< home < content next: Photo Concepts >

RIMMA GERLOVINA AND VALERIY GERLOVIN

TRESPASSING

(A SHORT OVERVIEW OF THE ARTWORK)

© 2010, Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin

PART 3: VALERIY GERLOVIN THE OBJECTS

From the beginning, Valeriy tried to trace the initial seed patterns out of which nature cast out her paragon of shapes. The abyss or division between divinity and humanity is filled with a variety of archetypes, which run the gamut from live beings to inanimate objects. His geometrical works, be they graphic series, oil paintings, or objects, appear like x-rays of the imagination, which reveal only typical content and skip the rest. Such are his early series of monoprints Road Signs (1973), featuring topographical landscapes, and Figures (1974), based on the matrix of an invented script. The process used to produce the latter series was rather unusual: Valeriy made the prints in colored carbon paper using a variety of techniques, including exerting heat and pressure, drawing, and punching holes.

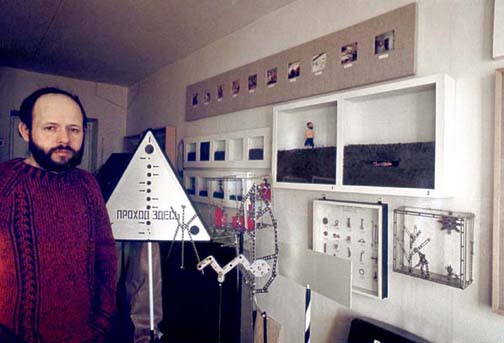

Valeriy Gerlovin with his works of 1974-77, Moscow, photo by Igor Makarevich. |

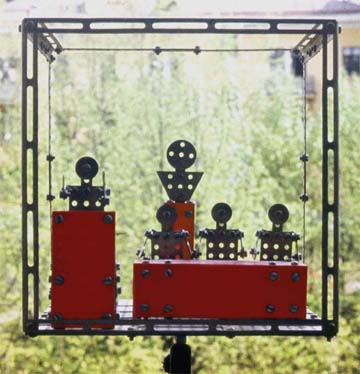

In 1974, he began to work with natural elements - metal, earth, and bread - in sculptural form. Using metal erector sets, he assembled different linear forms, objects, and three-dimensional scenes; some of them were mounted on metal stands, while others were displayed on the wall in glass cases in the manner of butterfly collections.

Valeriy Gerlovin, Metamorphosis of a Frog, from the series Objects from the Historical Museum, 1979, steel erector set, cardboard, paper, glass, 14½ x 20 x 1¾". |

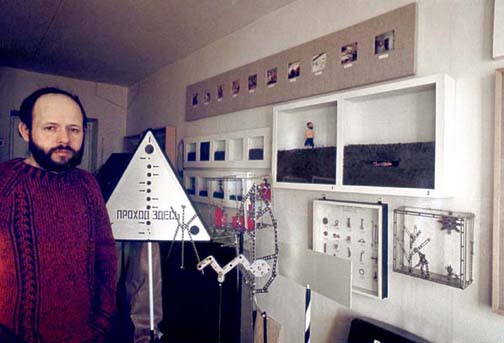

For example, in The Metamorphosis of the Frog three metal amphibians depict the sequence of the mutation from tadpole to fully-grown frog. Two tree branches, a real one and its stainless-steel replica, are displayed in correlation to each other in two windows in the herbarium titled Branch (1975).

Valeriy Gerlovin, Brunch, from the series Objects from the Historical Museum, 1975, tree brunch, metal, mazonite, glass, enamel, 10 x 17¾ x 1½". Private collection, New York. |

In Valeriy's series of metal objects, he found the seals and fragmentations that might be termed "the geometry of nature," the best theoretical model of which is described by the fractal relationship of everything to everything, wherein big and small repeat each other albeit on a different scale. Partitioned into the manageable pieces of the erector sets, Valeriy's sculptures carry the scale alongside the fragmentation. The bits and pieces of the erector sets can be assembled into one coherent whole; at the same time, their order contains a multiplicity of subordinated parts whose precision and structure exhibit a certain relationship to mathematical sets. Perhaps some parallelism in the artistic openness to the general outflow of world ideas can be in seen in the fact that Fractal Geometry dates to 1975 - the same year that the erector sets "flowed" from Valeriy. The laws underlying the regularities of nature can be shown not only by formulas but also by the intuitive artistic investigation that is similar to the impact of music, described by Leibniz as the pleasure the human soul experiences from counting without being aware that it is counting.

