|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rimma Gerlovina, Valeriy Gerlovin, Be-lie-ve © 1990 |

by Gigliola Foschi |

|||||

“Tendiamo a seguire i nostri sentimenti,

non i nostri istinti; seguiamo la mente, non i sentimenti; lʼintuizione,

non la mente. Fra una marea di meraviglie, si tratta del processo di

trovare lʼarticolazione dellʼanima.”– Un poʼ misteriosi, quasi esoterici,

Rimma Gerlovina e Valeriy Gerlovin ci raccontano così il loro ultimo

lavoro Perhappiness, in cui le parole perhaps (“forse”) e happiness (“felicità”)

sono contraddittoriamente intrecciate. Nate allʼinsegna del paradosso,

le opere di questi due artisti sono davvero difficili da definire, anche

perché i Gerlovin nel corso degli anni sono passati dallʼinstallazione

alla performance, dalla poesia visiva alla fotografia. La loro stessa vita è allʼinsegna del cambiamento: dopo aver fatto parte, negli anni Settanta, delle avanguardie moscovite dellʼarte underground, nel 1980 i due artisti lasciano il mondo repressivo della Russia Sovietica per vivere negli Stati Uniti. Ben accolti dal mondo artistico occidentale, i loro lavori vengono immediatamente esposti in numerosi musei, come lʼArt Institute of Chicago, il New Orleans Museum of Art, il Tel Aviv Museum of Art, il Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography e altri ancora. In America realizzano numerose sculture, ma soprattutto si concentrano su una serie di opere fotografiche che chiamano photoglyphs (letteralmente “incisione con la luce”, dal greco phos- photós “luce”, e glyphé “incidere”) dove utilizzano soprattutto primi piani ravvicinati, con parole e crittografie simili a incisioni, che si ritrovano anche nel loro ultimo lavoro Perhappines. Ambigua e ironica, questʼultima serie di immagini ha quasi sempre per soggetto Rimma Gerlovina, coi suoi lunghi capelli ondulati e serpentiformi, capaci di trasformarsi in elementi inquietanti, seduttivi, penitenziali… “I capelli sono il materiale organico che è spesso più a portata di mano (e di testa). In termini tecnici, è un modo facile, compatto e autosufficiente con cui vestire una donna. Eʼ il vestito più naturale, la più archetipica moda che non va mai fuori moda. Ci serve contemporaneamente sia da pseudo abbigliamento, che come cilicio per la penitenza. Poiché tendiamo a creare lavori basati su concetti atemporali, dobbiamo seguire le loro regole, che richiedono forme mitologiche e metaforiche per manifestarsi”, spiegano i due autori. Il tempo accelerato della realtà contemporanea non è infatti previsto nelle loro immagini, che tutto allʼopposto si propongono come opere emblematiche sospese tra mito e umorismo, misticismo e stravagante simbolismo. Vediamo Rimma tra magiche provette alchemiche, mentre con fare da maga maneggia un uovo (simbolo del seme primordiale, del sole e della luna, nonché viatico dellʼaldilà), o addirittura in versione “testa decollata di san Giovanni Battista” sollevata su un piatto di capelli. |

We tend to follow our feelings, not our instincts; to follow the mind, not feelings; to follow intuition, not the mind. Amidst myriad wonders, it is a process of finding the articulation of the soul.”—somewhat mysterious, almost esoteric, this is how Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin describe their most recent work, “Perhappiness” in which the words “perhaps” and “happiness” are juxtaposed. Born under the sign of paradox, the works of these two artists have ranged from installation to performance, visual poetry and photography. Their very lives have been marked by change. After having been part of the Moscow avant-garde underground art movement in the 1970s, in 1980 these two artists left the repressive world of Soviet Russia to live in the United States. They received a warm welcome from the western art world and their works were immediately shown in numerous museums, including the Art Institute of Chicago, the New Orleans Museum of Art, the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, as well as others. In America they created a number of sculptures, but they concentrated primarily on a series of photographic works they called “photoglyphs” (literally, light etchings, from the Greek “phos-photós” = light and “glyphé” = to etch) in which they used principally close-ups with words and cryptographs similar to etchings, which are also found in their most recent work, “Perhappiness”. Ambiguous and ironic, this latest series of images almost always features Rimma Gerlovina as their subject with her long, wavy, serpentine hair with the ability to be transformed into an unsettling, seductive, penitential element. “Hair is an organic material that is often what is closest at-hand (and on the head). In technical terms, it is an easy, compact and self-sufficient way to dress a woman. It is the most natural clothing, the most archetypical style that never goes out of fashion. We can use it both as a type of pseudo-clothing as well as a hair shirt for penitence. Because we tend to create works based on a-temporal concepts, we have to follow their rules that require mythological and metaphorical forms to be seen,” these two artists explain. The fast-paced rhythms of contemporary life are not part of their images which, on the contrary, appear as emblematic works suspended between myth and humor, or mysticism and eccentric symbolism. In one image we find Rimma immersed in alchemistʼs vials as, like a sorceress, she plays with an egg (symbol of the primordial seed, the sun and moon as well as a viaticum for the afterlife), in another portrayed with the head of St. John the Baptist lifted on a plate of hair. |

