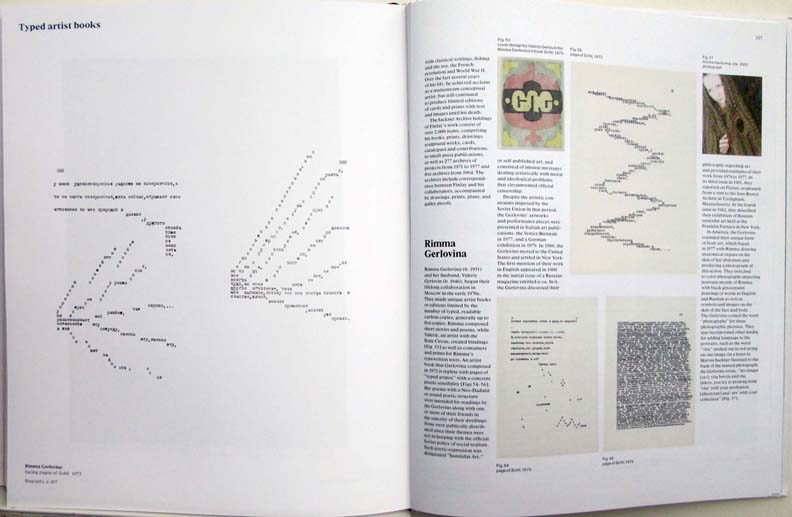

Before the cubes came into life, the experiments with visual prose and poetry preceded these sparks of conceptual imagination that appeared as flashes of an immediate experience "boxed" in the cubes. In attempt to give a visual history of that hour, it may be mentioned that all early typewritten visual prose and poetry were written in different patterns and issued as handmade books. Almost all of them contain graphic works by Valeriy, to be precise, the monoprints made with the help of color carbon paper. Visual novels Sle, (1972) and On the Wind (1973) are written as a stream of conciseness; in a way, it is a language of nature itself, expressive in its wilderness and its latent omniscience, filled up with pauses, lulls, and blowing in gusts. The polilogues are presented as stenographic copies, reflecting word-by-word conversation, including hesitations, interjections, and mumbling.

| Rimma Gerlovina, Sle (“Сле“), 1973, Moscow. Cover (carbon paper monoprint) by Valeriy Gerlovin. The Sackner Archive of Concrete and Visual Poetry, Miami, USA. |

About the print on the cover. The process Valerliy used to produce this graphical work is rather unusual: maneuvering pressure and heat under different angles he transferred waxy pigments of color carbon paper onto the monoprints in a variety of shades and lines. Many his inventions were done not with wild spontaneity but with a sense of an unforced natural simplicity, such as stamping, making flat color patterns through the carbon paper tissues with a regular household iron or linear drawings with its edge. It is not ironing per se, but rather a figure skating with an iron. The soft slightly faded colors harmonize with the rough grains of paper sheets, reminding old engravings and woodcuts. That color carbon technique seems to be a good match to the modes and methods of the underground art in Russia in general and the genre of samizdat art in particular. In the era of typewriters, it was a useful tool in production of our handmade books that contain many carbon paper images, adorning even their cloth bindings.

| Rimma Gerlovina, reproduction of several pages from “Sle” in book "The Art of Typewriting", Marvin and Ruth Sackner, Thames & Hudson, 2015. |

About the title “Sle: if it is read as two words “S Le” it means “With Le” (Le is short of Valeriy.) Also, “Sle” is the first three letters of the novel in the word "slepit," ("blinds,") which three last letters "...pit" end the novel. In English the title would be "Bli", the novel begins with "...nds the light" and ends with “…nds.” The split is supposed to create an uninterrupted sequence, in which the title and the content are not separated. All-in-one flux