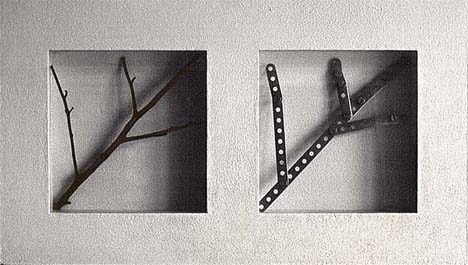

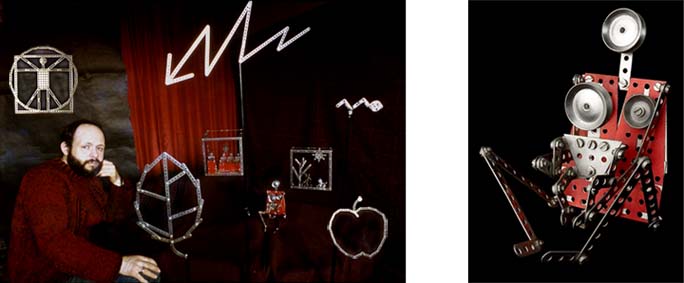

Valeriy Gerlovin with his sculptures from the erector set, Moscow. From left to right: Leonardo's Man, Leaf, Lightning, A Party Meeting, Madonna and Child, Garden, A Spermatozoon, Apple, 1974-76. (Right) Madonna and Child, 1976, steel erector set, plastic, 8¾ x 4¼ x 3½", 2 variants, one of which is in collection of The State Tretyakov Gallery. |

Art helps embody the modes of being in an abstract and removed manner. The distance may vary from macro to micro, as in Valeriy's sculptures Lightning and A Spermatozoon. In the latter, he makes a biological attempt to trace an invisible device of nature by assembling a male reproductive cell from an erector set. A bolt of lightning and a spermatozoon can be viewed in equal ratio to each other as objective and subjective forces symbolically showing the same penetrating, fiery power of nature, one demonstrated in the sky, the other in the human organism. Other emblematic geometric characteristics of the human body are captured in Leonardo's Man (picturing man within the circle and the square) and the sculpture Madonna and Child. The technical austerity of Valeriy's image of motherhood in its shorthand visual formula is repeated in many other works.

Valeriy Gerlovin, A Party Meating, 1975, erector set on the stand, steel, plastic, enamel, 10¼ x 10¼ x 8", stand 45" high. Collection of The Museum of the Berlin Wall, Berlin, Germany. |

In the erector-set mise-en-scène A Party Meeting, Valeriy geometrizes the sociological structure of the event depicted. Having graduated as a stage designer from the School-Studio of the Moscow Art Theater of Stanislavsky (MKhAT), he often applies his learned skill of making hyperrealistic scale models. Operating in abstractions but not burdened by them, he uses representative rather than actual historical precursors. Thus, in depicting the fundamental qualities of objects and ideas, Valeriy strips them of the affections of the senses, bringing them closer to the Kantian qualities of a thing-in-itself, in which the unique, imperishable matrixes multiplied by time and space become innumerable perishable objects. Highlighting only the essential ingredients as being necessary for the understanding of the whole, Valeriy tries to create forms that should rather be called meta-forms. The blueprints of ideas abide in our memory storage; therefore, their live representations can be easily recognized in art, especially in its conceptual branch.