|

|

||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

Rimma Gerlovina, Valeriy Gerlovin, Flask ©

2001 |

Potete dirci qualcosa di più sui vostri primi

contatti con lʼarte in Russia e sullʼimportanza che il movimento Samizdat

ha avuto nei vostri lavori?

Si è trattato di un periodo individualista. Lʼabbiamo descritto nel nostro primo libro Russian Samizdat Art, uscito nel 1986, sette anni dopo la nostra partenza dalla Russia. A vivere attraverso lʼauto-pubblicazione (in russo samizdat) non fu solo la letteratura: tutta lʼarte sopravvisse in un modo simile. Era una forza automotivata ed autosufficiente. Lʼarte del Samizdat ha probabilmente rappresentato il più simbiotico miscuglio di arte nel movimento underground, una sorta di ibrido di concettualismo, poesia visiva e concreta, libri di artisti, documentazione di performance e installazioni. Sostenuta da una sconosciuta intellighenzia culturale allʼOvest, ha continuato a fermentare nellʼisolato, quasi ermetico, recipiente della Russia Sovietica. La sua costituzione permetteva quasi tutto di diritto, mentre quasi tutto era proibito di fatto. A quellʼepoca lʼesposizione ufficiale dei nostri lavori artistici sarebbe stata impossibile. Invece, noi ed altri amici artisti abbiamo dato vita a mostre non ufficiali, spesso collettive, nei nostri appartamenti. Per un poʼ di tempo abbiamo mantenuto un giorno fisso, un giorno la settimana in cui le nostre abitazioni si aprivano agli amici, che a loro volta portavano altri amici e così via, senza mai interrompere la catena. Eʼ così che la molteplicità delle singole esperienze artistiche, quelle non ufficiali, ha potuto sopravvivere. A casa nostra, abbiamo ospitato diversi poeti, esibizioni musicali, e tanti altri rumorosi eventi come la lettura di poemi musicali di Rimma, rappresentati da cinque esecutori nello stile del madrigale. Tutte queste attività non solo disturbavano enormemente i vicini, ma attiravano periodicamente lʼattenzione della polizia. Qui, come risultato di numerose riunioni tra amici, sono nate molte idee sovversive: ad esempio la preparazione della prima rivista sullʼarte contemporanea russa A-Ya , pubblicata in seguito a Parigi. Quando gli storici dellʼarte europei cominciarono ad “infiltrarsi” nei circoli moscoviti, li aiutammo a raccogliere materiale per il primo articolo sul concettualismo di Mosca per la rivista Flash Art, che creò un legame con la Biennale dellʼEst Europeo a Venezia nel 1977. Durante questa manifestazione, la stampa internazionale notò la nostra performance Zoo (nella quale sedevamo nudi in una gabbia con il cartello “Homo Sapience, group of mammals, male and female” - a simboleggiare la cultura russa ingabbiata dal regime Sovietico. Come era prevedibile, questʼavvenimento focale ci creò numerosi problemi con le autorità, per cui, dopo che i cubi di Rimma furono nuovamente esposti alla biennale successiva, nel 1978, venne il momento di fare fagotto. Come tocco finale, il nostro party dʼaddio fu allegro ed esagerato come quello di Finneganʼs Wake. |

Can you please tell us more about your early

approach to the Arts in Russia and the importance that the Russian

Samizdat Movement had on your works?