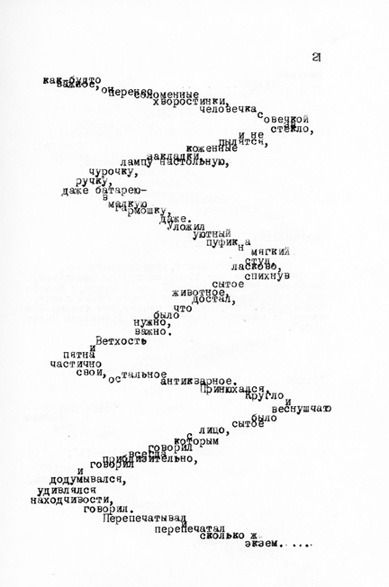

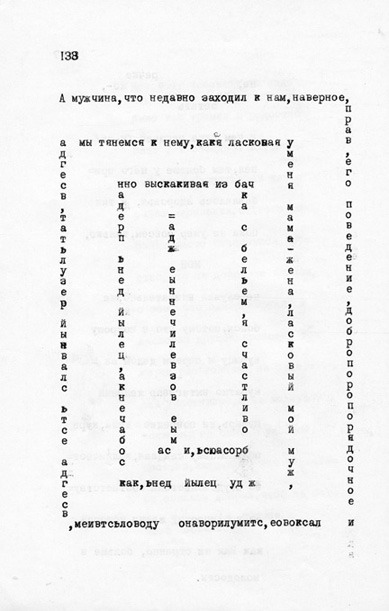

Sle is an experiment with visual prose, typed on the vintage “Underwood. ”To translate this book is very difficult if not impossible, instead we suggest the descriptive rendering of some pages.

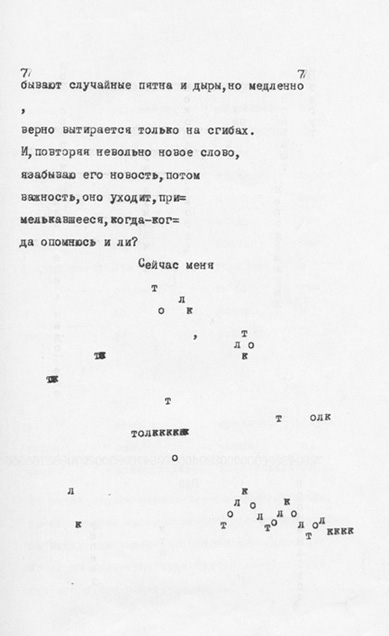

Page 7. The sentence “Somebody pushed me” is dissipated. The “push” is expressed in the series of interrupted impulses. The clumsy disorganized push.

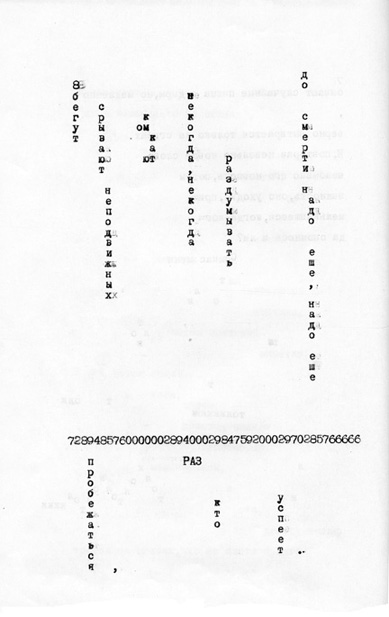

Page 8. The vertical words express running: “I run… no time to think… before I die I have to run many times” The horizontal line of number… with its last ominous digitals – 66666 indicates an obstacle.

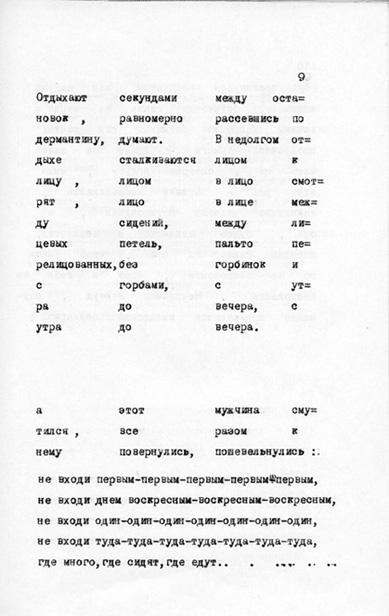

Page 9. Rows of people in Moscow subway. They are sitting and watching each other, from morning to evening. Their coats are not new.

