Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin

pHOTORELIEFS

© 2010, Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin

part 2: FLAT SOLIDS

The beginning of our latest series Photoreliefs can be traced to the

nineties. This series unites photography with metal reliefs. Valeriy’s metal

sculptures entered our photographic oeuvre in a distinctive, integral manner

when we began extending its form and meaning to the three-dimensional world of

objects. The earliest examples of that shift are the cluster installations with

kaleidoscopic effects and the structural compositions like IOU (1989, see Photoglyphs,

part 3) and Pi (1991).

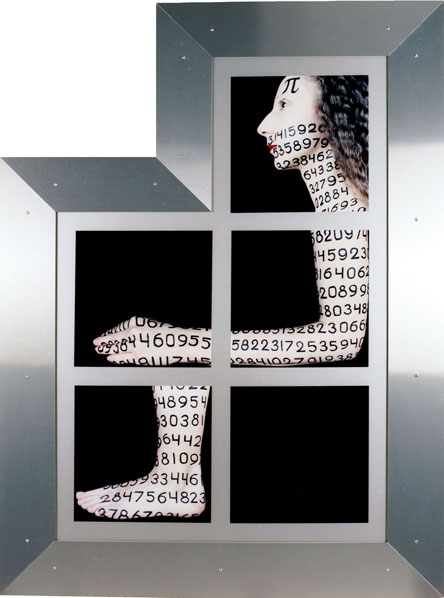

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Pi © 1991/2007, C-prints in aluminum construction, 48 x 36" |

Suffice it to

say that we had a rooted interest not only towards words and their engaging

“in-word-ness” but also towards Pythagorean number symbolism. Valeriy used the

language of numbers as a tissue for his concepts that he literally engraved on

his metal reliefs. Naturally, some of them found their way in our photography,

as, for example, irrational mathematical constant Pi in the architectonic photocomposition under the same title. Pi is labeled as a transcendental number;

it can be carried out to an infinite number of decimal places without ever

arriving at a solution (its first 16 millions of digits have passed all the

tests of randomness used on them so far). According to the old recipe, the

proof of the Pi is in the eating.

Therefore, the supposed solution known as “squaring the circle” was one of the

most famous problems of antiquity (Pi

is the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter). Yet, this number is above relation;

it is a constant because it holds for all circles, symbolizing a universal

synthesizing power.

| Page from To Infinity and Beyond, Special Exhibition Resource Guide for Teachers, The Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntington NY, 2008 |

As it is

known, the infinite is not exhausted by the infinite manifestation, as the Sun

is not exhausted with its scattering raying. To further continue the celestial

analogy, the universe also can be viewed as a plasma

of endlessly recurring decimals. Naturally, that “plasma” has its reflection in

the human organism in a microcosmic sense. In that view, inscribing Pi on the human skin seems to extend its

transfinite message from strictly abstract to artistic parameters. The static

and “archeological” composition of that photograph has some similarity with the

Ancient Egyptian block statues. We “flattened” the block and visually reduced

the number of the body limbs, giving them an ephemeral look

of limbs with no body, and inscribed on them that infinite number.

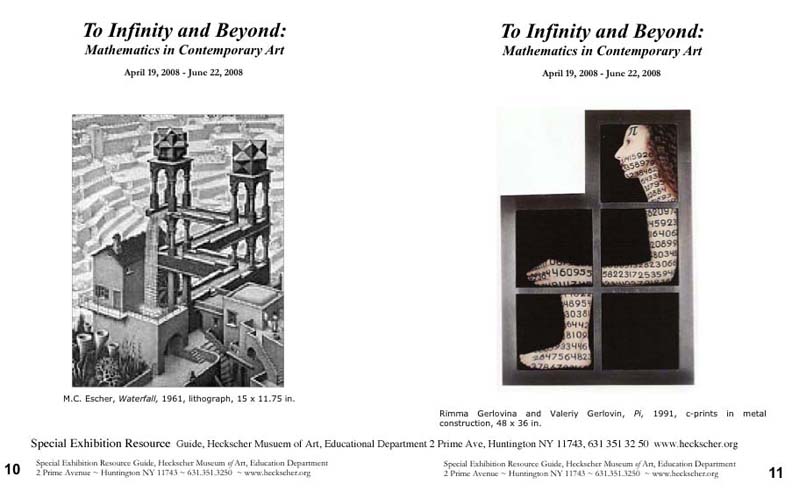

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Double © 1996, C-prints in metal construction |

The three-stage artistic process

– idea, creation, result – reflects the three interlaced layers of

existence – intellectual, sensible, and physical – each of which

corresponds to a particular level of consciousness. That tripartite process was

replicated in the series of Photoreliefs:

first, the ideas were born and processed into the photo concepts, which, in

turn, “solidified” into sculptural objects. Thus, the inner world received its

projection into the outer world, so they were bridged through conceptual,

aesthetic, and “hands-on” methods.