It was a maverick period. We described it in our early book Russian Samizdat Art that appeared in 1986, seven years after our departure from Russia. Not only literature had to live by self-publishing (samizdat in Russian),but art also survived in a similar manner. It was a self-motivated, self-sufficient force. Samizdat art represented probably the most symbiotic potpourri of art in the underground movement, sort of a hybrid of conceptualism, visual and concrete poetry, artistsʼ books, documentation of performances and installations. Supported by the unknown unity of cultural intelligentsia in the West, it continued to brew in the isolated, almost hermetic, vessel of Soviet Russia. Its constitution permitted almost everything de jure while almost everything was forbidden de facto. In this period, official exhibition of our artwork would have been impossible. Instead, we and other fellow-artists thrived on unofficial, usually group, exhibitions in our apartments. For some time we had a jour fix, a one-day-a-week open apartment for friends, who used to bring their friends and so on, thus keeping the chain unbroken. That was how self-preservation of the collective singularity common to the unofficial multiplex of Russian culture was built. In our own place, we held many readings of different poets, musical performances, and other noisy events like reading Rimmaʼs score-poems by five performers in a manner of madrigals. All this activity not only greatly disturbed our neighbors, but periodically attracted the attention of the police. Here, as a result of many gatherings with our friends, many subversive ideas were born: for example, preparation of the first magazine on contemporary Russian art A-Ya that was later published in Paris. When European art historians began to ʻinfiltrateʼ into Moscow art circles, we helped them to collect material for the first article on Moscow conceptualism for Flash Art magazine that created a link to the Eastern European Biennial in Venice in 1977. During this event, the international press picked up our performance Zoo (in which we were seated naked in a cage labeled ʻHomo Sapience, group of mammals, male and femaleʼ) symbolizing Russian culture caged by the Soviet regime. As could be expected, this focal event created many problems for us with the authorities, therefore, after Rimmaʼs cubes were shown again at the next international Biennial in 1978, the time came to pack up our belongings. As a final touch, our seeing-off party was as merry and wild as that in Finneganʼs Wake. |

|

|

|

|

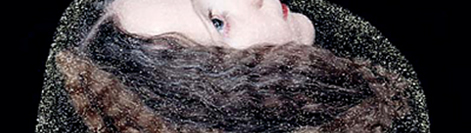

Rimma Gerlovina, Valeriy Gerlovin, Grail © 2001 |

Esiste ancora un circolo di artisti dove

discutete e vi scambiate opinioni? Eʼ ancora importante, per voi?

A New York, il nostro nuovo circolo di amici si costituì molto in fretta. Una felice coincidenza ha portato unʼartista e poetessa visiva italiana, Mirella Bentivoglio, a New York proprio nello stesso periodo del nostro arrivo. (Era stata uno dei curatori della biennale del 1978; è così che ci eravamo conosciuti) Lei ci presentò a diverse persone; e quel circolo crebbe come in una reazione a catena. Forse grazie alla giusta alchimia, la sua amica Jean Brown, collezionista di Dadaismo, Surrealismo e Fluxus, divenne anchʼessa nostra cara amica per diversi anni. E la stessa cosa si può dire di Mirella. Naturalmente, cʼerano innumerevoli discussioni e scambi dʼopinioni nel multilingue mondo artistico di New York. I nostri relativamente piccoli oggetti concettuali, caratteristici del periodo moscovita, divennero grandi progetti scultorei e addirittura murales. Ci tornano in mente i commenti di un critico dʼarte che affermò che quando venne nel nostro loft-garage a Manhattan in Spring Street, si sentì come Alice mentre entra nel buco e subito riappare nel bel mezzo di spettacoli e meraviglie di unʼaltra dimensione. Dallʼaltro lato, è come se assieme alla libertà creativa dellʼOvest, sperimentassimo una sorta di regressione nel caos, dentro lʼeterogeneo mondo dellʼarte. New York è un agglomerato di un poʼ di tutto e di qualsiasi provenienza, in cui tutto è etichettato come normale, anche la cosa più anormale. Qui abbiamo incontrato un individualismo altamente soggettivo, quasi al confine con un atavico egoismo, una frammentazione psicologica e una varietà di altri corto circuiti. Nonostante la caratteristica di ogni singolo individuo, molti ripetono le opinioni di altri, sotto la maschera della libertà artistica. In breve, New York ha stimolato lʼesteriorizzazione delle relazioni a scapito dei valori interiori. Ma, staccandoci dai fatti ed addentrandoci nel mondo delle idee creative, il quadro cambia. Spostarci nello spazio dallʼEst allʼOvest, è stato il preambolo per muoverci nel tempo, dalla giovinezza alla maturità. Entrambi questi cambiamenti implicano degli adattamenti e portano al cosiddetto processo di individuazione, che richiede alcune potature come a separare la paglia dal grano. Le persone camminano al proprio passo, secondo dei cicli, e normalmente le idee non vengono comunicate di getto, ma per gradi. E uno di questi gradi è stato espresso nel nostro passaggio alla fotografia concettuale alla fine degli anni ʼ80. Per questo ci occorreva un altro ambiente, di tipo contemplativo. Le cose possono avere una loro profondità, ma essa nasce dentro di noi, e per ritrovarla occorre concentrazione e molto di più. Come sempre la vita ci faceva succedere le cose in sequenza, così lasciammo Manhattan per spostarci in campagna. Avevamo meno amici, ma più silenzio e concentrazione che aiutavano la nostra creatività. |

