< home < content next: part 4 >

RIMMA GERLOVINA

THE CUBES

© 2010, Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin

PART 3

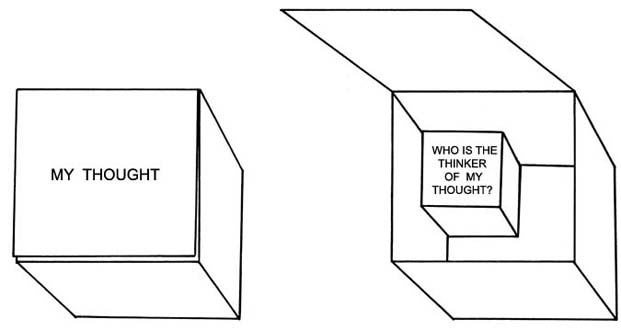

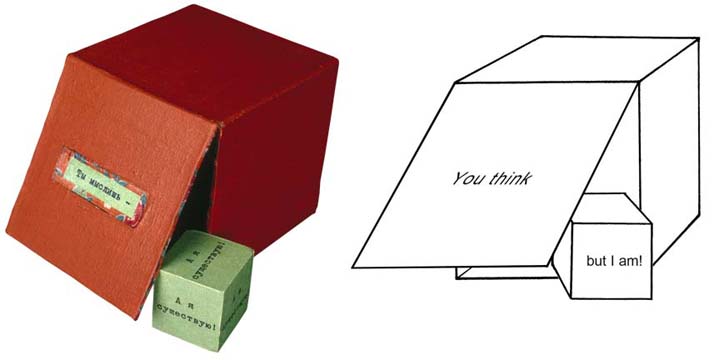

Couple of words might be said about the principle of interaction with these 3D concepts that often provoke the spectators' abilities for postulating and doubting. First, reason would step in and for the most part would overcome the feelings; but the irrational element implicit in the design of these concepts leads sophistry into a trap. A surface mental knowledge of things is an imperfect guide in dealing with these funny boxes, which seem to adhere to such modes of being that are strange in ordinary terms. If one opens the cube containing "my thought" on the lid, what would be the answer to its interior question? - "Who is the thinker of my thought?"

Rimma Gerlovina, My Thought, 2006.

Rimma Gerlovina, Black-and-White Hole, 1976, cardboard, paper, fabric, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼".

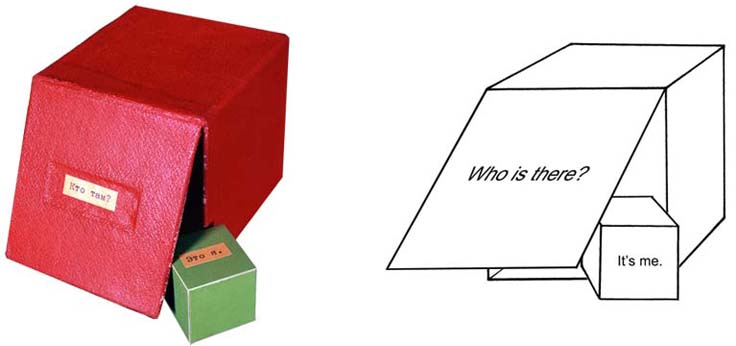

Rimma Gerlovina, Who Is There? 1974, cardboard, paper, fabric, wood, acrylic, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼".

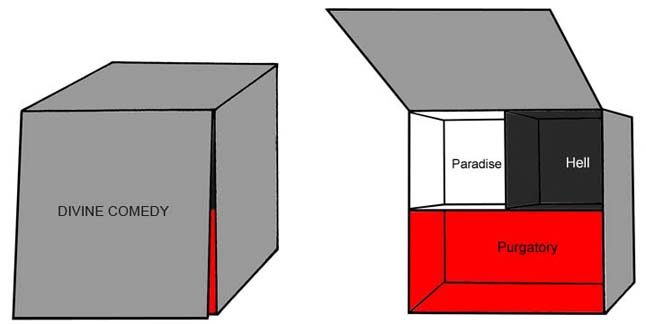

Rimma Gerlovina, Divine Comedy, 1976, cardboard, paper, fabric, acrylic, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼".