Valeriy Gerlovin, Interring, performance in Izmailovsky Park, Moscow, April 26, 1976, clockwise: the artworks are exhibited, demounted, placed into the hole, and interred. Photo by Viktor Novatsky |

In 1976, Valeriy's erector-set sculptures played a fatal role in the performance Interring. The guiding star of this action was nature itself; if carried to the extreme one can revert to its central law, which dictates that nothing can be preserved here on earth ad eternum. Any culture, however rich, can be only a temporal pattern of life. Considering the fact that every order that follows a recurrent chaos only precedes another chaos, Valeriy played the sequence in four movements: the assembly and display of the works, and their subsequent disassembly and burial. Thus, his metal works that bear the seal of art and of nature were literally returned to their source, eventually becoming ore fossils. Preserving the general scenario of life that buries all that it produces, he rotated it on a much higher speed. Did he get a speeding ticket? Probably, yes. But he is not alone: the meticulous sand drawings made by the Buddhist monks in the open air were not intended for long lives, either.

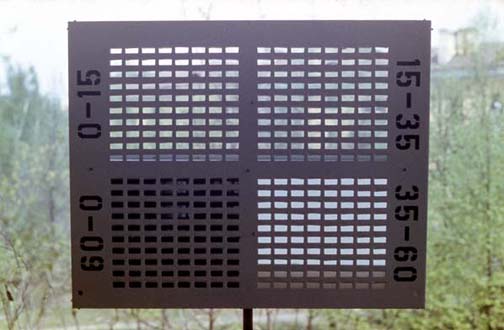

Valeriy Gerlovin, The Age Apparatus: In section 0-15 the window is empty, in 15-35 - glass, 35-60 - frosted glass, 60-0 - mirror, 1974, heavy metal, enamel, 20 x 25¼ x 8¼", stand 36" high. |

Valeriy also created a variety of metal objects out of various ready-made parts. One of them, The Age Apparatus (1975), depicts the process of the narrowing vision of the world in proportion to the aging process. The metal box with the front grid, through which one can see the interior, is divided into four sections. The first is for ages zero to fifteen; the window behind that grid is left opened. In the second, for ages fifteen to thirty-five, the window is glassed; in the next, for thirty-five to sixty, the glass is frosted; and in the last, for sixty to zero (i.e., until death), the looking glass occupies the entire field of vision. In a gradual descent through planes of increasing opacity, one is alerted to the merciless impulses of time and one's own instinctual habits, reflected in George Orwell's remark that at fifty everyone has the face he deserves. In the later years of our life, we are able to evaluate experiences more sensibly; at the same time, as our bodily vigor diminishes suppressed thoughts about permanency increase, trying to counterbalance the otherwise unpleasant process of aging. The Sages, who came to terms with the eternal at a later age, while seeing the whole world in the mirrors of their consciousness, were said to have undergone a natural process of revival. It is that kind of natural revival that goes against nature itself since the latter continues to keep us aging.

In the line of Valeriy's concepts based on three raw materials, metal, earth, and bread, One Square Meter of Earth (1975, 1 x 1 x 0.1 m) is the first and most virginal work of his land art series.

Valeriy Gerlovin, The view of the studio in Moscow, in front One Square Meter of Earth, 1975, soil, Plexiglas, 1 x 1 x 0.1 m or 39½ x 39½ x 4" (photo with the drawing.) |

The transparent plexiglass construction contains nothing but earth. The composition of that earth is as typical as it may be; in a way, it is a picture of itself. It includes all its organic and non-organic components, even peculiar patterns burrowed by earthworms, which make intricate pictures of their otherwise obscure lives. Such hyperrealism bordering on blunt abstraction unites the most direct with the most general. The land art series includes many objects filled with soil, such as the glass Globe and a variety of reliefs with glass windows.

