Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin

pHOTORELIEFS

© 2010, Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin

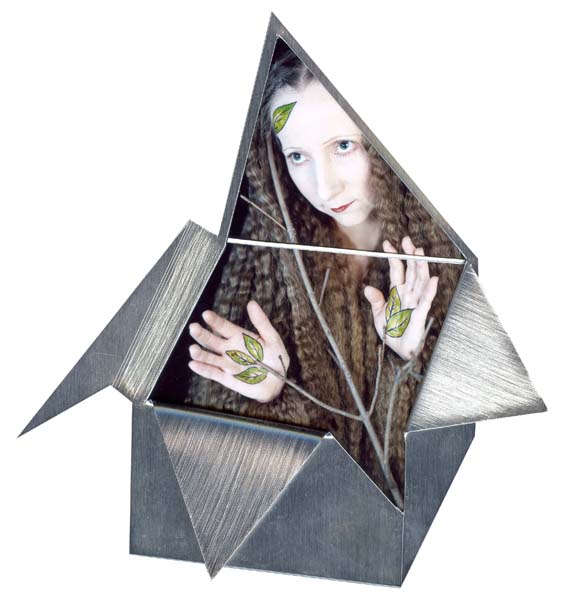

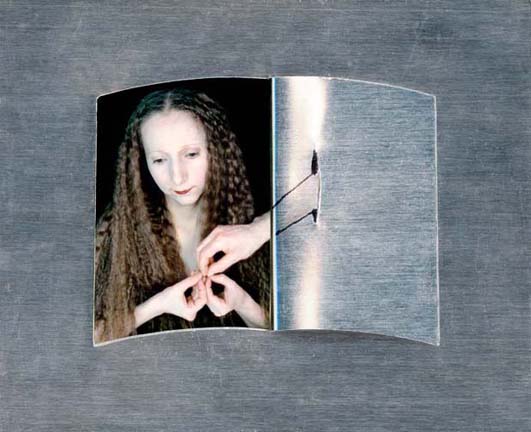

part 2: UNFOLDING SERIES

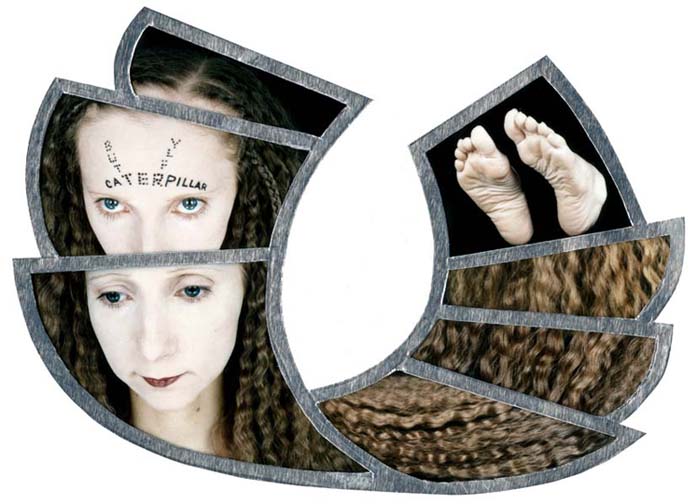

The main feature of the Unfolding Series is that all of its reliefs indeed seem to spread out from a folded state, depicting a process in which something passes by degrees to a different perhaps more advanced or mature stage. Some of them are produced in a manner akin to that of origami. The photographs of various parts of the human figure are inserted into flat metal compositions, creating the illusion of bending, sitting, spiraling, jumping, or gradually unfolding into something “other,” just as a caterpillar unfolds into a butterfly.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Caterpillar – Butterfly © 1993, C-prints in metal construction |

The individuality is born on the basis of a dissolving personality of so-called natural man. To recall the burial of a silkworm in its cocoon, first comes decomposition, then regeneration, which symptoms occur rather gratuitously. As a symbol, this transformation mirrors the intermediate stages of enlightenment leading to the victory of man's spiritual nature over his animality. Then the cause of life is profoundly changed.