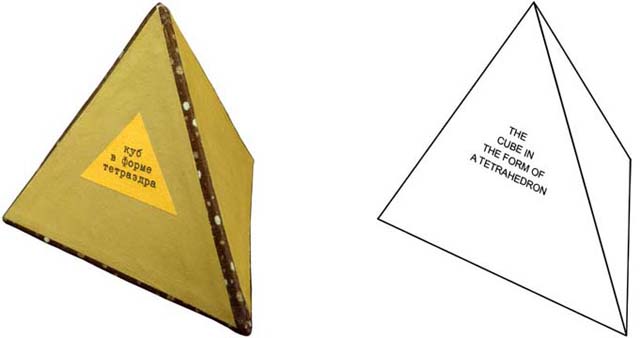

Layers of metaphors upon metaphors might be squeezed into a couple of words, shortening the exposition to a three-dimensional formula. For example, The Cube in the Form of a Tetrahedron (1974) questions the notion of human perception, as it, doubts man's closed-circuit ability to monitor life in its true essence.

Rimma Gerlovina, The Cube in the Form of a Tetrahedron. 1974, cardboard, paper fabric, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼".

Analogical concept is found in the cube, You Think - But I Am (1974), which first appeared in Latin language, illustrious with its minimum means for maximum effects. Here, Descartes' axiom "cogito, ergo sum" was converted into "cogitas, ego sum," while in the later version, "I think therefore I am" was paraphrased into "You think" (inscribed on the larger cube,) - "but I am" (on the small cube inside.)

Rimma Gerlovina, You Think but I Am, 1974, cardboard, paper, fabric, acrylic, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼".

Presented in a cubical form, the idea brings another twist to its meaning. Does human finite rationality have the power to transcend human finitude? Mind is always in a state of flux and yet wants to be a measure of all things. With logically coherent metaphysical structure, one can hope to understand everything in nature, but not nature itself. It seems that genuinely clear thought can objectify itself in spontaneous understanding only if intellectual contortions are subdued by intuitive simplicity; and that is not a new, learned tool, but an awakened a priori part of our consciousness, our refreshed genetic memory.

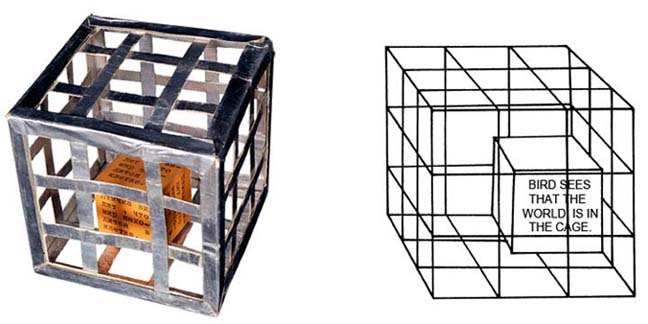

Some cubes were only a theoretical preamble for understanding, independent but related to many events that have yet to happen. Life has countless layers of forms veiling much deeper layers of ideas that might be approached through a grand interplay of intuition and playfulness. In reality, there are many hindrances, traps, and cages, metaphors of which are encapsulated in some of the cubes. The Bird in the Cage (1974) is one of the concepts illustrating a mental trap.

Rimma Gerlovina, The

Bird Sees That the World is in the Cage appears on the smaller cube

inside. 1974, cardboard, wood, paper, foil, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼". |

Sitting inside its silver cage, the yellow bird sees that the world is in the cage. People wrestle with the contradictions on the subjective side no less than on the objective one. Each person creates his own universe out of his own neurological processes, and the rest of the world looks at him with its collective eyes. In general, society consists of countless units, cages, and compartments in the manner of the honeycomb. Any social beehive keeps its honey supply for its own bees, for those who contribute and depend; that is why for the less-evolved types, any form of established structure serves as a saving power "from above." For those whose inner world is already rich enough, the same organization represents a binding and limiting force "from below." Our terra mater feeds and oppresses at the same time. Human intelligence is related to the plane of matter as its environment and support; therefore, all cages are different in accordance with the peculiarities of the psychological dispositions of their inhabitants. If one is not to merge into some sort of engulfing collectivity, the customary way of thinking must be reinterpreted. The bird might see the world in the cage because a wise man is always in some sort of enclosure "woven" by the folly and mental limitations of others. Loosening the bars of the gross material cage, the brain is able to create a sophisticated confinement for the intellect, acknowledging that the power of reasoning is not equal to the power of knowledge. At the same time, the surrounding world does not only exist independently from us, but it is also a result of our consciousness. Sometimes, external events are part of our destiny, as well as a part of our own temperament.