Do you still have a close circle of artist

friends where you discuss and share opinions? Is that still important

to you? But stepping aside from the events and entering the world of creative ideas, the picture changes. Moving in space, from the East to the West, was a preamble for our moving in time, from youth to maturity. Both these shifts involve adjustment and lead to the so-called process of individuation that requires some ʻpruningʼ of the environment: separation of the Chaff from the Wheat. People walk at their own speed, in cycles, usually ideas are not communicated at once, but by gradations. And one of those gradations was expressed in our switch to conceptual photography at the end of the 80s. For that we needed another environment, a contemplative one. Things can have depth but that depth is within us, and its recovery needs concentration and much more. As usual, life was acting out the events in sequence, so we moved out of Manhattan to the country. We had fewer friends, but more silence and concentration conducive to our work. |

|

|

|

|

Rimma Gerlovina, Valeriy Gerlovin, Mini

Lab © 2003 |

Rimma, lei è stata definita “poetessa tridimensionale”:

che effetto le fa e quanto è importante la poesia nella creazione

delle sue immagini?

Molti concetti nelle nostre fotografie sono radicati nella poesia tridimensionale. Queste poesie sono di solito “coperte” da piccoli cubi, che presentano un testo allʼinterno o allʼesterno. Sostenendo gli elementi di poesia contenuti nellʼoggetto dʼarte, questi cubi sono come degli haiku che si materializzano; essi parlano col linguaggio della semplicità codificata, dove la chiarezza metaforica non contraddice lʼambiguità. Se si apre il cubo con “My thought” sul coperchio, quale potrebbe essere la risposta al suo interno? Mentre Rimma era versatile soprattutto nei concetti legati alla parola, Valeriy era a proprio agio con le forme archetipe, come se lei impiegasse il metodo algebrico del concettualismo e lui prediligesse quello geometrico. Entrambi questi approcci costituiscono la base per la nostra fotografia. Nella nostra prima serie di Photoglyphs (che significano letteralmente “incisione con la luce”, in greco phos-, photos- significa luce e glyphe sta per “scavare”) abbiamo utilizzato soprattutto primi piani ravvicinati, con parole e disegni crittografici. Sono stati ottenuti direttamente sulla pelle come su una pergamena umana. Abbiamo fotografato le parole “scelte” senza il contesto verbale, scritte sui visi. Estraendo il significato metafisico dal tradizionale ambiente del libro, lʼabbiamo messo direttamente sui visi, spostandolo, diciamo così, nel dominio della verità poetica. In questa nuova ambientazione organica, le parole sono apparse nel pieno del loro significato allusivo e non come i morfemi senza identità della forma testuale lineare. Abbiamo dato loro corpo. Allo stesso tempo, i nostri pensieri divenivano visibili, ricaricati dellʼespressione dei tratti del volto . Per esempio, abbiamo letteralmente sezionato la parola “be-lie-ve” (credete) sulla fronte con lʼaiuto delle trecce. Dimostrando il tradimento della falsità, la parola era costretta a rivelare il suo nucleo contraddittorio. La stessa questione della credibilità della mente messa alla prova nei cubi è apparsa nelle nostre fotografie. Una menzogna può giungere sotto lʼaspetto di una verità, e viceversa la verità sotto forma di menzogna. Cre-dia-te-lo o no. Attraverso le parole, possiamo arrivare ovunque, ma non necessariamente alla verità. Ad esempio, prendiamo le parole del Mullah Nasredin, il maestro Sufi, che disse: “ Io non dico mai la verità”. Provate a capire. Se ciò fosse vero, contraddice la sua stessa affermazione. Ma se mentisse, come promette, significa che sta veramente dicendo la verità. Come è avvenuto il passaggio dalla performance art alle “still performances”? Il motivo delle nostre prime performance celava in termini mitologici ciò che avremmo sperimentato più tardi nel nostro insieme di arte e vita. Eravamo già coinvolti nella messa a punto di un progetto per le nostre future fotografie, quel Photomorgana di illusioni ottiche e di esplorazione attraverso il significato delle parole, dei segni e dei simboli. Ad esempio, una delle nostre prime still performance The Eggs (le uova) del |