In folk annals, the spiritual metamorphosis was equated with the changing of the caterpillar into the pupa, which, in its turn, was mysteriously transformed into the butterfly. The imago of the scarab beetle served the same purpose in the land of the pharaohs. In the final analysis, nothing is new under the moon. Yet each new phase of time seeks fresh garments for the ideas that have ever been animating human consciousness guarding it against sensual desires characteristic for the caterpillar’s universe.

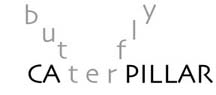

Rethinking our concepts in sculptural form, we tried to fuse two different layers of reality, the immediate physical and the intangible metaphysical, into a single workable organon. That is what we envisioned behind the tri-fold screen of Magic Square Apple.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Magic Square Apple © 1993, C-prints in metal construction |

The magic square is the most legendary numerological concept that puzzles with its marvelous arrangement of numbers. They stand to each other in a perfect harmony embedded in the very concept of mathematical beauty – the sum of any three numbers in a row (horizontal, vertical, or diagonal) adds up to 15. There are magic squares and magic cubes of different orders, but the smallest of them, the order of three, is the most classic example of number symbolism. It found its application in many philosophical schools of the past that coded the laws of nature by abstract numbers, each of them having both a mathematical and an esoteric property. The Ancient Chinese saw behind it a concept of the physical universe, envisioned as an immense magic-square arrangement of innumerable contrasting forces. On our photograph, it is carved on the real apple. The magic of that square is conveyed through the fruit of paradise, which magical properties are no less known in mythology than that of the square. Having attributes of both the cause and the effect of “the fall,” as we know it from the Scriptures, the apple is also a symbol of knowledge (at least in the Gnostic sense), and as such is the closest relative to the intellectual magic square, except that the apple pertains to the world of tangible and gustatory senses.

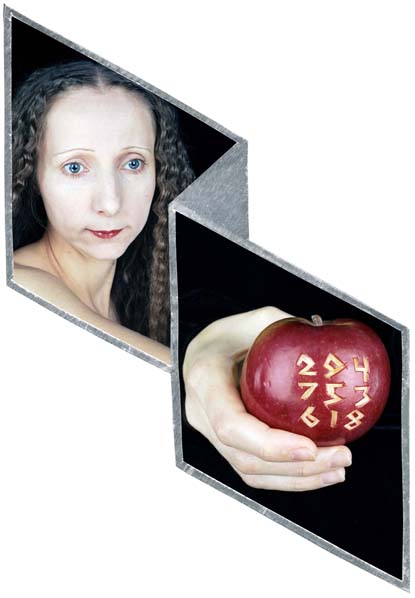

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Revival © 2008, C-print in metal construction |

In general, all metal reliefs enhance the illusory impact of photography. As it is expected, the influence is mutual: the metal sculptures featuring numinous squares obtain another type of magic – the magic of the human presence. The half-opened box of the work Revival is also some sort of a chrysalis or rather a bud from which a new life emerges flashing as a plant in the spring. Mixing poetic and prosaic language, the work depicts a state when one lets go the need to control and just allows things to happen as with plant life. The ability to let go is a clue to the flowering of the intuitive faculties and tuning spontaneity with a conscious way of doing it. As physical and metaphysical necessity can contradict each other, the mind often expresses itself in antitheses. Therefore, it is quite natural that one is transferred to the outer world via internal self-expending space. The path of return lies within.