Valeriy Gerlovin, Globe, 1975, soil, glass, plastic, metal, diam. 8¾" or 22.9 cm, stand 5" |

Valeriy Gerlovin, One Square Meter of Earth and The Globe at the exhibition "Moscow Conceptualism. The Beginning" at Arsenal Kremlin, Nizhny Novgorod, Russia, 2012. Curator Jury Albert. |

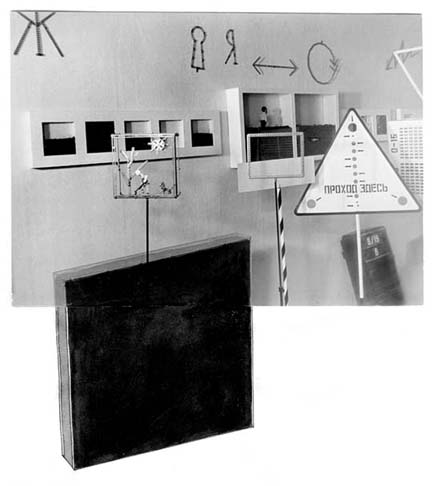

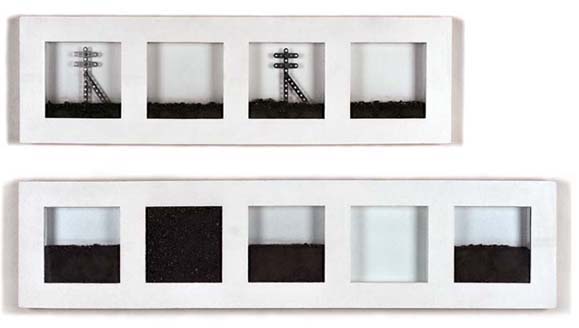

Out of the windows of the wall construction titled The View from the Train (1975) one can see a monotonous landscape made of earth, while in Oscillation (1975) the earth patterns trace the universe's complexity while revealing its underlying simplicity.

Valeriy Gerlovin, Train (top), soil, steel, masonite, glass, enamel, 10 x 33 ½ x 1 ½". Oscillation (below), 1975, soil, masonite, glass, enamel, 10 x 41¼ x 1½". |

Earth is equal to earth as it is depicted in the object Earth - Earth (1975), which suggests that philosophic matter, symbolized by earth, is self-equal. What exists alone exists. The matrix, in which our life is imbedded, is equally creative and destructive. It has self-fertilizing content, when nature under the sway of necessity is changing everything without changing its substance. In such context, matter (or earth as its symbol) might be abstracted even more as it is shown in the relief Emptiness - Earth (1975), in which its presence is equated to its absence.

Valeriy Gerlovin, Earth - Earth and Emptiness - Earth, 1975, soil, mazonite, glass, enamel, 10 x 25½ x 1½" |

Emptiness fills out the space with its geographical vacuum. As it said in Tao Te Ching: "Vessels are made of clay. Yet their usefulness depends on the empty space inside them." (1) From one point of view that visual formula hints on an illusory permanence in life, appearance versus reality, while from another, it pertains to the philosophic meaning of emptiness (as sunyata in Buddhism.) Emptiness in its fullness opens another dimension of reality that exists without existence, being something and nothing simultaneously. Back to back, reality and illusion compose that sunyata or cosmic emptiness. The white color is equally significant for that series: it is a color without coloring, which blending with the white walls seems to continue the saga of the vast impersonal. Emptiness is full of real sense; it works by its non-doing. For most people, the meaning of emptiness is inconceivable as opposed to the hectic fullness of life. Yet, it seems that genuine fullness cannot be full unless it include emptiness as well.

Valeriy Gerlovin, Life of a Man in Two Parts, 1975, from the series Objects from the Historical Museum, masonite, glass, soil, toy mannequins, enamel, 18 x 34¾ x 4¼". |

Earth is our inhabitance; it is the substance of our planet, our source of nourishment, and our confinement, as shown in Valeriy's burial-like work with two toy mannequins, Life of a Man in Two Parts. With striking bareness this object deals with the problem of "to be" and "not to be." Everyone born is bound to die. And our living planet is in fact a massive burial site. The ancient Chinese sources inform us that the compulsory rest in the terrestrial realm is necessary for the "return of vitality through the heavenly aspect... because the extinction of yesterday is necessary for the preparation for tomorrow. After all, we do not only live in one time, but we live, as it were, in an onion of different time shells." (2) In such a short article, it is better to condense the discussion of death and earthly dust into a couple of simple thoughts: death is a regression into hiddenness, dust is also a cosmic material, and cosmos in Greek means "order."