Rimma, you have been called a “three-dimensional”

poet, how do you feel about this and how important is poetry in the

creation of your photographs?

Many concepts in our photography are rooted in that three-dimensional poetry. These poems are generally ʻclothedʼ in small cubes, which have text inside or outside. Bearing the elements of poetry set up within the object of art, these cubes are like materialized haiku; they speak with the language of coded simplicity, where metaphorical clarity does not contradict the ambiguity. If one opens the cube with ”My thought” on the lid, what would be the answer to its inward question?and much more. As usual, life was acting out the events in sequence, so we moved out of Manhattan to the country. We had fewer friends, but more silence and concentration conducive to our work. Rimma, you have been called a “three-dimensional” poet, how do you feel about this and how important is poetry in the creation of your photographs? Many concepts in our photography are rooted in that three-dimensional poetry. These poems are generally ʻclothedʼ in small cubes, which have text inside or outside. Bearing the elements of poetry set up within the object of art, these cubes are like materialized haiku; they speak with the language of coded simplicity, where metaphorical clarity does not contradict the ambiguity. If one opens the cube with ”My thought” on the lid, what would be the answer to its inward question? While Rimma was versatile predominantly with the word-concepts, Valeriy was at home with archetypal forms, as if she employed the algebraic method of conceptualism, while he preferred the geometrical one. Both these approaches constituted the basis for our photography. In our early series of Photoglyphs (which literally means ʻcarving with lightʼ, in Greek phos-, photos- denotes ʻlightʼ and glyphe stands for ʻcarvingʼ) we used mainly close-ups, with cryptographic words and drawings. They were made directly on the skin, like on a human parchment. We photographed the ʻchosenʼ words without verbal context, inscribed on the faces. Extracting the metaphysical meaning from the traditional bookish environment, we placed it straight on the faces, moving it into, say, the realm of poetic truth. In that new organic environment, words appeared in the full body of their allusive meaning, not as faceless morphemes of the linear textual form. We gave them flesh. At the same time, our own thoughts became visible, recharged with the expression of the features of the faces. For example, we literally dissected the word ʻbe-lie-veʼ on the forehead with the help of the braids. By demonstrating the treason of falsity, the word was forced to reveal its contradictory core. The same question of reliability of mind tested in the cubes appeared on our photographs. A lie can come in the form of a truth, and the truth can come in a form of a lie. Be-lie-ve it or not. By words, we can arrive anywhere, but it is not necessarily at the truth. For example, take the words of Mullah Nasredin, the Sufi master, who said: ”I never tell the truth.” Try to grasp it. If this is true, it contradicts his statement. But if he lies, as he promises, it means he really is telling the truth. |

|

|

|

Rimma

Gerlovina |

1977, si sviluppa in tre fasi: la prima illustra i

nostri corpi in posizione fetale allʼinterno di due uova; poi stiamo

friggendo queste uova, mentre nella terza foto stiamo mangiando queste

uova come pasto auto-sacrificale. Finalmente si mangia.