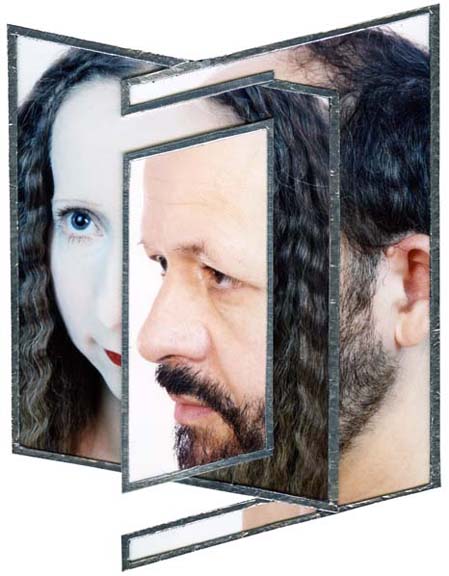

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Cameraman © 2008, C-prints in metal construction |

As in the other cycles, Photoreliefs includes several

sub-series, such as Flat Solids, Unfolded Reliefs, Circles, Cutouts, and Superstrings.

While endowing the images with volume and depth, we also sought to adhere to

the rules of photography. The sequence of Flat

Solids is based on optical illusion. Although at first glance the works

look like three-dimensional bodies, they belong to the same “flatland” of

photography: their metal geometrical constructions are actually two-dimensional.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, H2O © 1990/94, C-prints in stainless steel construction, 48 x 48” |

In the composition

H2O, featuring

pseudo-water in a pseudo-cube, the whirlpool of the “great deep” is created out

of hair, “incubated” in a similarly flat solid. The waterfall of hair increases

the illusion of the flat composition that appears as a cube. Here we tried to

unite a fluid indefinite form with the precise geometrical formation. The

visual images can give us a clue to the abstract thinking and subsequent analogies.

In that architectonic arrangement of “liquid," the perturbation of water seems

to redirect the whole system, which is only skin deep chaotic. Beneath it,

there is an intricate structure of regular periodic motion; in other words, the

universal matrix of the “great deep” in its receiving and creative state. Water

that always follows the path of least resistance is depicted live, staying in

perpetual circulation. Marked with the chemical seal of H2O, the alchemical

aqua permanens (enduring water) turns

the wheel of the moon calendar.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Möbius Strip © 1993, C-prints in metal construction |

Rotating with

tension and release, the enduring supply of aqua

vitae maintains the existence and preserves the ashes of dust from the

final diffusion. Following its Möbius Strip, it always returns to its

starting point having traversed every part of the strip without ever crossing

an edge.

Every living

creature plunging into a liquid phase of its formation passes through pre-birth

darkness and its chaos. Deepened into the baptistery of its mighty energy, not

only one stays alive but also is invigorated by turbulent waters of one’s own

“aquarium.”

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Waterfall © 1993, C-prints in metal construction |

The waterfall consists of drops that fall and disappear being renewed over

and over again. Such is life – the formation of an uninterrupted new

beginning of an uninterrupted inevitable end. In that context, the notions of “beginning”

and “end” are just a conceptualization. The cascades of waterfall show the

succession of moments that are passing by and immediately reconstruct

themselves, waving the metaphorical ripples of waters. On a psychological

level, people are involved in the perpetual process of sinking and emerging,

entering and leaving, and not without similarity to the waterfall. It seems

that each individual is preserved like a single drop of water; each helps to

swell the ocean.

Waterfall is one more visual metaphor for the structural chaos

of the irrepressible stream of life and the arrangement of that stuff which

likes to be uncontrollable. It often happens that symbols attract the things

that they symbolize, and vice versa; things evoke

their symbols. We seemed to experience it while visiting Niagara Falls not long

before we made this work. The shaky law of coincidences helped us to look more

precisely at the meaning of this “watery” subject and inspired us to put

another individual drop in its deep waters.