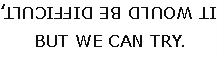

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Prayer © 1993/2009, C-prints in aluminum construction, 35 ½ x 52 ¾" |

Featuring a bowing figure clad in haircloth, Prayer seems to be folded in silence. Absorbed in prayer, the figure is subtle and thin like folded paper, almost bodiless. One fills all the emptiness so as to leave no room for anything else, maintaining the silence of words, desires, and thoughts. In the hierarchy of creation, all things pray except the First, to use an antiquated allegory. Putting in writing any such experience, we would rather use the form of a question than the definite answer.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Second Sight © 1993, C-prints in metal construction |

Plasticity of silence is meant to provide an environment for an alternative vision. In the Second Sight, the “other” eyes are wide open. They are drawn on the half-closed lids of the half-asleep figure, half-wrapped with a wave of hair – all facilitate the atmosphere of awareness in some obscure way, pending on intuition. There is a slight tint of situational irony between apparent and hidden meaning. Yet, it is better not to slay “unfolding” hypotheses by “folded” flat facts. Maybe an intuition is a memory of the truth. Mind and art can only hint at it, but not name it; therefore transformative power will not evaporate. Creative filament is a border between the plasticity of shapes and ideas, perhaps even further, the medium between astral dreams and the solid matter of a mundane life, which are in fact reflections of each other and

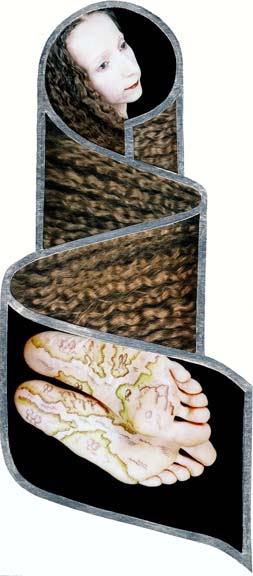

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Unfolding Map © 1993, C-prints in metal construction |

bending of Unfolding Map seems to come into a down to earth cul-de-sac. In simple words, knowledge of the external world is rooted in the experience of the body. How often does man have to bend his mind to the insight that comes from knowledge of gross reality? It carries a weight of inbuilt inertia. Hopefully, the head knows what the feet are after and what they “think” about. Earth is mapped on the traveler’s feet while the unfolding conceptual map of reality, rather than of reality itself, is still an implement helpful in world navigation. The path is one, but it has been mapped differently in different parts of the world. In fact, any creed is some kind of a map. Both in theory and in practice, the meaning of up is understandable only in pairing it with down, right with left, and white with black. Accordingly, the image hints on free-flowing adaptability to the above and the below, tentatively unifying things superior and things inferior, the head and the feet, heaven and earth, the abstract world and the world of particular things following the laws of necessity. To find a tangible or visual rendering of such adaptability is as difficult as to nail a shadow to the earth.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Arc © 1993, C-prints in metal construction |

In Genesis, the firmament divided the waters into above and below the ground. Perhaps both of them are relatively safe for the boat that floats without sails and oars, like Noah who was shut up in his Ark and walked by faith alone. The image is made in the mood of relaxed serenity mixed with the sense of alarming dissolution of the boundaries of material reality: “see-lance” prevails, time stands still, and the mind is in “elsewhere.” The boat seems to lead not into this life but rather beyond it. It is as if the depicted state of ease is born of detachment, equanimity, and self-possession, and is no longer in suspense as to what is good or bad. But there is a further point to understand: “necessity is the kingdom of nature, while freedom is the kingdom of grace,” to convey it with Schopenhauer’s words. 2

In the series of Cutouts, the body is represented in absentia by empty space, thus achieving not only a state of weightlessness but also invisibility. In the image Subliminal Child, whose figure is cut out of the photograph, we meant to show him “transparent to transcendence,” to assimilate Karlfried Dürckheim’s expression. The vacant silhouette casts a soft shadow on the wall seen through its outline, thus acquiring three-dimensional yet ephemeral depth.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Subliminal Child © 1995 (in the middle), C-print in stainless steel frame, 46 х 34”, collection of Nasher Museum of Art, Duke University, NC. The silhouette of the child is cut out. |

Beyond the theoretical ideas embedded in these works, it’s worth mentioning how the photographs functioned in the actual world. For example, Subliminal Child and Bark were exhibited once in quite an unusual context, displayed among the original Renaissance paintings on the same perennial theme at the Nasher Museum of Art, Duke University, NC.