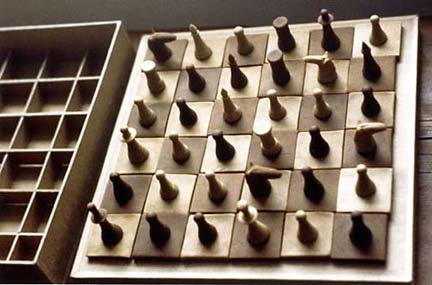

Using another natural material, Valeriy sculpted from bread as if it were clay. That pseudo earthenware art was prompted by his natural tendency from childhood to roll little pieces of bread into different forms, as in A Chess Game, made out of white bread and pumpernickel.

Valeriy Gerlovin, A Chess Game, 1980, bread, cardboard, 12½ x 12½ x 3¼". Jean Brown Collection of Dada, Surrealism, and Fluxus, The Getty Museum, CA. |

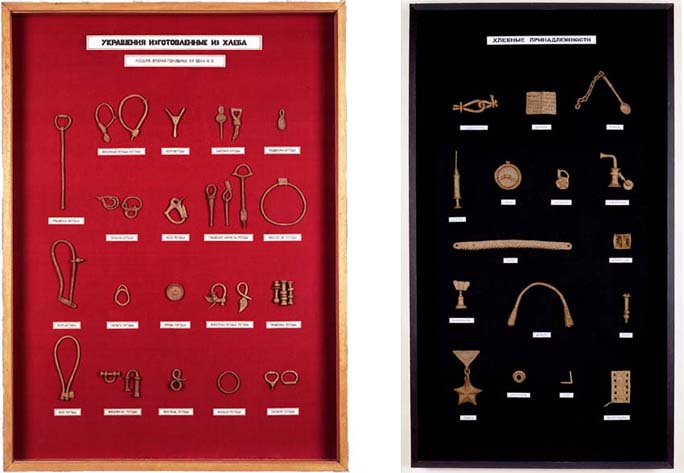

He displayed his little bread objects in glass cases of different types: Collection of the Non-Smoker (1976), Russian Jewelry of the 20th Century (1976), and The Bread Tree series (1976-81), the last featuring a variety of Bread Insects.

Valeriy Gerlovin, (left) Jewelry from Bread. Russia, second part of XX cen. A.D., 1976, bread, wood, fabric, paper, ink, plexiglas, 33 x 24 x 3½". Collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art Art4RU, Moscow, Russia. (Right) Bread Utilities,1979-81, bread, wood, fabric, plexiglas, paper, ink, 37¼ x 21 x 2". |

In parallel with his manually-produced pieces, Valeriy exercised his linguistic facilities in a bizarre form - in the manner of pronouncements on a range of issues, domestic, social, and philosophical. All his tongue-in-cheek Pronouncements were accompanied by drawings and addressed to his spouse, nicknamed "Bura-Le," who was in charge of all external duties in the world (including arranging celestial processions), corresponding to the interplay of male and female forces (much like purusha and prakriti in the Vedic tradition).

In New York in the early eighties, our Manhattan loft-garage on Spring Street was crowded with new conceptual works. They obtained a different face but retained the same message, albeit modified under the new conditioning. It seems to us that we moved from the early "Greek" sensibility characteristic of our Moscow period to the "Roman" monumentality of forms typical of our time in New York. If Rimma's cubes grew into full-size statues of cubical men, Valeriy's works were blown-up into the fragmentations of faces and heads with bulging mosaic eyes made from paint syringes. In 1982 he began his Ancient New York Mosaics Series.

Valeriy Gerlovin, view of the artist's loft, New York, 1983. Ancient New York Mosaics Series, from left to right: Profile, 1983, The Dog, 1982, The Shadow, 1983, each 96 x 48 x 5"; Soldier, 1982, each part 96 x 24 x 5"; The Third Man, 1982, 44 x 28 x 3½"; The Dove, 1983, 14 x 15 x 5", canvas on homosote, syringes, oil, acrylic. |

![]()

Valeriy Gerlovin, Large Icon and In the Beret, 1984, from Ancient New York Mosaics Series, canvas on curved homasote, syringes, acrylic, 72 x 29½ x 10" and 48 x 27½ x 9". |

During this period, Valeriy began to paint faces and long figures on large, upside-down wooden staircases. Each inverted step housed a fragment of the painting, and the sum total of these segments unfolded into one complete artwork.