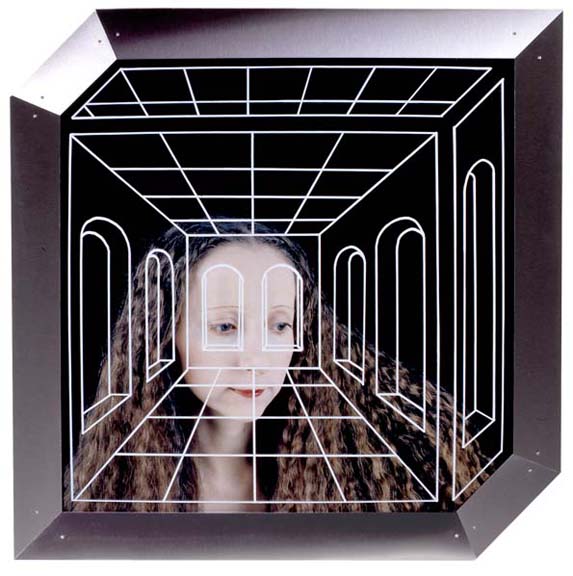

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Perspective © 1992, C-print in stainless steel construction, 48 x 48” |

In Perspective, the architectural perspective drawing creates an

illusion of three-dimensionality. The face was photographed through the

Plexiglas with the drawing of the Quattrocento-like panorama, in which the

proportions between the real and the imagined, the face and the architectural

structure, became adjusted. Here, the impersonal was configured through the

personal and vice versa, creating something of an artistic convergence between

a man and his temple. As all old temples were conceived according to the canon

of the scale of man himself, our Perspective

followed the same rule. As always, man is the measure of all things in both his

own life and his environment, no matter what he preaches.

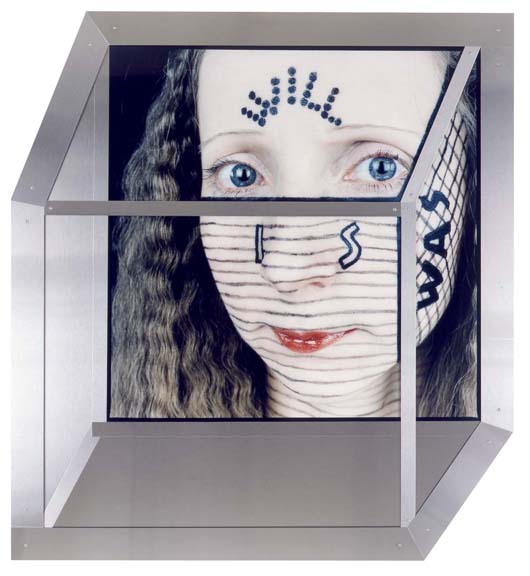

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Was–Is–Will © 1992, C-print in stainless steel construction, 48 x 44” |

Like Friar Bacon's brazen head, I've spoken,

"Time is," "Time was," "Time's past."

Lord

Byron, Don Juan, i. 217

The

concept of time goes through all of our art in the manner of Ouroboros, the

tail-devouring snake, assuming different forms and substances: linear, spiral,

liquid, sandy, cubic, and, of course, anthropomorphic. The eternal relates to

the temporal physical life as time relates to a clock face – whether it

exists or not, it makes no difference for time. It reels itself off through

eternity. The direct grasp of eternal ideas is impossible when one is locked

within the laws of man’s normal space-time-continuum. For that reason, the

creative arts help us to fill this gap with imagination capable for time

traveling between the worlds (and the words.) More precisely, the Flat Solid

composition Was–Is–Will

depicts the cube “locked” within the space-time-continuum. That might be expressed in a variety of ways: verbally, visually, mathematically, or blended together in one unit.

√I = was I = am I2 = will

What is the

square root of “I” or the self? Perhaps, it belongs to the past. At the present

time, “I am that I am,” to borrow the biblical pronouncement in a humble way.

And what about the future? One raised to the second power? Will he or she be squared?