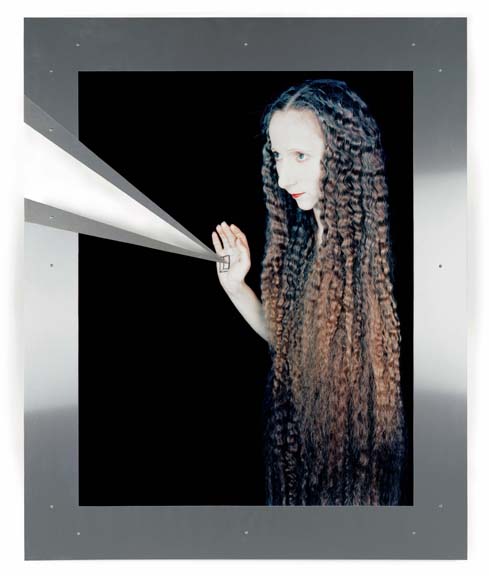

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Slit © 1998/2009, C-print in metal construction, 48 x 39" |

Despite their different shapes, all the cutouts serve the same purpose of rendering intangible elements like air or light, of which Slit is a case in point. Focused on the palm of the hand, the ray of light is created invisibly from the airy emptiness, wedging literally into the physical form of the relief. Light, by which we see, cannot be seen. We see only what it illuminates.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, White Beard © 2008, C-print in metal construction |

Metal scrolls of various types serve us for expressions of unfolding, developing, and disclosing. If in White Beard the theme of androgyny is interwoven with the mystical shroud, the work Windy Scroll lends itself to relatively free interpretation. One work is vertical, while the other is horizontal, yet both are distinctly elongated and blown out of proportion.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Windy Scroll © 2008, C-print in metal construction |

In an attempt to maintain both the flow of the metaphor and the airflow, the image Windy Scroll is made as a visual narration: a whiff of hair is breathing over the horizon, blowing lightly like the wind. There is another Scroll that needs no horizontal or vertical scrolling to see its invisible or unwritten message. Fashioned after a scroll of parchment, the manuscript is permanently rolled.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Scroll © 2004, C-print in metal construction |

The scribe is the image, while the scroll is the reality – it is a metal roll with an invisible message. There are no words; we only refer to them in a relative sense, as something that might engrave itself upon our minds as facts worth remembering and transmitting. The words are different, but the essence is the same, based on ideas well nigh unutterable, in terms of ordinary ways of thinking. Therefore, the scroll is left bare and can take that intuition no further. It is the very hinge of artists not to feel committed to the final conclusion.

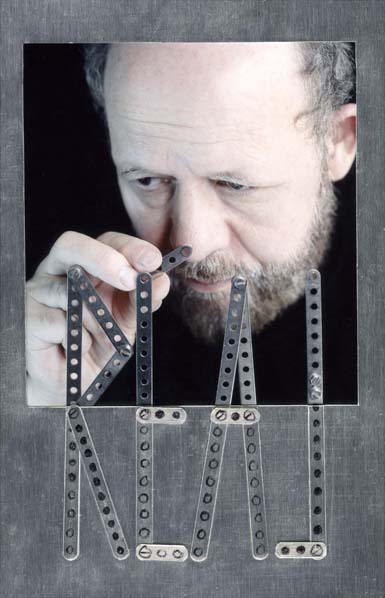

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Real © 2008, C-print in metal construction |

If we try to extract a single word from the unwritten scroll, the relief Real would be a perfect specimen of the conjunction of two realities, the photographic and the sculptural. They go together like an erector set – as indeed it is. The key ingredient of this work is in the syntheses of the real metal relief and its photographic replica, thus extending the flat image into a three-dimensional space. Violating traditional guidelines of photography, that method lends different weights to its otherwise “flatland” regularity, while connecting two levels of reality – imaging and its physical materialization. The letter “L” is written backward, reiterating the same motif that reality is self-similar. Were we to go on conceptualizing reality, then these ideas would move into a dimension of the unreality of things.