Questa performance è stata allestita come un ritornello, apparentemente tornando allo stato iniziale, ma ad un ottava più alta. Era come un serpente ouroboro, che si mangia la sua stessa coda, e cosi ricrea se stesso. Più tardi il tema dellʼembrione, delle uova e degli elementi sacrificali riapparvero in molte nuove forme nelle nostre fotografie. Non esiste un confine netto tra le foto in bianco e nero delle nostre prime performance e il lavoro successivo. La differenza è che allora avevamo degli spettatori e invitavamo diversi fotografi, mentre ora siamo noi stessi a fotografare lontano dalla vista del pubblico. Cʼè stato un momento in cui ci siamo fermati (per quanto riguarda le sculture) per trovare nuove idee. In ogni caso le nostre performance, allora come adesso, sono ugualmente delle still performances. Le vostre fotografie sono come gemme; ognuna è davvero speciale. Cosa significano veramente per voi? Sembra che durante tutti questi anni abbiamo sviluppato il nostro discorso fotografico alla maniera di un sutra. Nel processo del suo stesso divenire, porta con sè un filo concettuale che lega |

How did the transition from performance art to “still performances” happen?

The motives of our early performances concealed in the mythological terms what we were supposed to experience later in our art-and-life complex. We were already involved in creating a blue print for our future photographs, that photomorgana of optical illusions and explorations by means of words, signs, and symbols. For example, our early still performance The Eggs, 1977, develops in three stages: the first one depicts two eggs with our bodies in the embryonic position inside them; then we are frying these eggs; and in the third picture we are eating these eggs as the self-sacrificial meal. Supper at last. This performance was enacted in a ritornello manner, seemingly returning to the initial state, but in the higher octave. It was like an ouroboros snake, eating its own tail, and thus recreating itself through its own known substance. Later the theme of embryos, eggs, and sacrificial elements reappeared in many new forms in our photography. There is no sharp border between the black-and-white photographs of our early performances and the later work. The difference is that then we had spectators and invited different photographers, now we shoot ourselves and out of the public view. There was a moment when we stopped (for sculptures) to regain new breath. However, our performances, then and now, are equally still performances. |