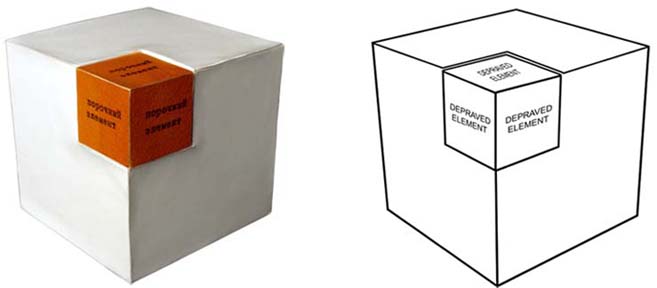

| Rimma Gerlovina,Depraved Element © 1974, cardboard, wood, paper, 3 ¼ x 3 ¼ x 3 ¼ |

With the removal of the small

orange cube titled “Depraved Element,” the perfect shape of the white cube, one

of the five absolute Platonic solids, is destroyed. Or if

Many

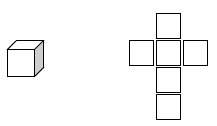

geometric figures allude to important symbols that are only partly decodable.

Let us contemplate one of them. The cube can be presented in two forms: folded

and unfolded. While in folded form, a three-dimensional body symbolizes matter

and all that is earthly and bodily because it has stability and gravity. When it is unfolded into a

two-dimensional cross, its stability and gravity are “crucified,” to use a

conceptual metaphor of one domain to reason about the other.

In many old doctrines with a legitimate perennial

paradigm, the cube is associated with the human body that contains a divine

spark, compressed within homo-cube. With its unfolding into a cross, that spark

is set free. Some things that are physically effective are not physical at all.

The same principle is reflected in the Kaaba, the Islamic

house of worship in Mecca. Built in a form of a hexahedron, it can serve as a

religious analog to the cube. In the Biblical version, each of the six sides of

the unfolded cube represent one day of creation; and the last one (the seventh)

which is not of that cube anymore, is its mystical crown. For this reason, many

pilgrims have mapped out their lives on that unfolded cube, whose fundamental

parameters are the same in different universal teachings.

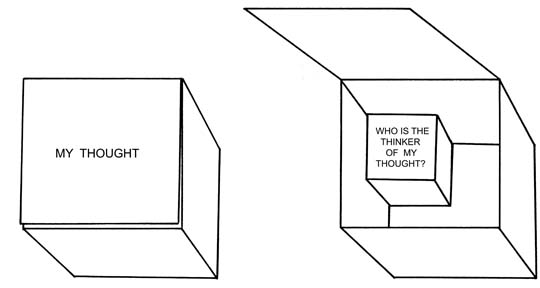

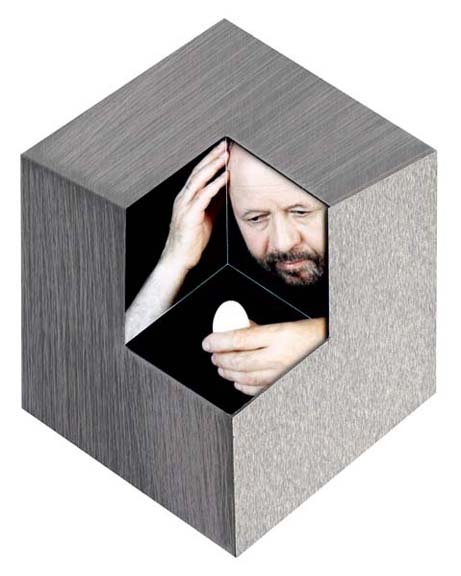

Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Cube Insider © 2008, C-print in metal construction |

The metaphoric impact of these homo-cubes does not

inhibit a possibility of their polyvalent interpretation. Neither the brain is

the mind, nor the mind is the consciousness – but together, they

represent a crossword for their carrier. However, through the thinking process

and its “vibraining,” one comes closer to the physical expression of the

consciousness. Perhaps the Buddhist koan about two disputing chelae can illuminate

that idea from a different perspective. One of them says: “The weathercock is

moving;” the other opposes: “No, the wind is moving;” while upon hearing this,

their teacher concludes: ”Your minds are moving.”

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Mind-Wind © 1992, C-prints in aluminum construction with pencil drawing, 72 x 46” |

Our photographic twin-like composition Mind-Wind depicts the similar idea:

“mind” is written on one forehead, while on the other, it turns into “wind.”