Then, the pause–the empty space on the page. Someone enters the car, and everybody look at him reprovingly. The choral voices of the crowd are repetitive; words are glued together with dashes:

"Do not enter first-first-first-first-first-first-first-first-first

Do not enter alone-alone-alone-alone-alone-alone,” etc.

p.21. The process of observation of little trivial things… the words representing things-movements-impressions stick to each other. Unconscious thoughts seem to stick together when we look around without much concentration. The words are tailing in a long zigzagging line.

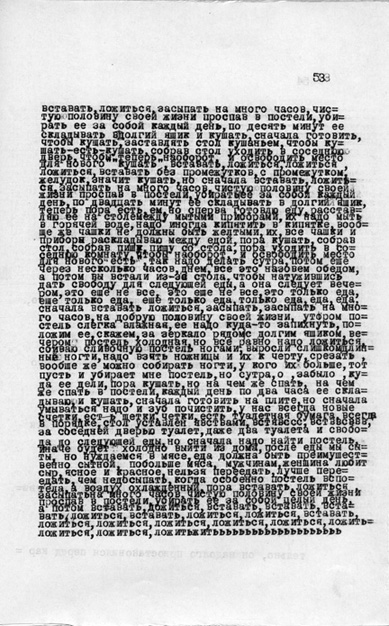

p.53. Compressed texture of a boring trivial life. It traces the monotone dynamics of social biology. If we condense that narration to its meaning it would come out like this: waking up, eating, going to work, back home, dinner, sleep, and so on and on. The last three lines of the text repeat the word “lie” (down to sleep). The text ends on the letter “ь“ called “soft sound“ which is soundless. Soft and silent, it adds the vapors of a soft soundless dream to that otherwise pressed down prosaic life.

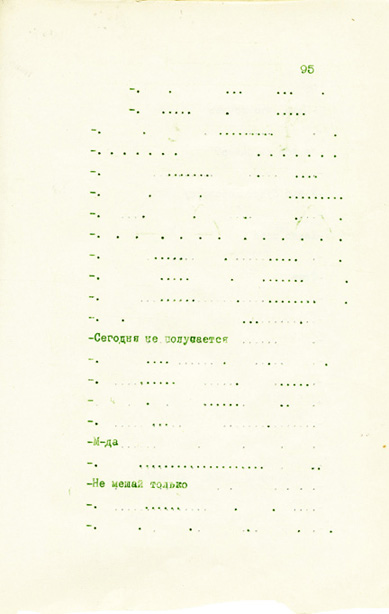

P.95. That is a part of the central polilogue lasting several pages. Typed through the green carbon paper, the stenographic text reflects word-by-word conversation, including hesitations, interjections, and mumbling.

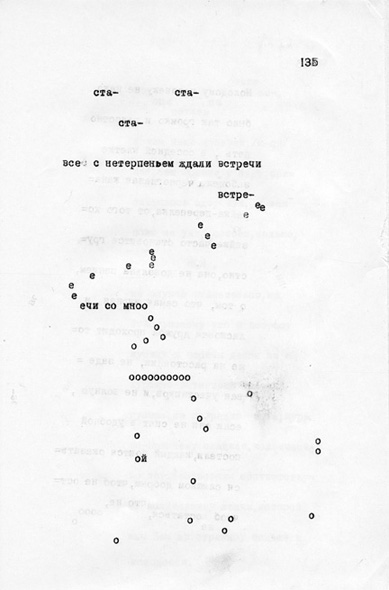

P.135. The words “waiting for me” are dissipated; the hovering vowels “e” and “o” express boredom of waiting. The bubbles of “o” are floating on the bottom of the page; “oi” (“ouch!”) is among them.

P.138. In the labyrinth of thinking while waiting for my dear husband. It starts from the brief reminiscence of some recent visitor and turns into intensive expectation. When the line spirals backwards the words are written backwards as well.