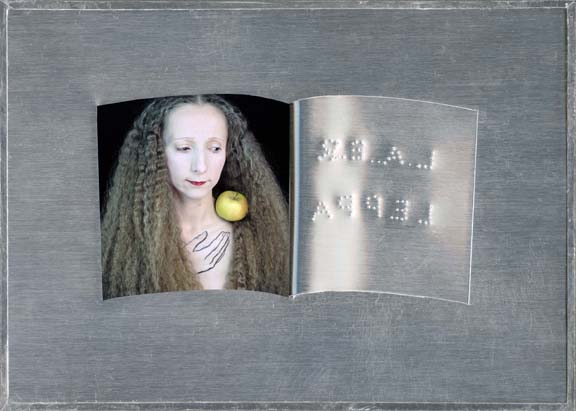

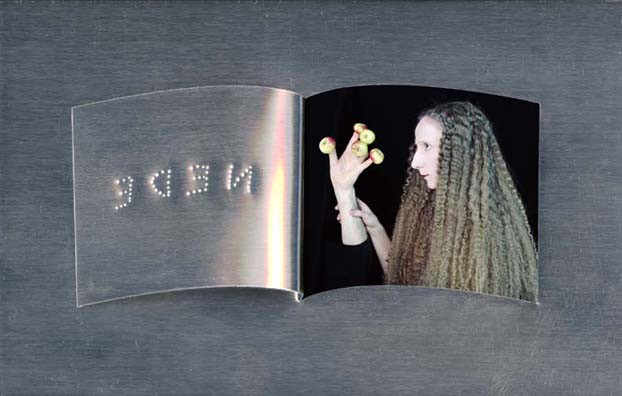

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Real Apple © 2005, C-print in metal construction |

In the same manner, the opened window of the relief Real Apple is engraved with the backward written title. The apple is real, while the stretching out hand is just a skin-deep drawing, merely a desire. In hankering after the world, man feeds upon what he has created in his mind, often consuming himself while trying to pursue it. The image is focused not only on the object of desire, the fruit of action, but mainly on the intention – the desire itself, which seems to be that very “stuff that dreams are made on.” 3 Giving consent to desire, we breathe them to give breath to our life. As a new yearning secedes a phase of fulfillment, one wants not an apple but an entire apple tree, then an orchard, and the Boschian Garden of the Earthly Delights,4 which is also a picture of Eden, but an inverted one.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Eden © 2005, C-print in metal construction |

The tree of life is rooted in a thirst for life. Under its shade, an ordinary man spends his entire life in the pursuit of objects of desire, being led through the world by his own craving. Both his destiny and his character are the sum total of his desires that are the moving force behind his karma. But who can claim that his heart is entirely unsullied by some longing, hopes, and fears? Does “desire only burn in order to burn itself out,” as C. G. Yung described it? 5 Every process of growth needs an open window, some air holes, through which atemporal ideas can enter into the temporal world. Therefore, in the universal spiritual tradition, the path of the so-called “immortals” was the path of return and subsequently included control over deeds, words, and desires.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Trefoil © 2005, C-print in metal construction |