Both photographs are printed from the same negative, but the second one is

flipped over. With what are we dealing here: “windless mind,” or “mindless

wind’? This is one more conundrum to contemplate.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, The Watching Eye © 1992, C-prints, reproduction in The New York Times Magazine, 9. 19. 1999 |

The Watching

Eye is also a Flat Solid

composition; it reflects both Russia’s religious

heritage and its social calamities. In

1999, exactly the day we landed in America 19 years ago, we received a proposal

from The New York Times Magazine to create

an image capturing Russian cultural and historical traditions for the Millennium Issue – a vision of the

past through time, reflected through the

creative imagination of different artists. Based on our comment, the title of

the editorial article has a political grasp – Big Brother’s Eye, Mother Russia’s Tears. The Soviet State gradually

intruded into the consciousness of the common man, who himself had become his

own watching eye in communist Russia. Resting on its temporary laurels, Soviet

socialism had developed into two simultaneously opposite directions: one towards

emancipation and the other towards the infringement of human rights. As Dostoyevsky predicted, “the most horrid crimes against freedom”

are committed “for the sake” of freedom. While true, there are more

comments on that thread.

In some

distant way, our work is a conceptual rendition of Andrei Rublev’s The Holy Trinity, the icon that was

counted among the most perfect and precious in Russia. This is not a place to

discuss the idea of the Trinity; it seems impossible to solve it, as it is

impossible to find the finite digit in the decimal expression of one third. Relation

of Unity and Trinity is endless:

1/3 = 0,3333333333333333…

On the “canvas” of the face, two figures are depicted as if they are

running down teas, while the third witness is just a watching eye. In Mother

Russia, it was always the face of the Motherland (in contrast to German Vaterland). Since each nationality has

its own picture of the feminine aspect, the Russian Madonna had distinctly

different psychological garments. According to Philokalia her “holiness and purity of soul is received through

fear of God.”1 Here we see an obvious stress on penances, hardships

of life, and the necessity of endurance, which is typical of Russian

iconography. It seems that the Russian character is made of a queer mixture of strength

and weakness, perseverance and vulnerability. Red-blooded fervor is often

afflicted with inertia. Something in this national soul is very delicate and psychic,

though not very healthy. Its intellectual passion is equal to the passionate

intellect; historically its great moral resistance has been imbued with the preaching

of suffering and hope for spiritual support.

In terms of the politics at the end of the millennium, the brutal

communist State has ground itself into dust, but that is a subject matter for

sociology and politics of which one can talk continually in a sinister way. To

get out of the domineering power of group thinking and the closed curve of the socium that holds many artists meddling

in hot social issues, one needs to acquire a more radical understanding than

the harsh criticism of society, which is, in fact, its immanent part. Let’s

make a generalization at that point. On a higher level, people are divided not

by nationality, but by consciousness. Only those who can be characterized by a

less developed consciousness are divided by nationalities, not being capable of

transgressing its boundary. Wise men geographically poles apart and sages of

different faiths immediately understand each other.

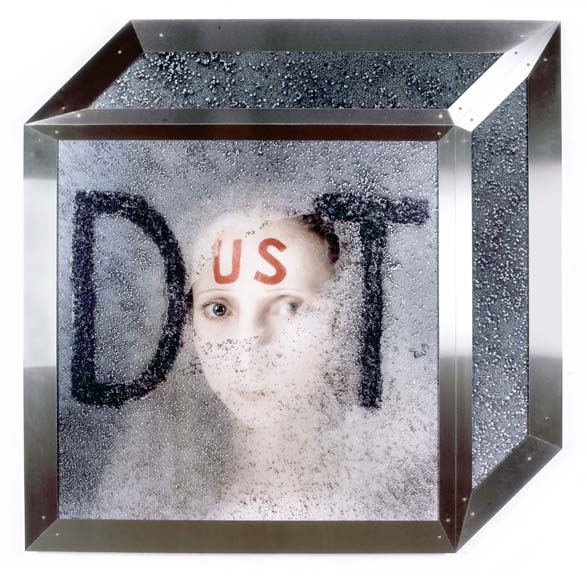

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Dust © 1990-91, C-prints in metal construction, 48 x 48" |

In the fictitious cube Dust, “us” is written in red letters on

the forehead, acting as a catalyst on that “polymerous” concept of death. The

dust per se is a symbol of our mortal

atmosphere, and the prophecy on that account in Genesis 2:7 is not very

promising. Yet, however grave the appearance of impartiality worn by the

eternal, it seems to “meet its end” in human consciousness. Since between birth

and death there is life, it is reasonable to expect that between death and birth

there is also life, but in a state of immersion, say, in such dust that our own

faces are hidden from us. The vitality of life, with its continuous flux of

expansion and compression of energy, cannot be simply left behind unless

metamorphosed into another form, even one completely undetectable. Dust’s context increases the illusion of

volume, bringing it into the square package of diffused particles, a

theoretically suspicious combination of shape and shapelessness. Therefore, at

this point it is better to condense the discussion of death and earthly dust

into a couple of simple thoughts: death is a regression into hiddenness, dust

is a cosmic material, and cosmos in Greek means “order.”

