< home < content next: part 2 >

RIMMA GERLOVINA

THE CUBES

© 2010, Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin

PART 1

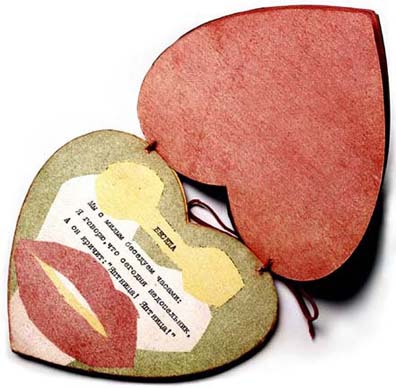

Before the cubes came into life, the experiments with visual prose and poetry preceded these sparks of conceptual imagination that appeared as flashes of an immediate experience "boxed" in the cubes.

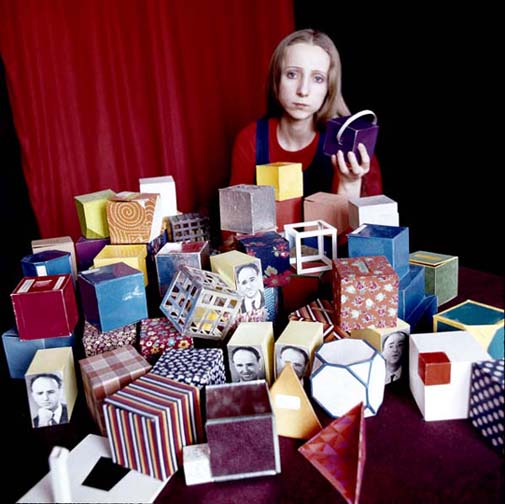

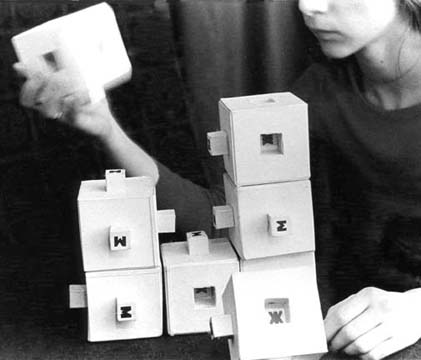

Rimma Gerlovina with the cubes 1974-6, Moscow, photo by Igor Makarevich.

In attempt to give a visual history of that hour, it may be mentioned that all early typewritten visual prose and poetry were written in different patterns and issued as handmade books. Almost all of them contain graphic works by Valeriy, to be precise, the monoprints made with the help of color carbon paper. (Link to "Visual and Polyphonic Poetry")