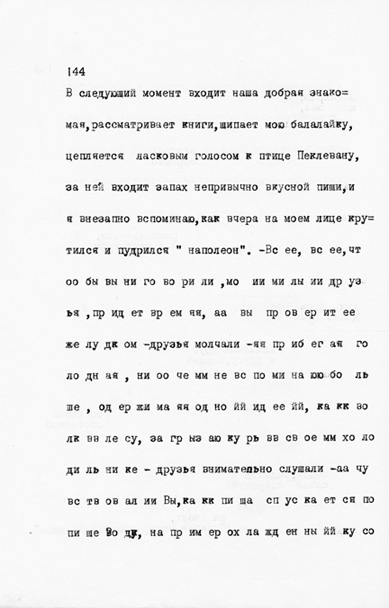

P. 144. The fluid synergetic sentence in which a division into words are simply skipped, instead there is staccato of two-letter units. People are breathing out syllables in a trivial conversation.

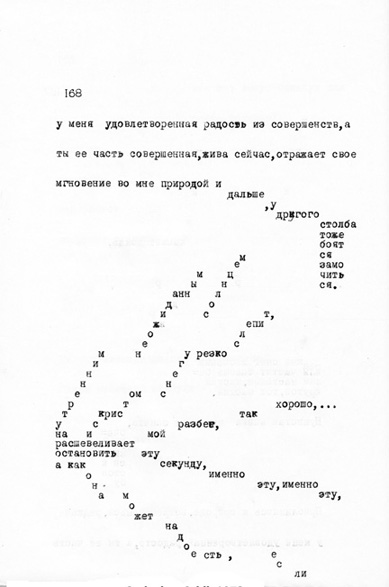

P.168. The morning sunrays show their trajectory on the snow. The bundle of light rays.

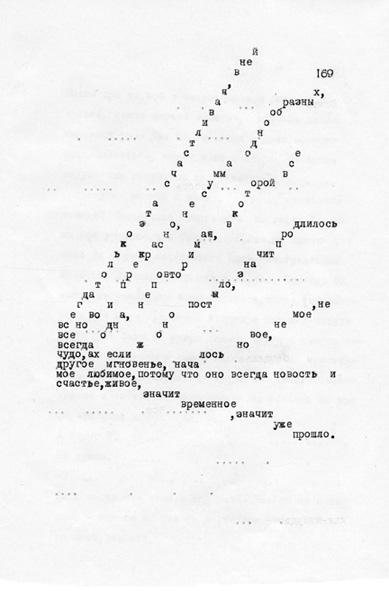

P.169. Sunrays, they “blind me”. There is a straight reference to the title. “Bli”..nd” me –“Sle”… pit.”

If we summarize the idea of these two raying texts, it will come to this:

Sunrays… my love…that is so beautiful moment, but if it is eternal, even it might bore. Faustian “Stop, Moment! You are so beautiful!” is hidden between the lines, or rather between the rays of words. Yet, these sunny rays and, in fact, the entire book are about love, howled down by many voices and expressed in many strange patterns of nature.

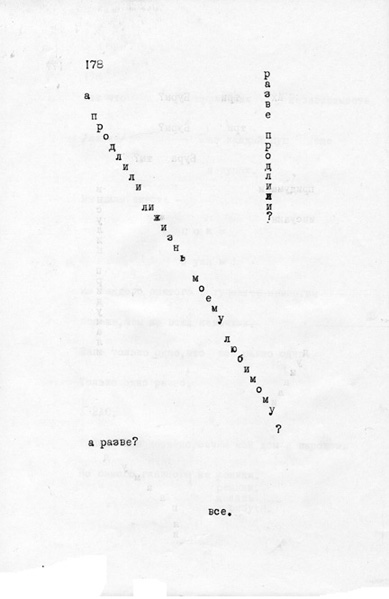

p. 178. The vertical question “Is the life of my lover prolonged?” is answered by the two horizontal one-word sentences are: “Is it so?” and “Vse,” meaning “that’s all.”