The boundaries of the world of matter and the fields of consciousness are arbitrary. Certainly, there has to be a door between the two hemispheres. The third hand, pictured in the photograph, symbolizes an impulse not our own hence it appears at its own time, not ours. Coming as an animated movement of spirit, it is not superimposed as a sovereign power over natural events, but revealed through some kind of an opening if the disposition for the reception is evident. The moment when the psychosomatic “chaos” is reduced and the mind does not wander, a fresh pair of eyes might uncover something new. Open-mindedness is limitless if it is able to stay open. Trefoil knot expresses the union of the recollected energies and forces, not limited by an individual projection of what reality should or should not be. Physical reality is a consequence of spiritual reality that is not limited by space and time. Perhaps, even more so: espousing a radical view, Jacob Boehme translated his visual experiences into a theological concept: ”God is nearer to man than his bestial body.” 6 Far from the mood of austere rectitude, we try to produce a contemplative art with a simple presence, figuring out what happens, not knowing how; landing right, not knowing how we got there. Art is an attempt to step outside time.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Tetraktys © 1989/2006, C-print in metal construction |

Another form of an opening, the numerological one, is depicted in the relief Tetraktys. Depicting the pattern from one to ten, the tetraktys (from tetras, “four” in Greek) is a symbolic paradigm of creation:

the ten - et

of antiquity resting on its

La -ten -t po - ten -tial

The crowning ten is a turning point of all counting, returning to the completeness and unity of one but on a higher octave. The sum of the lowest row is also ten (1+2+3+4=10). The tetraktys was revered by the cultivated Hellenes not less than the icons by the Orthodox Christians or the mandalas by the Buddhists. It develops through the sequence and the relationships of odd numbers, called “positive and active,” and even numbers, “negative and passive.” (That property of the tetraktys were dimly reflected in the black and white columns of the Tree of Life in Kabbalah and in Freemasonry.) In the mind of the Pythagoreans, whose neophytes took their oath upon the tetraktys, it was a reconciliation of the notions of unity and diversity.

The human element imparts a familiar, viable quality to abstract mathematical ideas that in themselves possess supreme austere beauty that talks mainly to mind and not descends to the level of feelings. Perhaps it needs to have “a face” to be perceptible. In the relief with the “unwrapping” Tetraktys, we tried to summarize everything of importance within the human forms, seeing a man as a temple and a temple as a man. The validity of the tetraktys is not only in the abstract veracity. To a certain degree, it represents a numerological “drama” of creation that includes all psychological factors of life, both a destiny of humanity and a single individual. Inscribed right on the nose, the tetraktys looks like a building block or rather as a human megalith, preserving both the macro and the micro connotations.

| Valeriy Gerlovin, Tetraktys 1987, aluminum, 45 х 46 х 6” |

In spite of an abstract appearance, the numbers convey and code the same principles of energy, ascribed to different deities and the angelic hierarchy. Each of these powers has its own enveloping aura or, in physicists' term, its own electromagnetic field. The fractal geometry and musical harmony (scales, keys, octaves, etc.) are also based on the concept of the tetraktys. It symbolized a hierarchical stepladder going in both directions, upstairs and downstairs, therefore for the ancients it was not a merely intellectual concept – it represented an entire mystery behind the progression of the soul.

In the context of our conceptual art, behind all these numerological exegeses there are both the art of Orpheus and the science of Pythagoras, in other words, the creative metaphors and the number symbolism, to which intersection that relief belongs. Our fascination with this subject and, perhaps, understanding of it were not a product of reading that furnishes one mostly with facts. We integrated these ideas via our creativity. In words of Heinrich Zimmer, “The best things can’t be said; the second best are misunderstood; and we are using the third best, the conversation, in order to talk about the first and the second best.” 7

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Pyramid in Cube © 2008, C-prints in metal construction |

Undoubtedly, there is a connection between the Greek tetraktys and the Egyptian pyramid. Hypothetically, we might envision it positioning the magic square on its bottom and four tetraktyses on its sides. If the “bottomless” magic square entwines the ethereal and the physical within its dense gravity, the tetraktys represents the dynamic paradigm of the ascending and descending energy. The photorelief Pyramid in Cube visually touches upon that idea, leaving aside the metaphysics. It is not our intention to minutely describe our Flat Solids based on our heretically understood mathematical properties, but some of them, such as spheres and various oval forms, deserve an attention. Therefore, elliptically speaking, our next chapter develops around the circle.