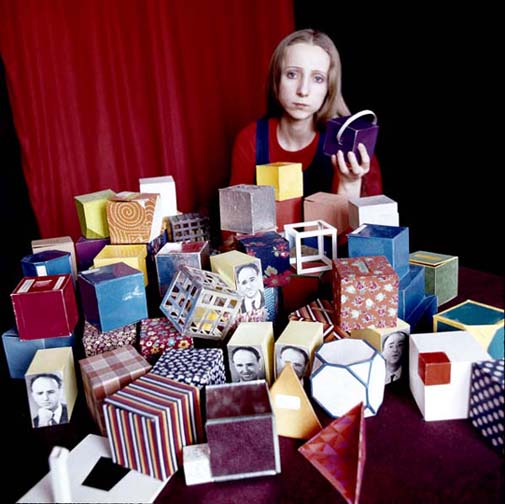

Rimma Gerlovina, Plays

for Polyphonic Reading, 1974, hard binding with carbon paper monoprints

by Valeriy Gerlovin. The pages are folded inside the book,their sizes vary from

11½ x 9½" to 48 ¾ x 9½", typewritten text, 37 pp. (Link to the original text.) |

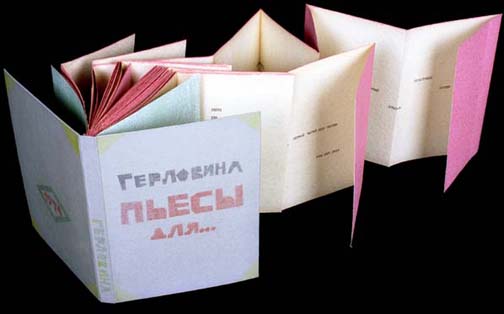

Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Love,

1974, green plexiglas cover, typewritten text, carbon paper

monoprints, 6 x 5¾", 10 pp., 2 versions, the

first version is in the collection of The State Тretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia. (Link

to "Visual and Polyphonic Poetry") |

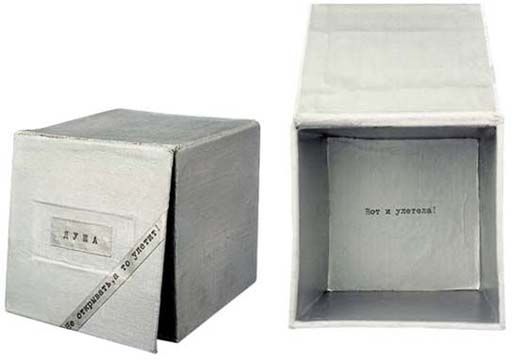

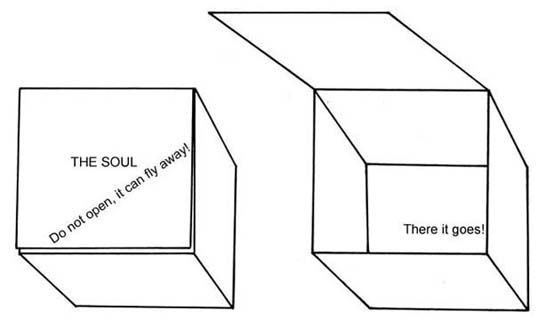

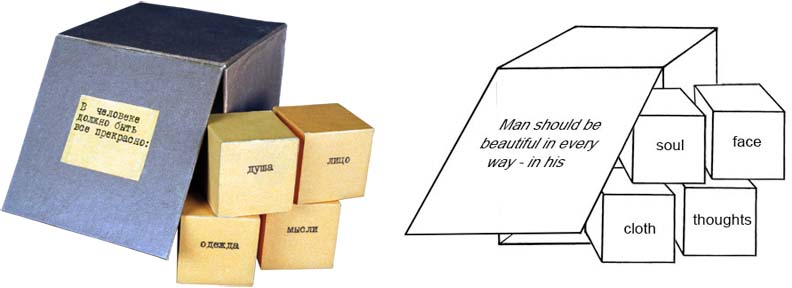

The search for the exact form seemed to be a way to enter into another dimension of conceptual poetry. In 1974, little cubes, the portable objects of three-dimensional poetry, burst forth as if a fountain, overflowing our entire apartment in Moscow. Made with one breath, they were given away as gifts to our friends, artists, and poets, with easiness and spontaneity. Cubic concepts are embodied in different geometrical forms; in general, they are clothed in cardboard cubes, each 8 x 8 x 8 cm (3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼"), featuring inscriptions inside and outside. Many of them are occupied by little wooden cubes, 3 x 3 x 3 cm (1¼ x 1¼ x 1¼" ), also with a short conceptual message. Serving as allegorical units of time, space, or human character, they are specimens of a noetic form of concrete poetry that gains new corporeal habitation in the cubes. For example, upon opening the cube that says on its lid "The Soul. Do not open - it can fly away!," one sees the message written on its bottom, "There it goes!" (1974).

