< home < content next: part 3 >

RIMMA GERLOVINA

THE CUBES

© 2010, Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin

PART 2

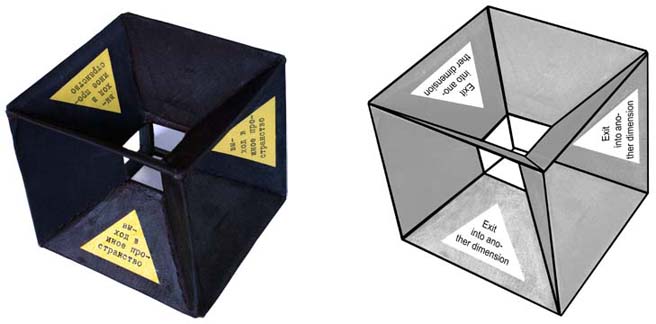

Talking in many voices, cubic entities that populated these metaphorical objects suggest different concepts. Their peculiarity is not only in their unusual expression; they seem to have a gift for communicating abstruse arguments to intelligent laymen. Some concepts used to provoke intellectual discussions such as the cube Exit into Other Dimension (1975) that looks like an intuitional model of "tetraspace."

Rimma

Gerlovina, Exit into another Dimension: "Exit into another dimension" is written on each side, while all sides lead to one central hole. 1974, cardboard,

paper, fabric, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼". |

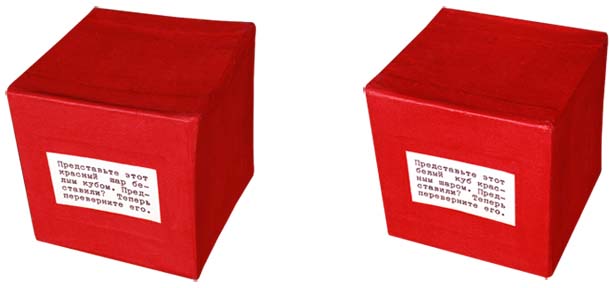

Hinting at another ordinarily inaccessible exit, each side of the cube bears the same direction. However, each of them leads to the same central gap that unites all these planes, pointing to the door that is perpetually open but hard to find. As to the artistic way of seeing certain superior arrangements, their set-up is symbolically conceptualized in this cube as the model of interrelation of macro- and microstructures. Is it a visual joke or mini-architecture of would-be polymorph exit into other dimension? It might be both a rabbit hole for Alice and an artistic version of the intergalactic Einstein-Rosen Bridge. Theoretically, it depicts how the vital forces of the world are sublimated into their invisible center - into their quintessence, exactly as it was projected in the very first cube with the same title. If the idea was expressed subjectively in the first version, one can see the entirely objective presentation of the quintessence in this black hypercube. Perhaps, this central unifying point that conjuncts the other four planes is never empty for a moment. On the contrary, it is always full and indicates the eternal presence of the spirit, which always exists everywhere and has no parts missing. Who can be sure that such zero point is not dangerous? It rests in the sublime indivisible center. To find it, the consciousness has to go through "the ceiling" of our 3-dimensional thinking, while the intuition has to make a knight's move. Perhaps, some cubes might prepare the filed for yet another source of aberrant ideas, as the Red Ball in a Shape of White Cube (1974) is prone to. The conceptualization of the imagination provokes irrational propositions that might be quite useful for the intellectual training and growing capacities of conscious intuition.

Rimma Gerlovina, Red Ball: "Imagine that red ball as

a white cube. Have you? Now, turn it over!" is written on one side, while on

the other: "Imagine that white cube as a red ball. Have you? Now, turn it

over!" 1974, cardboard, paper, fabric, acrylic, 3¼ x 3¼ x

3¼". |

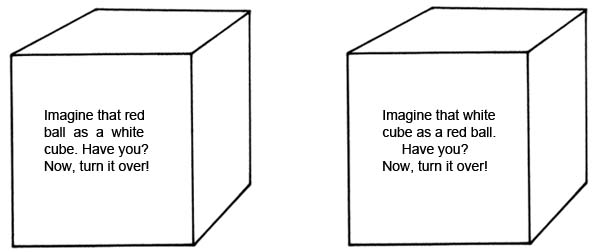

| Rimma Gerlovina, Cornered, 1974, cardboard, paper, fabric, acrylic, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼". |