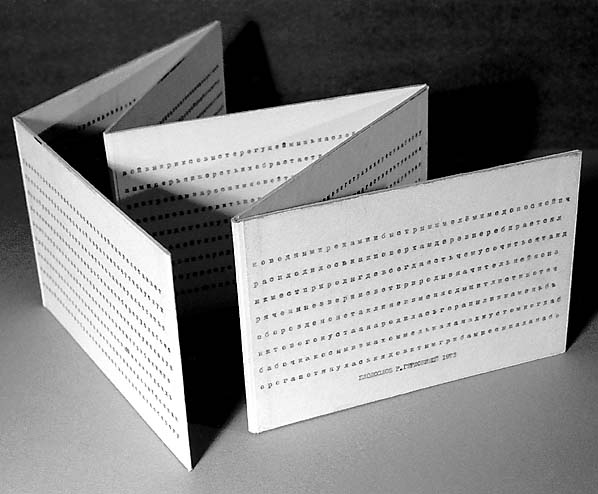

The next two poems Lamark (1973) and the folding book Wordspring (1973) are written literally in one word, being presented as one fluid synergetic sentence in which a division into words are simply skipped.

| Rimma Gerlovina, Lamark, 1973, carbon paper monoprints by Valeriy Gerlovin, hard binding, paper, typewritten text, 9½ x 15", 16 pp. |

Rimma Gerlovina, Wordspring, 1973, folding book, cardboard, typewritten text, 6 ¼ x 54 ½".

The high potential of a word is hidden not only in its meaning, but also in its visual envelope. Implying its shape shifting syncretism, it is possible to synthesize some sort of conceptual organon to communicate wholeness through incorporation of diversity, aligning the weird and wonderful chain of references between art, life, literature, mythology, religion, philosophy, and music. The word might be compared to the primal creative impulse; therefore, even in a canonical sense it was "in the beginning."

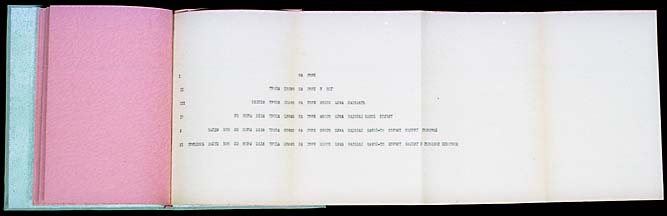

| Rimma Gerlovina, Singing for Irene, 1973, the pages from the score for three voices. Cradboard folder with 31 pp., each 9 ¾ x 13 ¾". |