Rimma Gerlovina, The Soul, 1974,

cardboard, paper, fabric, acrylic, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼".This cube and many others are in the Collection of The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia; The Getty Research Institute, Jean Brown Collection, Los Angeles, CA; and Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers State University, New Brunswick, NJ. |

Collection Centre Pompidou (Cubes) (Mirror Game) (2x2=4) (Ursa Major)

In mythology, thetruth was always veiled by parables and images in order to preserve it from an unprepared eye, which tends to distort it. With some kind of ironic twist, the lid of that cube "covers" the age-old secret, as if with an aesthetic veil preventing it from misinterpretation. As soon as man tries to grasp the idea logically, its essence is diluted. The uttered thought reflects the truth only partly, especially in such a delicate case; therefore, any curious eye meets the predictable result, "There it goes!"

| Rimma Gerlovina, A Naked, 1974, cardboard, paper, fabric, wood, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼" or 8 x 8 x 8 cm. |

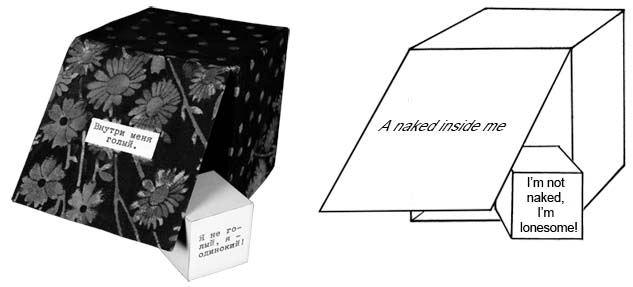

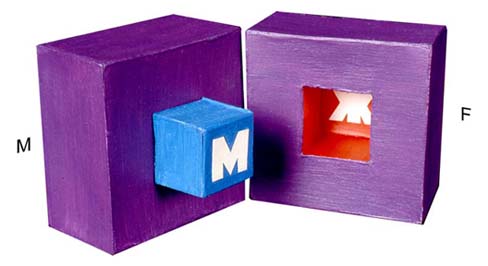

Rimma Gerlovina, M-F,

the half with the blue convex "M" that stands for "male" can be united with the

red concave "F" (female). Folded together, the cube

represents the androgynous unit; its purple color is a combination of red and

blue. 1974, cardboard, paper, acrylic, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼".

Collection of the Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig, Vienna, Austria. |

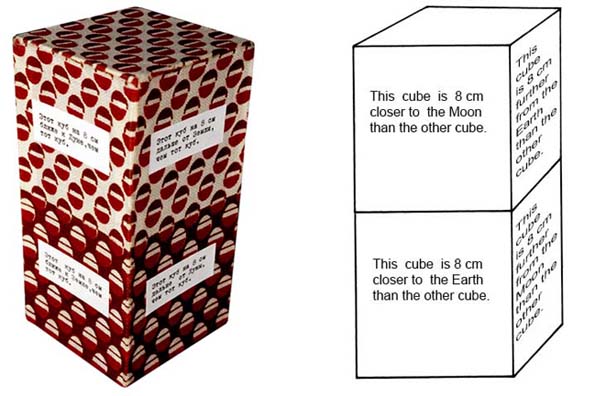

| Rimma Gerlovina, Moon–Earth,1974, cardboard, fabric 3¼ x 3¼ x 6½" or 8 x 8 x 16 cm. |

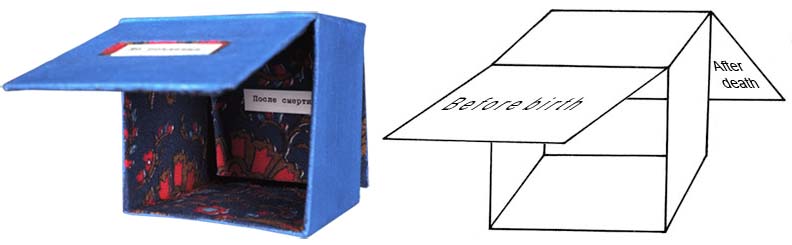

| Rimma Gerlovina, Before Birth - After Death: The cube can be opened from two sides; "Before birth" is written on the lid, "After death" appears on the bottom side, 1974, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼". |