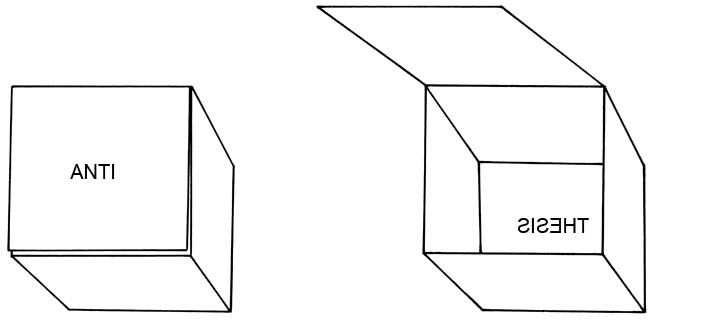

Rimma Gerlovina, Antithesis, 2008.

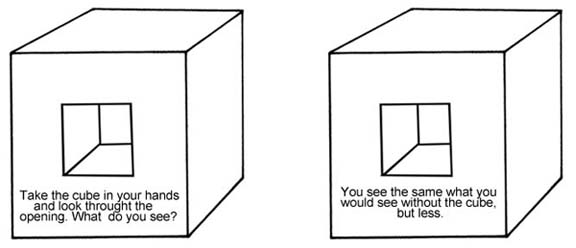

Rimma Gerlovina, An Opening: "Take the cube in your

hands and look through the opening. What do you see?" is written on one side,

while on the other: "You see the same what you would see without the cube, but

less." 1974, cardboard, paper, fabric, acrylic, 3¼ x 3¼ x

3¼". |

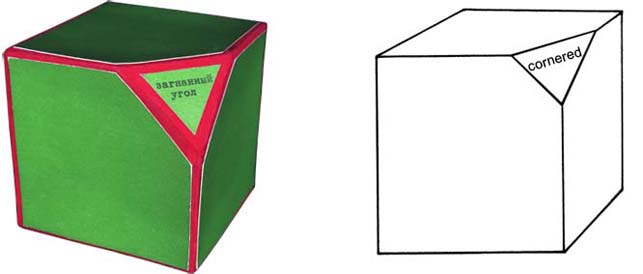

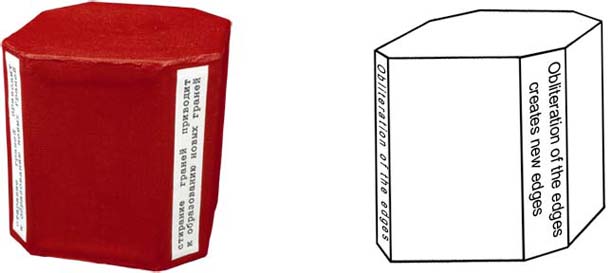

The lyrical message prompts not only reading, but also literally a psychosomatic examination of these solid bodies: to open and turn them over, look through their holes or to arrange them in different compositions. The contact between the spectator and the tactile object is much more intimate than it is possible in art or in writing, which is the hybrid of what these cubic concepts exemplify. The scientists, who frequently came to our apartment as in a gallery, were naturally inclined towards intellectualization of the cubes. One of the discussions stands in a memory, concerning the geometrical proof of the illogicality of the Soviet slogan that read, "Obliteration of edges between town and village." In the cubic language, it is presented in a theoretical way - "Obliteration of the edges creates new edges" is what is written on each cut-off rib of the red cube (1974). There is a second sense in that dilemma that concerns also another abstract problem of squaring the circle, which by itself is not without a paradox.

Rimma Gerlovina, Obliteration

of the Edges: "Obliteration of the edges creates new edges" is written

on each slanted edge. 1974, cardboard, paper, fabric, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼". |

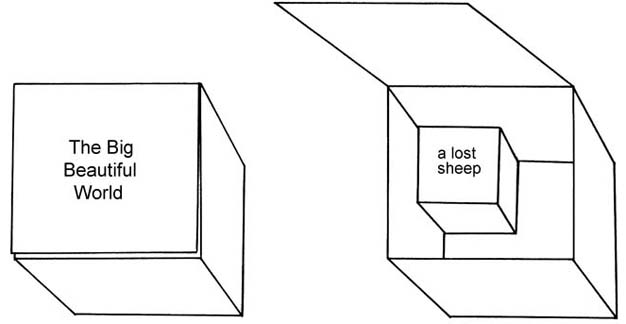

Rimma Gerlovina, A Lost Sheep, 2008.