|

|

|

|

Rimma Gerlovina, Valeriy Gerlovin, Large

Print © 2000 |

assieme i suoi grani come un rosario (che è lʼesatto

significato di sutra in Sanscrito). Alcune persone

conoscono ed osservano se stesse solo in un flusso costante di sviluppo,

sia esso un processo

interno oppure esterno. Questo lavoro, prima di ogni altra cosa, sfrutta le risorse della conoscenza, che è forse in grado di illuminare i punti interni di contatto. Forse è un esercizio necessario per lʼanima. Lʼarte moderna pone lʼattenzione principalmente su realtà decostruttive e su istinti primari, nutrendosi abbondantemente degli impulsi originati dallʼego dellʼartista. Vivere per lʼarte e vivere di arte è una cosa ben diversa. Con lʼaiuto dellʼimmaginazione, il viaggio verso il mondo intelligibile può riparare ciò che è stato rotto da una visione distorta e conflittuale della quotidianeità. Può portare gli archetipi in una dimensione temporale. Ed evocare lʼintuizione. Lʼintuizione, se messa al di sopra dellʼintelletto, porta con sè un effetto olistico. Uno degli strumenti importanti in grado di creare quelle che voi chiamate “gemme” è nascosto tra le pieghe dellʼumorismo, che accompagna molti dei nostri concetti. Uno scherzo impercettibile, verbale o visivo, può aiutare a risolvere i paradossi nascosti dentro i limiti della vita. Di fatto, la vita umana è piena di zig zag, che spesso si uniformano attraverso una serie di contraddizioni. Per controbilanciare questa verità, noi cerchiamo di unire lʼessenza col nonsenso, con lʼaiuto del buon senso. Nonostante le vostre immagini siano visivamente molto sofisticate, ho letto che voi non usate la manipolazione digitale. Come le realizzate? Utilizziamo una fotocamera 4x5” che ci offre innumerevoli possibilità di esposizi esposizioni multiple. Tracciamo uno schizzo della prima esposizione sul vetro di messa a fuoco ed esponiamo la seconda immagine sullo stesso negativo col massimo della precisione. Il procedimento richiede una certa disciplina e una concentrazione che può essere paragonata a quella richiesta ad un arciere. Cercando di ottenere unʼimmagine che sia il più vicino possibile a come lʼabbiamo immaginata, rendiamo praticamente irrisoria la necessità di ritagliare, ritoccare e manipolare durante il processo di stampa. Le fotografie sono basate su schizzi e, tuttavia, sono create dʼimpulso. Guardando indietro comprendiamo che tutti gli sforzi di una vita dedicata allʼarte in generale e alla fotografia in particolare sono stati piuttosto spontanei e in un certo senso naturali. Attualmente, realizziamo solo stampe a colori e utilizziamo Photoshop principalmente per il design, la poesia visiva e le correzioni tecniche delle scansioni. Un giorno potremmo usarlo anche per scopi creativi. Non ci piace ricorrere ad assistenti perché abbiamo lʼimpressione che il nostro lavoro si sviluppi come in un processo alchemico, senza testimoni e senza influenze dallʼesterno. La musica barocca, più spesso quella di J.S. Bach, ci fa da sottofondo mentre lavoriamo. Ci aiuta ad organizzare le idee sui nostri volti come un dramma lirico o un sermone si adattano alla musica. Per quanto invece attiene agli sfondi, noi prediligiamo il velluto nero che si adatta bene a ricreare scene di vuoto contemplativo e di incertezza sulla collocazione geografica e temporale. Questo nero senza colore e senza fondo fa levitare la scena dalla monotonia del mondo, trattenendo solo lʼessenziale. Per molti la nullità dello sfondo è inconcepibile. Noi la pensiamo diversamente: la vera pienezza non può essere veramente piena se non include in sè anche il concetto di vuoto. I capelli di Rimma suggeriscono una grande forza, polivalente e significativa nelle vostre immagini. Perché i capelli sopra ogni altra cosa? I capelli sono il materiale organico che è spesso più a portata di mano (e di testa). In termini tecnici, è un modo facile, compatto ed autosufficiente con cui vestire una donna. Eʼ il vestito più naturale, la più archetipica moda che non va mai fuori moda. Ci serve contemporaneamente sia da pseudo abbigliamento che come cilicio per la penitenza. Con questi creiamo oggetti come il Graal e tessiamo disegni lineari coi boccoli come nella Eva a figura intera. Siccome siamo inclini ad un lavoro basato su idee atemporali, dobbiamo seguire le loro regole, che richiedono simili forme mitologiche e metaforiche per manifestarsi. La cosa più importante è che la struttura filamentosa dei capelli chiari ci permette di creare la minima densità corporea, esaltando, così in una certa misura, il principio della consapevolezza. Eʼ difficile trovare unʼespressione adeguata in una forma tangibile, che possa mostrarci una sostanza intangibile. In generale, i pensieri inafferabili hanno la tendenza ad attrarre una corrispondente visione meno densa della figura umana. Sotto questo aspetto, la ricerca estetica (nel suo significato, dal greco, di senso di percezione) aggiunge qualcosa a quellʼidea. Nei sentimenti culturali e religiosi che caratterizzarono lʼarte antica, il lato caritatevole della realtà era mostrato sotto lʼaspetto delle qualità armoniose in cui lʼapparenza fisica non doveva mettere in ombra lʼaspetto metafisico. A Socrate è attribuita la preghiera di donargli la bellezza interiore dellʼanima e concedere che gli aspetti interiori e quelli esteriori di un uomo siano una cosa sola. |

Your photographs are like gems—each one is really

special, What do they really signify for you? One of the important devices for creating

these, as you called them, ʻgemsʼ is hidden in the element of humor,

which accompanies many of our concepts. A subtle joke—verbal or visual—might

help resolve the paradoxes hidden behind the limitations of life. Indeed,

human life is full of zigzags, often conforming to one another through

series of contradictions. To counterpoise this truth, we try to unite

essence with nonsense with the help of the sense. |

|

|

|

|

Rimma Gerlovina, Valeriy Gerlovin, Scholar © 2005 |

Gli oggetti e i simboli che utilizzate nelle vostre immagini sono tratti

da una specifica fonte iconografica o nascono alla vostra sensibilità

personale e al vostro mondo interiore? |

Are the objects and symbols you use in your

images taken from a specific iconographic source or do they come from your own personal sensibility and

inner world? Overall, subtle thoughts have a tendency

to attract a correspondingly less-dense vision of the human figure.

In that respect, the aesthetic quest (and what is aesthetic—in Greek,

a sense of perception) adds more to that idea. In the cultural and

religious feelings that characterized the early arts, the benevolent

side of reality was shown under the aspect of harmonious qualities

in which physical appearance was not supposed to overshadow the metaphysical

aspect. Socrates is credited with the prayer to give him beauty in

the inward soul, and to grant him that the outer and inner aspects

of man be at one. |

Герловины Концептуализм Римма Герловина и Валерий Герловин |