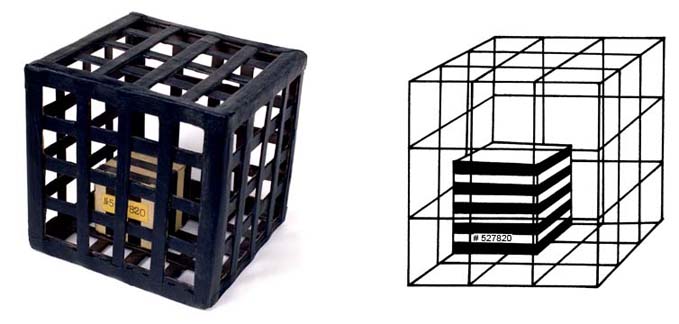

Rimma Gerlovina Convict, 1974, cardboard, wood, paper, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼".

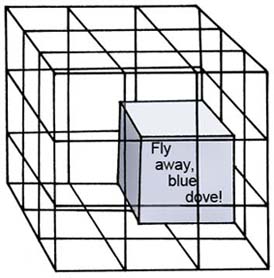

Rimma Gerlovina, Blue Dove, 1974.

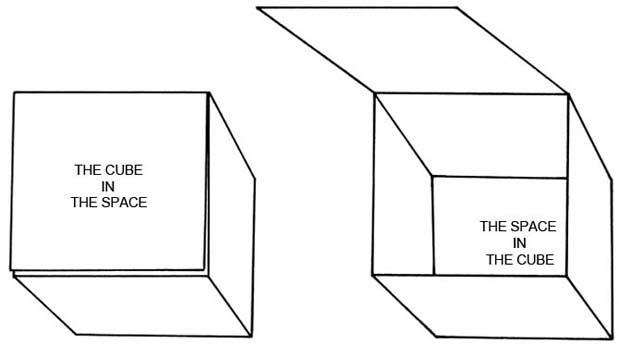

The idea of limitation, per se, is contained within the concepts of time and space, in which we are encapsulated. They represent this form of enclosure that might be identified as the very principle of life on Earth. What is it that is encapsulated here, the cube in the space or the space in the cube?

Rimma Gerlovina, The Cube in the Space, 2006.

The relationship of form to its spacing has its own trap; more than what quinto-sensory awareness is capable of grasping with ease. The cube is limited in space by its concrete shape; at the same time, space is also limited within this form, which turns into its cage. As soon as we reach for it, space eludes our grasp. When defined, the infinite becomes finite; it takes on form. Together with the form, the infinite obtains its limitation within it. But if we revert from the field of analytical geometry to the concept of the caged bird, that paradox will be even more paradoxical. If a cube is in space and space is also in a cube, does it mean that bird is in a cage and that a cage is also in a bird? That concept is on the verge of being bizarre, and yet, it does express the truth more fully. Thus, limitation is also limited by its expression; it includes its own illusion and indicates the relativity of these very bars behind which the bird finds itself free.

Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Bird © 1989, C-print.

Many ideas of our early work found their further expression in our performances, sculptures, and finally, in our conceptual photography. The image of Bird (1989), made fifteen years after the cube with a bird in a cage, clearly points to the same metaphor. Now instead of the text object, there is the subject that plays the main role. The focus shifted from the strictly mental concept of the cube-cage to the psychological means of its interpretation. Exhibiting thoughts and feelings, we made the face talk. There are certain moments in life that bring to mind a bird beating its wings against the bars of its cage. For the soul is traditionally associated with the bird, the material world is both a cage and a field of dance. That brings an additional sacral element into the interpretation of the cage, since the idea of trapping is inherent in the trajectory of the soul as it reaches materialization by the body itself, in which our souls are conditioned.

Rimma Gerlovina, Installation view of the cubes in Nächst St. Stephan Gallery, Vienna, Austria, 1979.