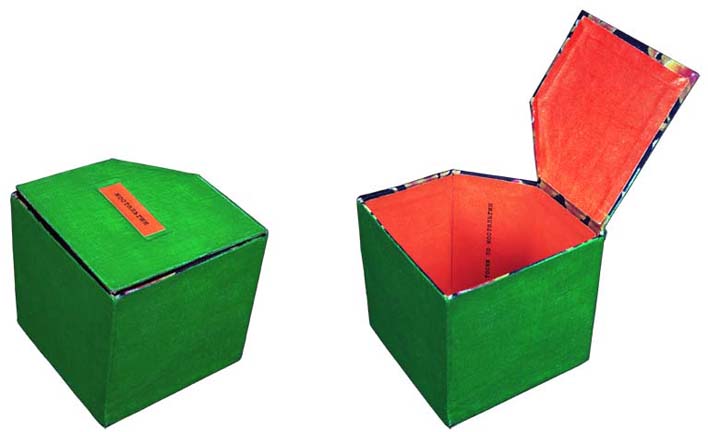

Rimma Gerlovina, Nostalgia:

"Nostalgia" is written on the lid, "Longing for nostalgia" appears on the

slanted edge inside, 1975, cardboard, paper, fabric, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼". |

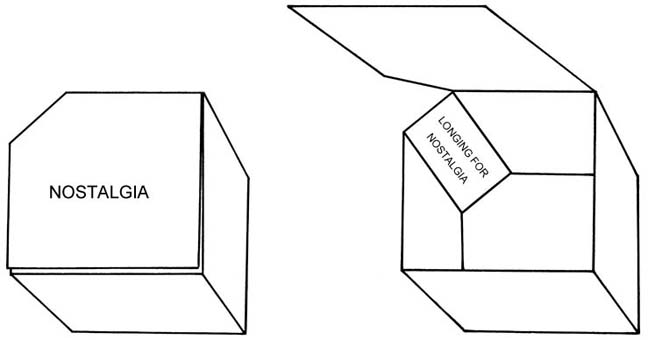

If the cubes provoked tendency towards thinking and intellectualization in some spectators, others accepted them with witty enthusiasm or a light sense of humor. For instance, Vsevolod Nekrasov, one of today's best contemporary poets, used to call his 24-years old college the "grandma of Russian conceptualism." His friend painter, Eric Bulatov, made a pencil portrait of that "grandma" as a gift to our departure from Russia. Greeting us already in New York, sotsartists Komar and Melamid personified their attitude in Artforum (March 1980) with a sympathetic irony:"The only woman in contemporary Russian Modernism exhibits a profound inventiveness in designing a wardrobe for her soul." Our frequent guest poet, Genrich Sapgir, once spontaneously versified his psychological observation: "Yourself as her cubes, she multiplies." One of his poems, Man Is Killed Over There (1976), was reset into cubic shape, which Genrich took home along.

Rimma Gerlovina, Man Is Killed Over There! (after Genrich Sapgir), 1976, cardboard, paper, wood, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼".