Valeriy Gerlovin, Staircase Crowd, 1986, and Staircase Man, 1985, wood, acrylic, 120 x 30 x 9" and 125 x 21 x 9". Installation view of the joint retrospective exhibition An Organic Union (Fine Arts Museum of Long Island, Hempstead, N Y, 1991.) |

Soon, the heads from the paintings and sculptures received monumental treatment in murals made right on the walls of galleries. Valeriy's most interesting mural was done in less than a week's time in 1984 in the enormous space of the Mattress Factory Art Museum, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. While he was making the frescoes, Rimma shot a video that showed the whole process of creation in a rather parabolic way.

Valeriy Gerlovin, murals Ancient New York Mosaics, joint installation at the Mattress Factory Art Museum, Pittsburgh, PA, 1984 (From left to right) two Large Heads, approx. 144 x 195", Male Staircase (with the figure) 145 x 36 x 12"; Video Head with the video monitors in its eyes, 87 x 156". (Link to the museum website) |

Half buried in the floor, the mural heads looked like the anonymous spirits of some excavated ancient temple. We felt as if we were trespassing into something from illo tempore that we recreated and ritualized by our own hands. The video monitors were installed in the eyes of one of these guardians, adding a modern dynamic to our baldheaded installation, which looked like an intentional step into the ground where the humans and gods of the past were preserved in awesome majesty. The reflections on the shiny floor increased the sense of an abyss, while the low rhythmic sounds of the video (Ancient New York Mosaics, 1984, with music by Charles Morrow and Glen Velez) resonated in the vacuum-like space like a shamanic chant. We later made one more video, about our friend Jean Brown, the collector of Dada, Surrealism, and Fluxus. The video focused on her "artless art" and her disarming power of kindness (Not Jean Brown, 1987, edited by Mark Bloch, with soundtrack by John Cage).

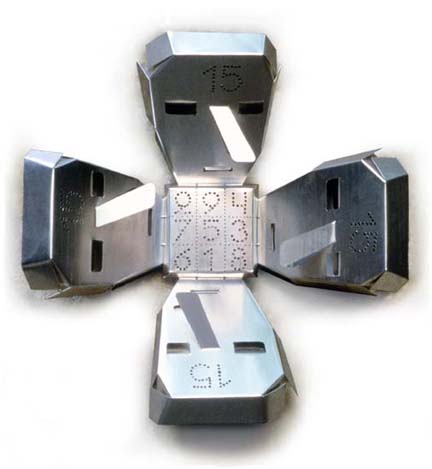

In 1985, Valeriy developed what is probably his most important series of metal reliefs, featuring cut-out heads and punched-out numbers. Dealing with different numerological symbols, many of these reliefs are made out of large sheets of aluminum, which are folded like origami. This method emphasizes the oneness of the matrix of creation and the unity that underlies the multiplicity of reality. Different numbers punched on these sticking-out heads reflect the ancient tradition of putting the seal of the lamb and the number of the beast on the forehead.

Valeriy Gerlovin, Homage to Pythagoras (Pythagorean magic square) 1987, 48 x 48 x 7", aluminum. |

His seemingly mechanical metropolis of human sameness usually presents numerical arrangements of magic square or the Pythagorean tetractys. They puzzle with its marvelous arrangements of numbers that stand to each other in a perfect harmony embedded in the concept of mathematical beauty.

Valeriy Gerlovin, Tetraktyes, 1987, aluminum, 45 x 46 x 6". |

The metal relief with the tetractys shows the paradigm of creation from one to ten, in which ten is a turning point of all counting, returning to the completeness and unity of one but on a higher octave. Postulating the reconciliation of the notions of unity and diversity, Valeriy at the same time stresses the need to recover identity out of the sameness inherent in life. In a manner typical of the conceptual vocabulary with its embrace of the absurd, he cut out and folded a seated figure of a chairman who is a kind of centaur (but in this case half man, half chair) with a protruding sexual symbol.