The idea associated with flying, or rather, levitation as opposed to gravitation was already implicit in the concept of the "floating" exposition of the cubes. In 1979 in the Nächst St.Stephan Gallery in Vienna, Austria, and later in America, the cubes were exhibited as hanging by strings from the ceiling, thereby visually organizing a sort of miniature galactic space. Wandering among these small "floating" bodies, spectators could manipulate every cube. Many years later, we came across a similar image in a passage of C.G.Jung: "it seemed to me as if behind the horizon of the cosmos a three-dimensional world had been artificially built up, in which each person sat by himself in a little box... and now it had come about that I – along with everyone else – would again be hung up in a box by a thread."2

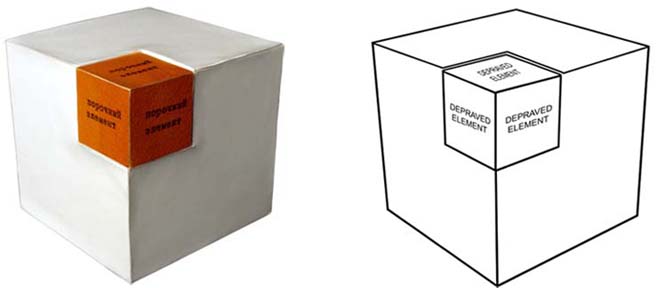

Rimma Gerlovina, Depraved

Element: With the removal of the small orange cube titled "The Depraved

Element," the perfect shape of the white cube, one of the five absolute

Platonic solids, is destroyed. 1974, cardboard, wood, paper, 3¼ x

3¼ x 3¼". |

.

The casuistic duality of nature can be illustrated by many means: the white cube with the orange Depraved Element (1974) is one of the samples. As a cube, it represents one of the five absolute Platonic solids. However, if one removes the small orange block symbolizing a depraved element, the perfect shape of that Platonic body is ruined. Every truth has a grain of mistake, and every mistake can have a grain of truth. When the ancient Chinese masters made their art objects, they used to add a tiny almost invisible dent. They thought that the nature of our earth does not tolerate perfection, and that if they themselves did not make slight damages to their work, nature would interfere in a much worse way. Dante echoes the same idea in his Paradiso:"But nature always gives it defectively, working like the artist who in the practice of his art has a hand that trembles." (Canto XIII) Does this mean that the world is governed by chance and error? It depends on the degree of one's openness towards the archetypal. The world is full; there are no empty niches; and a definite hierarchy governs the scope of ideas, beings, and things. And some of them can be quite depraved. One thing that is certain is that as soon the uncorrupted Platonic body loses the adverse depraved element, it will also lose its conceptual twist. If so, there is no drama in the plot anymore, and no one can "delight" in paradox.

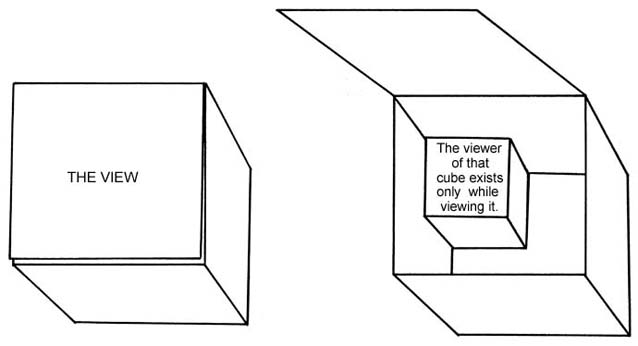

Rimma Gerlovina, The View, 2008.

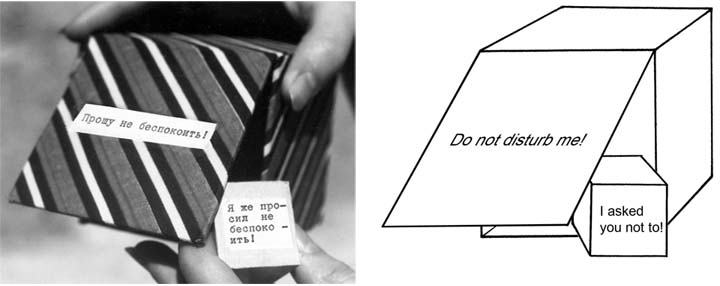

Rimma Gerlovina, Do Not Disturb Me! 1974, cardboard, wood, paper, fabric, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼".