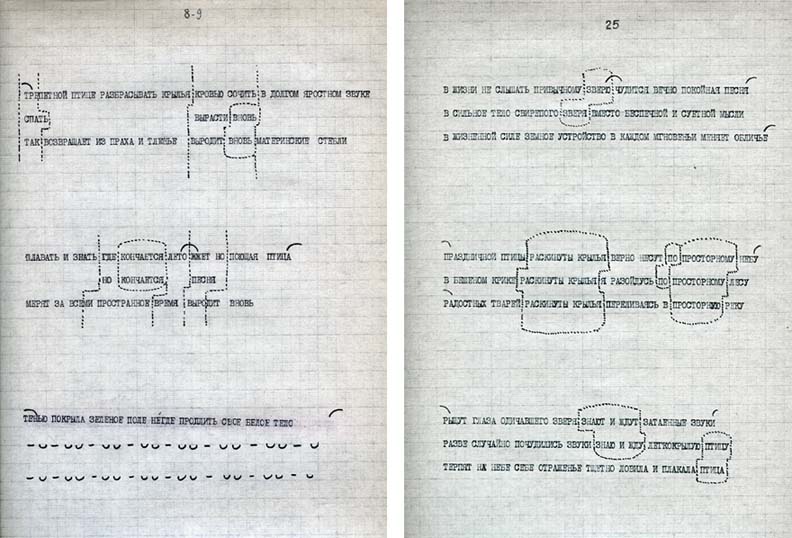

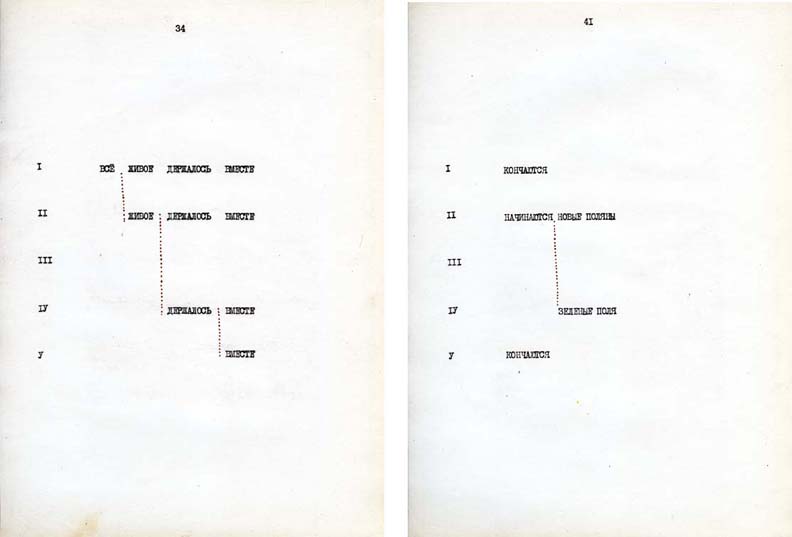

The next stage of poetic development brought with it the whole series of scores intended for simultaneous reading by several voices, arranged in a sort of spoken madrigals. In the polyphonic poems Singing for Irene and Thoughts about Irene (respectively for three and five voices) reading in unison alternates with slightly cacophonic separation of voices that expand as numbers into factors, for each voice has its own distinct part, being adjusted to all others.

| Rimma Gerlovina, Thoughts about Irene, 1973-4, two pages from the score for five voices. Cradboard folder 8 ¾ x 12 ½" with 64 pp. (Link to the text) |

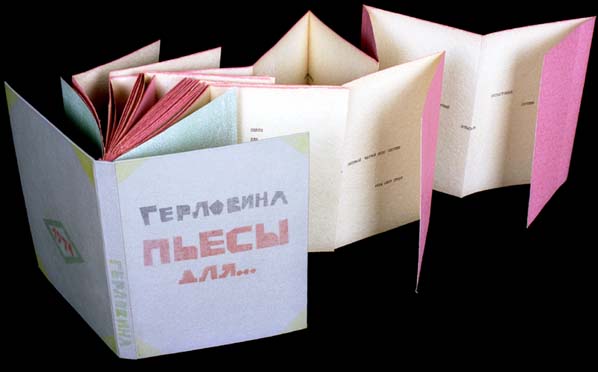

In the book Plays for Polyphonic Reading (1974), each poem is written on a separate unfolding page, like a brochure. Bounded together under the hard cover, they seem to comprise a kind of a literary community of rather independent members. The pages, some of them being longer than three feet, are cut out of pink wallpaper, the only monochrome long enough paper we managed to find in Moscow in those days.

Rimma Gerlovina, Plays

for Polyphonic Reading, 1974, hard binding with carbon paper monoprints

by Valeriy Gerlovin. The sizes of the unfolded pages vary from 11½ x

9½ to 48 ¾ x 9½", typewritten text, 37 folded pp. (Link

to the text.) |

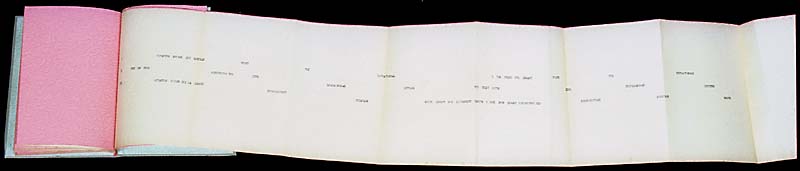

Folded separately, each poem keeps its distinctive features as in subject, so in form, written as waltz without words, arranged in a mountain of voices both visually and sonorously, or displayed as a minimalist landscape of words. An employment of different conceptual details in the poetics, and especially in the constructive shape of its "collective" binding, moves this book closer to the realm of interactive art objects, preparing it for a new genre of conceptual cubes.