Being on the border between art and poetry, these cubes are like materialized haiku speaking in a language of coded simplicity. Precisely that paradoxical simplicity in combination with an analytical approach, lyrical irony, and a fatalistic element organize, so to speak, the semantic environment of the cubic organisms. At the same time, its metaphoric impact does not inhibit a possibility of polyvalent interpretation of the cubes. In them, to put it allegorically, "drops" of Aesopian thoughts wear away the Sisyphean stone. The characters of these homo-cubes (especially those which talk as dramatis personae) are symbolically revealed as if in an anatomy theater: not nude, but naked.

Perhaps, it was not an accident that the cube Quintessence appears first, while logically should be the last one (1974). It seems to contain the beginning and the ending simultaneously.

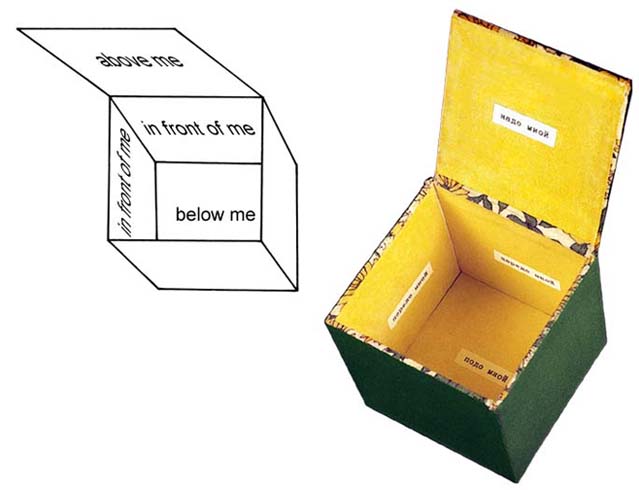

| Rimma Gerlovina, Quintessence,1974, cardboard, paper, fabric, acrylic, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼". |

Traditionally, the solid body of a cube has been used as a symbol for the material substance of the world, which is precisely the place where the hidden creative force operates. In this literally three-dimensional poem we hear only the voice in the first person that determines its location in space: as "above me," so "below me," repeating "in front of me" four times, like an invocation. This voice is articulated not by the tongue but by the projected inscriptions located respectively on each surrounding wall of that cubic space. But the entity to which this voice belongs is invisible. Akin to the four space orientations marked inside this cube (left, right, above, and below), four elements constitute our material universe in mythological terms. Traditionally known as the elements of fire, water, air, and earth, in certain combinations they can bring into existence the fifth element, the quintessence of the other four, represented by aether. The first four are "squeezed" like a lemon into the fifth invisible one, which is the most potent and ultimate of them all. Symbolically hidden inside the material factor (exemplified by this poetic cube) the fifth element operates in a manner of an Aeolian harp. The source of its sound is hidden in its self-sufficient nature, without an assistance of a player, when a harp is merely brushed by a wind. Clearly projecting its location, the voice becomes a witness of another intangible dimension right in the middle of the tangible sides of the cube. In a poetic sense, the quintessence is the voice of consciousness that a priori knows the mystery of time and space, in which we all are set like in that cube.

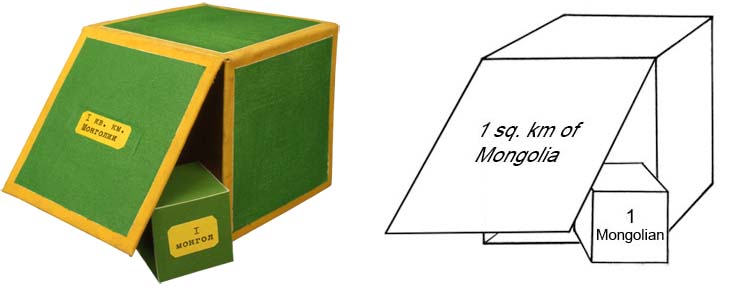

| Rimma Gerlovina, A Mongolian, 1974, cardboard, paper, fabric, wood, acrylic, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼". |