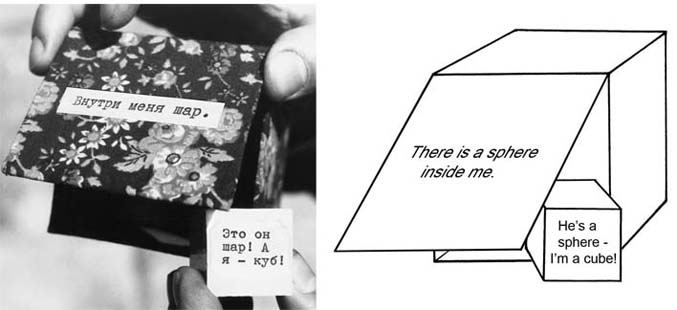

Rimma Gerlovina, A Sphere Inside Me, 1974, cardboard, wood, paper, fabric, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼".

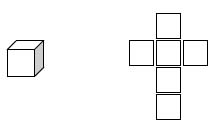

Many geometric figures allude to important symbols that are only partly decodable. Let us contemplate one of them. The cube can be presented in two forms: folded and unfolded. While in folded form, a three-dimensional body symbolizes matter and all that is earthly and bodily because it has stability and gravity. When it is unfolded into a two-dimensional cross, its stability and gravity are "crucified," to use a conceptual metaphor of one domain to reason about the other.

In many old doctrines with a legitimate perennial paradigm, the cube is associated with the human body that contains a divine spark, compressed within homo-cube. With its unfolding into a cross, that spark is set free. Some things that are physically effective are not physical at all. The same principle is reflected in the Kaaba, the Islamic house of worship in Mecca. Built in a form of a hexahedron, it can serve as a religious analog to the cube. In the Biblical version, each of the six sides of the unfolded cube represent one day of creation; and the last one (the seventh) which is not of that cube anymore, is its mystical crown. For this reason, many pilgrims have mapped out their lives on that unfolded cube, whose fundamental parameters are the same in different universal teachings.

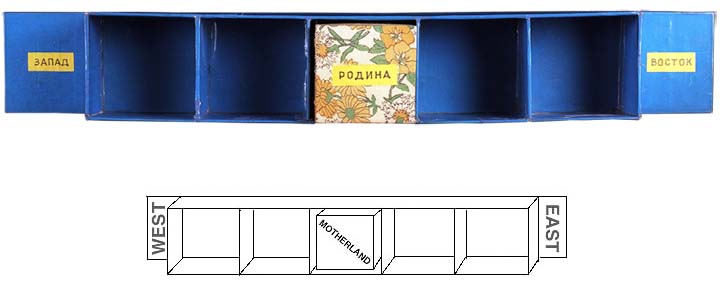

RimmaGerlovina, Motherland: the cube "Motherland" can be moved between the east

and the west. 1975, cardboard, paper, fabric, 21½ x 3¼ x

3¼". |

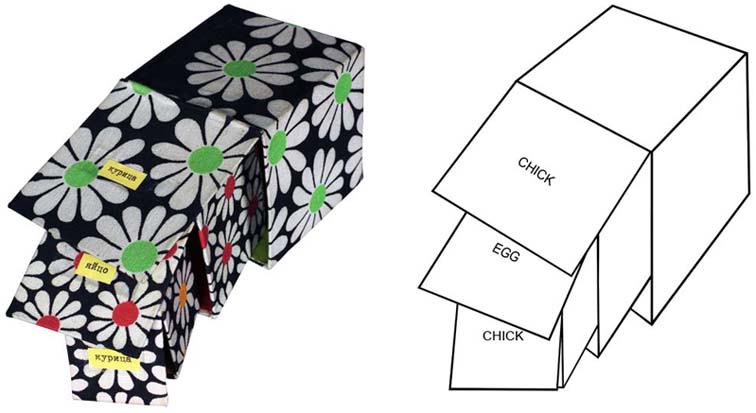

Rimma Gerlovina, Chic – Egg, 1974, cardboard, paper, fabric, 3¼ x 3¼ x 3¼".

--------------------

2/ C. G. Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections (New York: Vintage Books, 1973), p. 292.