Rimma Gerlovina, Plays

for Polyphonic Reading, 1974, the unfolded page with the poem The Mountain for six

voices. The sound of the poem grows and falls according to the

visual score. |

| Rimma Gerlovina, Plays for Polyphonic Reading, 1974, the unfolded page with the poem for three voices (Link to the text.) |

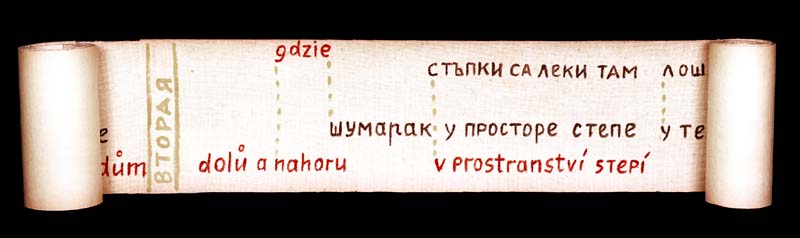

The polyphonic score Four Preludes before the Birth (1974) is written for a quintet of reciters in five Slavic languages: Russian, Bulgarian, Polish, Czech, and Serbian. At that moment it seemed to be natural to turn the subject of philological education (received at the Moscow State University in 1973) into a creative tool. That score reflects an echo of the protoslavic union in its morphologic and phonetic aspects, thus reverting words and their sounds towards their ancestral sources into one polyvalent monologue splitting into a choir of voices.

| Rimma Gerlovina, Four Preludes before the Birth, 1974, canvas on paper, acrylic, 157½ x 76" (Link to the full view of the scroll.) |

The visual and sound fusion of that language family produce an effect of shamanic chanting, proceeding on a background of some familiar words mixed with obscure morphemes. The meaning of the poem appears relatively clear, but not quite so. There is something hidden deep down in the genetic memory of each Slavic speaking person. The poem consists of four preludes; the fourth one being composed arbitrary, i.e., it has neither plot, nor form, but suggests an utter freedom in its interpretation. Four Preludes for the Birth was the last polyphonic score preceding the cubes characteristic with a new form of conceptual thinking with solar stability and intellectual stylistics.

Rimma Gerlovina, Four

Preludes before the Birth, 1974, at the exhibition Russian Samizdat Art at LACE (Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions) in 1984. In front cubic

organism One Man Show,1983. (Link to our article about the exhibition Russian

Samizdat Art) (Link to the full view of the

scroll.) |

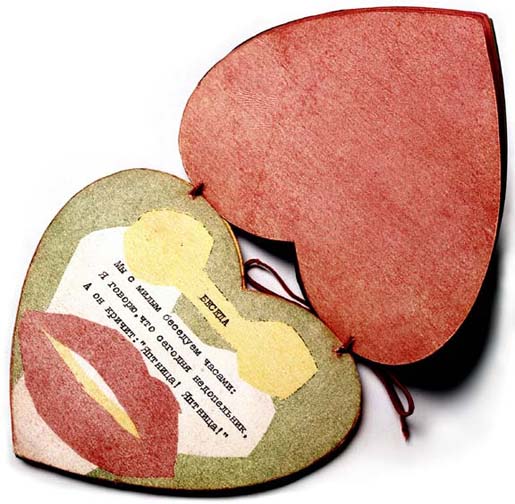

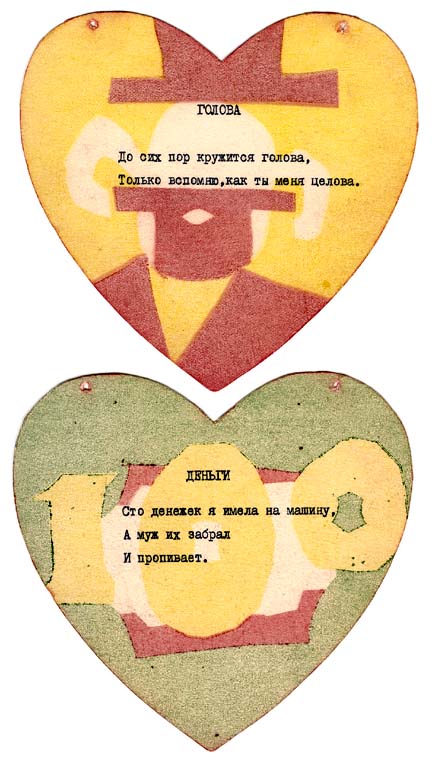

In the interim, together we made two books in Plexiglas covers, containing Rimma's absurdist verses and Valeriy's carbon paper monoprints. Two accidentally found plastic cutout forms, some obscure remnants of unidentified technical appliances, served us as a cover for the book in a shape of a tortoise. The next plexi-book was already hand cut in a shape of a heart, appropriately, bearing the title Love (1974).