Valeriy Gerlovin, Chairman, 1987, aluminum, 38½ x 22 x 23". |

His series of magic squares reflects the Pythagorean concept of the physical universe as an immense magic-square arrangement of innumerable contrasting forces. In the simple magic square of order three, any three numbers in a row (horizontal, vertical, or diagonal) add up to fifteen. The number five, located at the crossroads of all other numbers, functions as a five-pointed star that traditionally symbolizes not only man, but a quintessential state as well. With this, Valeriy's magic squares touch on the same issues that lay behind Rimma's cubitis magikia, or "magic" cubology.

Valeriy Gerlovin, Magic Square (Chinese), 1986, 39 x 39 x 12", aluminum. |

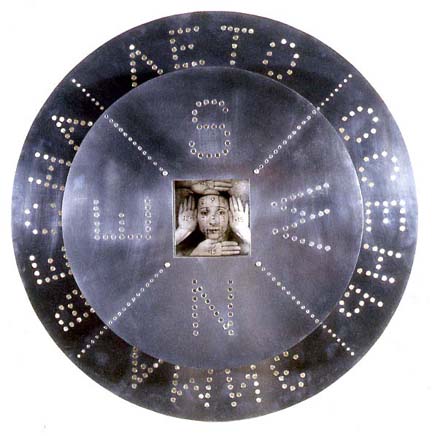

After several sculptures that incorporate the Chinese Lo Shu Magic Square, which works as a numerological mandala, Valeriy turned to the mandala itself, in which the earth is depicted as a formative square, as opposed to the circle of heaven.

Valeriy Gerlovin, Round Magic Square, 1987, 24" in diameter, 3½" deep, aluminum, b/w photo. |

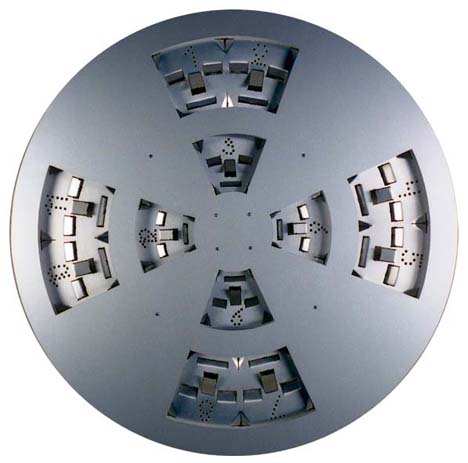

The move from the square forms to the circles was natural and timely for both of us. His new series of metal circles was connected to the idea of circular time, the compass, and calendar, showing the uniting notion of coiling time that is radiating around a single measureless point. These works inspire thoughts on the concept of time in an artistic manner. It is generally believed that time passes - maybe it stays where it is, while we pass around and around... Waiting for no man, time does not permit stopping or rewinding for a single moment.

Valeriy Gerlovin, Aztec Calendar, 1988, 33½" in diameter, 3" deep, aluminum. |

Toward the middle of the eighties, the nucleus of our art creation in three-dimensional objects was formed, and therefore ready for revision, expansion, and rejuvenation. The metaphorical realm of photography, the colorful mirage of "photomorgana," emerged from the seeds of our early performances, conceptual objects, and visual poetry.

Rimma Gerlovin and Valeriy Gerlovin, installation view of the joint retrospective exhibition An Organic Union at Fine Arts Museum of Long Island, Hempstead, NY, 1991. (Left) metal sculptures by Valeriy Gerlovin, (right) joint work Photoglyps. |

-----------------------

1 Tao Te Ching, translated by Mikhail Nikolenko, edited by Vladimir Antonov, (CreateSpace, 2001), ch.11. 2 Richard Wilhelm, Lectures on the I Ching, (Princeton University, 1979), pp. 22, 160.

|

LINKS:

< home < content next: Photo Concepts >