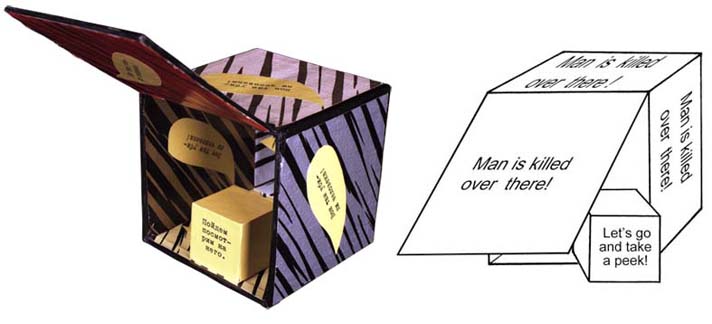

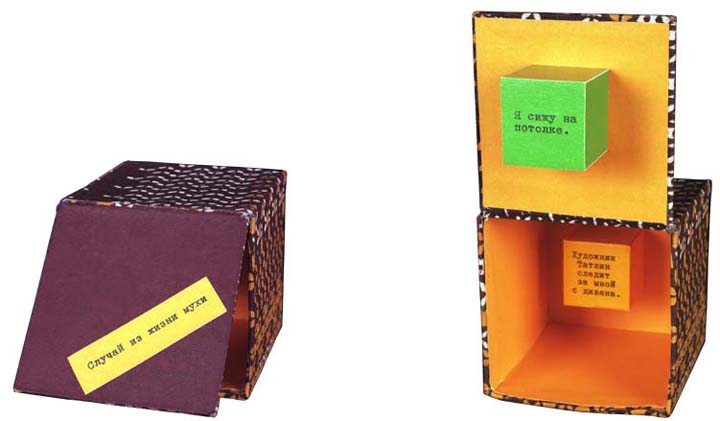

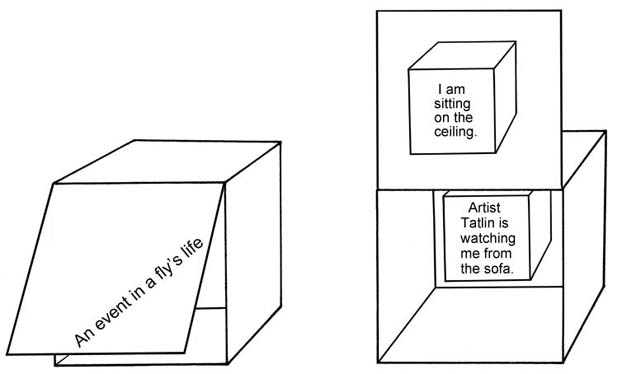

In the cubes, the "borrowed" strophes took rather an inverted form: the thoughts were not "unwinding" into the words, but the words were condensed back into the thoughts, filling up the rest of the space with the silence. The cube, An Event from the Life of a Fly, appeared in two versions: one such event in its short life is related to artist Vladimir Tatlin, while the other is linked to Ilya Kabakov (1976). That cube seems to attract the image of Kabakov "by itself," since there are many flies depicted in his artwork, which could infer the existence of an entomological relationship between the artists and their subjects of interest.