Rimma

Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Love,

1974, green plexiglas cover, typewritten text, carbon paper

monoprints, 6 x 5¾", 10 pp., 2 versions, one

version is in the collection of The State Тretyakov Galler, Moscow, Russia. |

Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Love, 1974, two pages.

One of the poems in the Tortoise book (1973) plays on inversions and whimsical literary criticism, already touching some venues of our future linguistic and artistic environment in America, where we moved six years after writing these verses:

Villemel and Manwhit,

Tatins of Aremican rwiting,

Are crikstering and prolesyting.

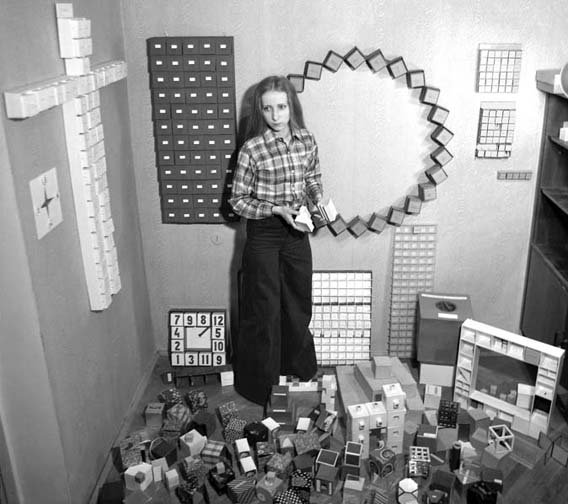

The search for the exact form seemed to be a way to enter into another dimension of conceptual poetry. In 1974, little cubes, the portable objects of three-dimensional poetry, burst forth as if a fountain, overflowing our entire apartment in Moscow.

Rimma Gerlovina with the cubes, 1976, Moscow

In 1975, the small boxes grew into the Cubes-Environments, the series of the projects, in which the spectator is turned into a performer. Upon entering each of these objects with different settings, one unintentionally follows its scenario. These works syncretize elements of diverse genres, entwining environmental art with conceptualism, dramaturgy and polyphonic poetry.The series opens with the two-meter side Mirror Cube, 1975, all interior sides of which are made of mirrors. Upon entering that cube, the spectator finds himself in the focus of all its six mirrors, astonished by enormous multiplication of his own reflection. The immersion into the environment with reverberating self-image is accompanied with the repercussive quadraphonic sound. The polyphonic poem is recited slowly, similarly to echo by an announcer whose voice preferably would have hypnotic qualities. The text is recorded by means of superimposition, producing a multi-voiced resounding. Here, one experiences the effect of audible and visual synchronization of the echo and the infinite corridor of reflections of the listener. One intermediate strophe from that sound poem might give a sense of its dominant rhythm, the unison of "I am" and dispersion of all other meanings. (Link to the original text)

1st voice: ............................................................................................................................................

2nd voice: ...........................................................................................................................................

3rd voice: I am continuation of life I am continuation of life I am continuation of life I am continuation of life

4th voice: I am pores I am ready I am here I am seeing I am hearing I am people I am sample I am number

5th voice: I am photo I am volt I am veto I am hundred I am spectrum I am litre I am meter I am point

The life of an artist usually has many twists and turns; in a way, it is a happening in itself. From the point of view of an ordinary person, it looks rather like a "mishappening," just as it does in the series of Cube-Environments. In some sense, psychoanalytic projects contain elements of visual poetry and more importantly, they are written with a sense of irony.

< home < content to The Cubes >