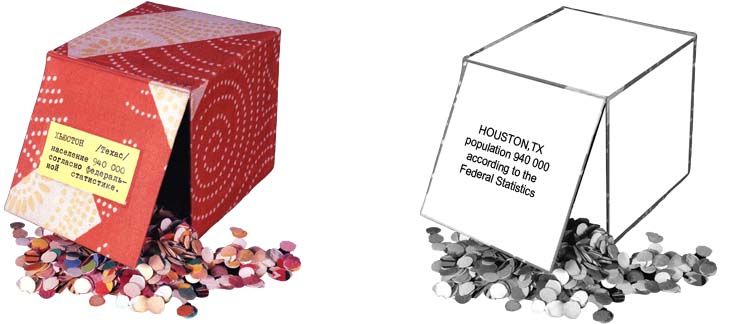

Not only metaphorical puzzles, but also facts and actual pieces of information might be found in those boxes, which present mundane matters with ironic evidence. For instance, the cube with geographical titled 1 sq km of Mongolia (1974) has a small population density: only one little cube identified, as "1 Mongol" inhabits its territory. That simple statistical data taught in our school days has engraved itself upon our memory due to its elegant proportionality. In the same line, the cube with the label Houston,TX, population 940 000 according to the federal statistics (1974) is entirely filled with confetti.

| Rimma Gerlovina, Houston, TX, 1974, cardboard, paper, fabric, confetti, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼". |

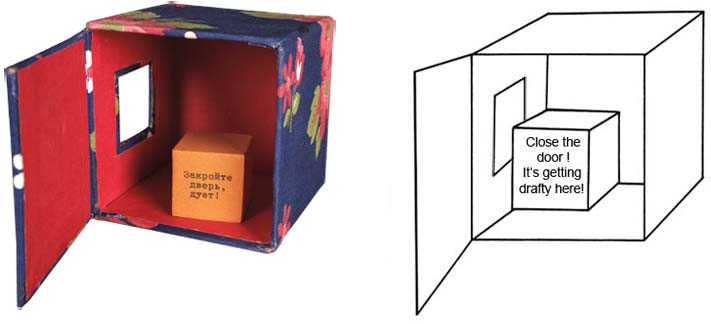

| Rimma Gerlovina, Draft, 1975, cardboard, paper, fabric, wood, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼". |

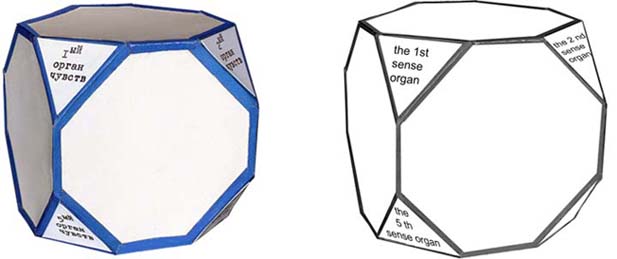

| Rimma Gerlovina, Eight Sense Organs: "the 1st sense organ," "the 2nd sense organ," etc. is written on each slanted corner. 1974, cardboard, paper, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼". |

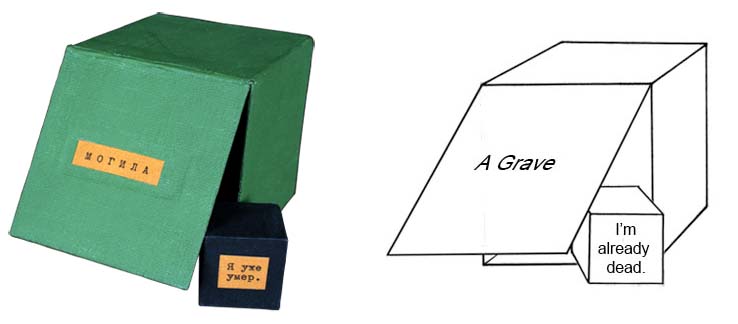

| Rimma Gerlovina, Grave, 1974, cardboard, paper, fabric, wood, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼". |