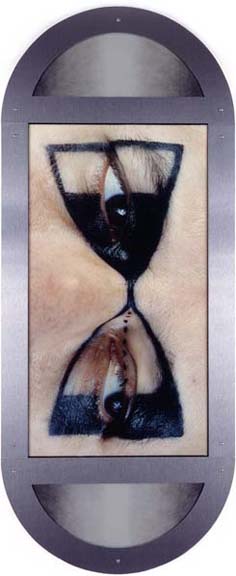

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Hourglass © 1989, C-print in metal construction, 43½ x 17¾" |

Watching a

flow between the bulbs of a sandglass, one can perceive intuitively how the

pivotal “now” operates between “before” and “after,” between our desires for

the future and our memories of the past. That is a zero point through which the

plus and the minus are processed. All happens as a single act. Even if it were

so, this single act is put on a loop, kind of a revolving hourglass. In a

horizontal position, the very shape of that device outlines the sign of

infinity. Time flows through our “eyeglasses” always too

![]()

Following the above-mentioned

precepts, we wrote a polylogue about death, while developing it upon the speculative background that has provoked the

intensive thinking of many minds.

UNLI’MITED

(A play for polyphonic voices for dramatic personae; no limit to their

numbers.)

Hamlet. (Moody) To be or not to be: that is the question.

Whitman. (Confidently)

Has anyone supposed it lucky to be born? I hasten to inform him or her,

it is just as lucky to die and I know it.

Socrates. (Aside) The business of a philosopher is a continuous

exercise in dying.

Eckhart. I was born to and for eternity and because of my

eternal birth, I shall never die.

Blake. (Pressing) I cannot think of death as more than the

going out of one room into another.

A voice from Amphitheater. (Mocking) A mosquito that dies daily is going

through the spinning door between these rooms incessantly, is it not?”

Mosquito. (Full of vital fluids) Bloody fools! I am what I

am!

St. Paul. (In a conciliatory way) I die daily.

Kierkegaard. (Sick unto death) For when I am dead, I am immortal.

Sri Aurobindo. (Thoughtfully) When I live or die, I am always.

Heidegger. (Clutching his garters with self-confidence) Why is

being altogether being and not nothing?

The Buddha. (Refuses to speak on the ground that affirmation or

negation equally raises misunderstanding.)

(The voices continue to grow and multiply interfering

with each other. Abrupt sentences in different languages are heard from the distance)

…raison d'źtre…

Who will deliver me from the body of this death?…

Mors certa, hora incerta…

Does not an infant die to become a child?…

E=mc2 …

La vita es sueĖo…

Death is merely a translation back to the soul’s

element…

Ding an Sich…

отдать

концы в

бесконечность…

memento…

more…

No end

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin,Void © 1989/94, C-print in stainless steel

con-struction, aluminum, pencil drawing, 48 x 41 ¾”

|

In the flat solid Void, the “voidness” of that very word

seems to fill all of its psychological space. Does non-existence exist? The

emptiness holds the maximum potential in its vacuum. It is a zero-point field

that contains the least irremovable energy. Perhaps, the concept of the

Buddhist sunyata presupposes the same emptiness in its potential wholeness. To

put it another way, exhausting all views, sunyata is not itself another view.

Emptiness and its mathematical expression, zero, might be observed in a variety

of ways, even via its antithesis, abiding by the proposition of the meeting of

extremes. For example, zero, which in our works often assumes the form of an

egg, conveys its potential in an organic way.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Egg © 1992/94, C-print in aluminum construction with pencil drawing, 42 x 32” |

The flat half-spheroid Egg contains a nest of hair within the

egg as the potential for yet another egg and so forth ad infinitum. The metal relief’s illusion of volume was achieved by

its cut-out form, along with subtle cross-hatching in pencil. The embryo develops within the egg when the reproductive

cell is fertilized. The egg seems to be a chicken's way of making another

chicken. It's different with people, some of them are able getting real eggs

from illusory chickens. Analytically, the egg is an organic (or creative) end

that hatches its own beginning.

Following the same rules in

the development of the series Photoreliefs, we can move from Flat Solids to the next Unfolding

Series that continues 3D illusion giving rise to a corresponding

deceptive “algebra” of the imagination.