Rimma Gerlovina, An

Event in a Fly's Life: "I am sitting on the ceiling." is written on the

cube attached to the lid inside and on the small cube on the bottom: "Artist

Tatlin is watching me from the sofa." 1976, cardboard, paper, wood, fabric,

3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼". |

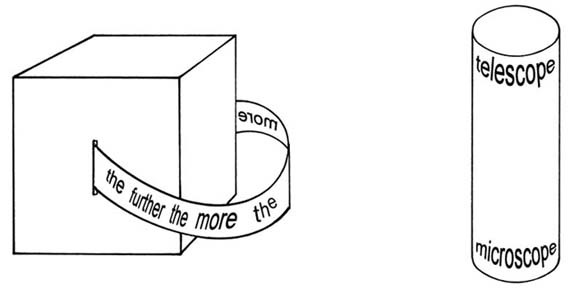

Rimma Gerlovina (left) The

Further the More: that text is repeated all over the strip. 1975,

original version cardboard, paper, wood, fabric, 3¼ x 3¼ x

3¼" with the paper strip. (Right) Telescope - Microscope, 1975,

original version cardboard, paper, 6 x 2 x 2". |

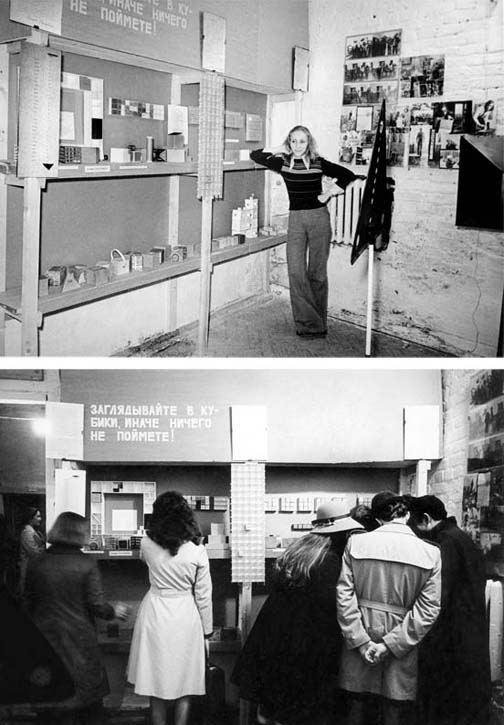

Rimma Gerlovina, an unofficial exhibition, 1976, Moscow

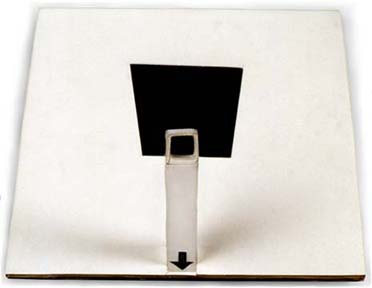

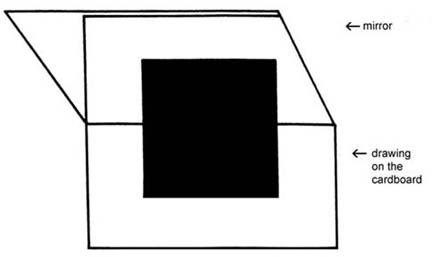

Small series of minimalist constructivist objects pays homage to Russian suprematism in a peculiar way. The illusory black squares on a white background are made out of the parallelograms, the trapezoids, and even the cubes; they, demonstrate how the geometrical rules can be contradicted optically, as in The Tool for Viewing Malevich's Black Square (1975).

Rimma Gerlovina, The

Tool for Viewing Malevich's Black Square: If one looks through the

small square hole at the black trapezoid, the optical illusion makes it appears

as a black square. 1975, cardboard, paper, 6 x 6 x 3½". |

Rimma Gerlovina, Black Square, 1975, cardboard, paper, wood, fabric, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼".

The other Black Square (which is actually a black cube) contains its own white "background" within. The exterior is switched with the interior, while the "flat land" of the square grows into a volume. Thus, the cube opens as a suprematist's casket, in which whiteness is equal to emptiness.

Rimma

Gerlovina, Black Square on White Background: A quadrilateral rectangle appears as a square when reflected in the

perpendicular mirror. 1976, in the

original version: mirror, cardboard, paper, 3¼ x 3¼ x 1½". |

One more Mirror Black Square is in reality only a half of it, while the other half is composed of its reflection in the attached looking glass. These geometrical "mishaps" of the black square echo the social theories of the Russian Avant-garde movement and the doubting of "victory over the Sun." All those political, spiritual, and aesthetic innovations seen by the exalted eye of Russian imagination had an optimistic popularizing character in time of the revolution, while changing into the monotone conservatism with the growing repression. Soviet socialism has developed in two opposite directions simultaneously: towards emancipation and towards the infringement of human rights. As Dostoyevsky predicted, "the most horrid crimes against the freedom" are committed "for the sake" of the freedom. At the beginning of each cycle of the formation of new social ideas, the creative innovators usually function in harmony with the developing line, whereas in time of their disintegration, they are replaced by the derivative newcomers, conservators, and simple charlatans. The archetypal structure of the beginning, the middle, and the end might be equally applied to the Russian Avant-Garde movement and Russian conceptualism, which in its turn, as one can expect, gradually degenerated into tautological reinterpretations of the works of the pioneers. Under supremacy of the established authorities, it grew into some sort of a mausoleum holding reservations for hot-sellers and connections.

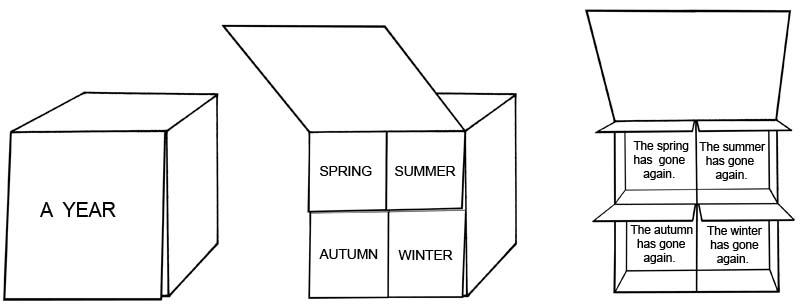

Rimma Gerlovina, A Year, 1975, cardboard, paper, wood, fabric, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼".

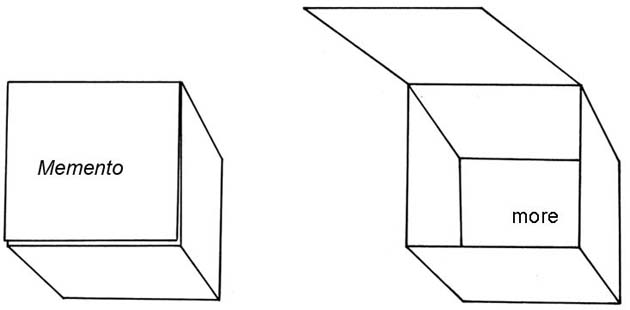

Rimma Gerlovina, Memento More: In the phrase "Memento mori" (remember

your mortality), Latin "mori" is

changed to English "more," 2008. |