Many cubes can be opened and taken apart, while others can be arranged into composite objects, like The Face of the Politburo (1975) consisting of nine cubes. Each side has a fragment of the portrait of one of the six leading members of the Soviet Politburo. Turning over the cubes, one can create an archetypal face of a Soviet party leader. Indulging in that frivolous creativity, many of our friends chuckled at the characteristic features of well known faces - Brezhnev's bushy eyebrows, or the thin compressed lips of comrade Suslov - but as it has been known long ago, changing the order of parts does not change the end result of the commutative property of addition.

| Rimma Gerlovina, Face of the Politburo, 1975, collages, wood, cardboard, fabric, 5¾ x 5¾ x 2", collection of The Centre Pompidou, Paris (link to the work in the collection) |

The mutable object called Group Sex (1975) also can be freely composed of its individual units: the male cubes with convex additions and their female concave partners. The actual shape shifting forms of that object, whether a tower, a zigzag, or a flat wall, depend on a fantasy of its manipulator.

Rimma Gerlovina, Group

Sex, free composition assembled with the help of convex "M" cubes and

concave "F" cubes, 1975, cardboard, paper, each M-cube is 3¼ x 3¼

x 4½ ", F-cube 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼". Photo by Victor

Novatsky. Collection of The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow |

Two larger cubes called Art Sets (1975) are filled with 64 small wooden cubes bearing real artists' names; one of these sets is international, not limited by time frame and locality, the other is a strictly Russian collection of non-conformists artists of the early 1970s. Their instructions suggest strategies for rearranging the artists-cubes according to any desirable criteria: by art, importance, material possessions, age, beauty, or simply by personal preference. Both Art Sets include one unlabeled cube, reserved for an artist, whose name is not yet inscribed in the history of arts.

| Rimma Gerlovina, International Art Set: 64 cubes with names of different artists. 1975, wood, paper, cardboard, ink drawings, 5¼ x 5¼ x 5¼", each cube 1¼ x 1¼ x 1¼". |

The cubic wall poem Three Generation (1975) traces monotone dynamics of "social biology," i.e., it illustrates "man-units" with a vegetative form of thinking. In parallel, Valeriy also explores the similar theme of faceless power of instinct ruling the collective unconscious. His natural inferences materialized in the wide-ranging series, Collection of Natural History Museum (1976).

| Rimma Gerlovina, Three Generation: Different full names are inscribed on the front side of each cube, while the other sides read as follow: "was born," "has breakfast," "has lunch," "has dinner," "died." Each family is denoted by one color. 1975, wood, cardboard, paper, 15¾ x 3½ x 1¼". Collection of The State Ttertyakov gallery, Moscow. |

The latent principles inherent in the nature of all beings predominate if the mind operates only within generic thinking and tends to seek only this world, to amass a fortune and leave the overflow to the progeny. The average man wants to be like everybody else, only more successful than others; therefore, while laying claims on individualization, he agonizes at the first attempts of coming closer to it. As Herman Hesse noticed, "There's an immense difference between simply carrying the world within us and being aware of it."1 Giving supremacy of the lower values over the higher ones, the humanity perplexed in that inversion even more now - to paraphrase it poetically, the soul is supposed to be a master of the body - but presently, the latter seems to overmaster itsmaster.

| Rimma Gerlovina, After Chekov, 1974, cardboard, paper, fabric, wood, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼". |

--------------------

1/ Herman Hesse, Damian, Siddhartha and Other Writing, (Continuum, NY, 1992), p. 177.

< home < content next: part 2 >