RIMMA GERLOVINA AND VALERIY GERLOVIN

Interview by Russell Joslin

Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin have written, "Light does not exist without shade. Unity comes in a fusion of duality... We regard art as an organic union of interrelated parts whose balance, as in any living organism, is important to maintain." The Gerlovins, who began their artistic collaboration and partnership in Soviet Russia during the 70's, exemplify this idea in their own lives and work. They share backgrounds in performance, conceptual sculpture, and visual poetry--all of which they eventually integrated into their work when they later arrived at photography in the mid-80's. Photographically, the Gerlovins have produced two notable and specific bodies of work, Photogyphs and Perhappiness, both of which are rich in metaphor, language, mythology, and symbolism.

(Note: Remaining consistent with their thoughts on the nature of duality, the quotes in this interview are not attributed to Rimma or Valeriy separately. The Gerlovins explain, "Our minds are twined, therefore, our answers will represent both of us.")

How did you meet, and at what

point did you begin to collaborate on art together?

Our mutual friend invited Rimma to visit Valeriy's studio. Valeriy suggested

to Rimma that he paint her portrait. A year later, we became married.

In two years, we began to collaborate. The four-fold process was quick;

it worked on and produced effect after effect.

Tell me about the Samizdat art

movement that you were a part of. Also, what was the political climate

in Russia like at that time, and how did it affect artists?

"Samizdat" means self-publishing. In earlier days, it was a forbidden fruit

in Soviet Russia; which had a big crop of such fruits in the dissident movement.

If you refract the rays of this underground activity through the prism of art,

the result can be described as a hybrid of conceptual art, visual and concrete

poetry, artists' books, performance art and so on. It was not an imitation

of the West. It was something that was brewing out in the isolated, almost

hermetic, vessel of Soviet Russia. Its constitution permitted almost everything de

jure and forbade almost everything de facto. That was our beginning.

Probably the visual language of our art

will give you the better picture. Hypothetically, our situation could

be symbolized by Rimma's early cubic poem Quintessence, 1974.

|

|

"Above me" is written on the inside lid, "in front

of me" (on each side),

"below me" (on the bottom). The box is empty, or rather it looks empty.

An invisible quintessence of the four elements (the four orientations)

comes as a voice echoed on the walls of the cube. The talking self is in

the middle. The hidden creative force of an individual is literally blocked.

In this period, the official exhibition of our conceptual work would have been impossible. Instead, we and other fellow-artists thrived on the unofficial, usually group, exhibitions in our apartments. For the moment, it was a sort of underground institution, which was constantly in conflict with the authorities. In our own apartment, we held many readings of now famous Russian poets. The periodical musical performances greatly disturbed our neighbors. Here, as a result of many gatherings with our friends, many subversive ideas were born: for example, a preparation of the first magazine on contemporary Russian art A-Ya that was later published in Paris.

If the previously mentioned cubic poem

is an abstract concept of our 'incubated' life in Soviet Russia, the

psychological picture might be envisioned in our performance Zoo.

Homo Sapiens, 1977, (photo by Victor Novatsky).

When we were living

in Moscow, our works were frequently smuggled abroad. Our conceptual

pieces passed for toys, our documentation of the performances for snapshots,

which were then blown up into mural prints for exhibitions. During the

Eastern European Biennial, in Venice, Italy in 1977, the international

press picked up this Zoo image as a symbol of the Russian art

caged by the Soviet regime. As you can expect, this focal event created

for us many problems with the authorities that consequently led to the

emigration.

Now that over 25 years have passed, do you think of this time differently than you did then?

Looking back, we understand that political

and cultural interpretation of this performance presented only half of

the truth; our meaning was more ambiguous. Within the tradition of non-conformism

in general, not only in politically oppressed countries, it hints at

the emergence and the preservation of freedom within the world of necessity.

It is incumbent on the artist to use their freedom to test the limits

of his/her own marginality. The cage imprisons and, if it is taken wisely,

it might protect, in the manner of a cocoon during the metamorphosis

of a caterpillar into a butterfly. Metaphorically, our cage protected

us not only in our motherland of vapid propaganda, but here too, in the

country of monetary hegemony.

|

|

Artists with their works in Moscow.

We described our 'prenatal' creative response to those evolutionary events, and the vistas of youth in our early book, Russian Samizdat Art (Willis, Locker, and Owens, New York, 1986). This book appeared seven years after our departure from Russia, and summarized our transevolutionary navigation from the East to the West.

In 1980, you moved to the U.S. What

brought you here?

Spontaneity. On the other hand, we have chosen the country that newspaper Pravda

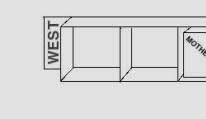

(which means 'truth') criticized most. Again, the visual composition

with the inserted free moving cube, titled Motherland, seemed

to be aiming at the heart of the problem.

For us a "motherland" is

not only a stationary place, it is a process in itself. The Ancient Romans

aptly expressed it in their proverb, Omnia mea mecum porto,

which means, "All that is mine, I carry with me."

Tell me more about your backgrounds

in other mediums, and how photography emerged as your medium of choice.

Sometimes as soon as the accumulation of creative projects reaches its

fulfillment, it bursts into another form of manifestation. At least it

happened to us. Towards the middle of the Eighties, the nucleus of our

art creation in three-dimensional objects was formed, and therefore ready

for revision, expansion, and rejuvenation. This proceeding, which appeared

quite natural from our perspective, was an act of incomprehensible prophetic

necessity, rather than an individualistic search for new directions.

Instead of the ideas of sculptures and objects in our minds and their

actual realizations in physical space, metaphorical photographs emerged

from the seeds of our early performances, conceptual objects, and visual

poetry. Everything evolved from this continuous underground creative

flow, and appeared in new sublimated forms.

|

Sculptures by Valeriy Gerlovin (left) and Rimma (right) at The Fine Arts Museum of Long Island, NY 1991

What would you say are each other's

strengths in terms of your collaboration? Or, in other words,

what do you feel each of you brings to the process of your creations?

Since we both made separate conceptual objects, our joint work reflects

both styles. Rimma's humanoid constructions and shifting objects were

always connected with the language, (like three-dimensional poetry).

In the wooden and metal reliefs made by Valeriy, sculptural elements

predominated. If conceptual ideas and initial sketches for our photographic

series have come from Rimma's side, the visual form was a prerogative

of Valeriy. He had explored strange close-up intensity, some time before

we came to photograph it, namely in the series of murals, paintings,

and sculptures called Ancient New York Mosaics. One such installation

was made in Pittsburgh in 1984, in the vast space of The Mattress Factory,

which is now a museum of contemporary art. In this installation, the

video was mounted in the eyes of gigantic heads that were painted straight

on the walls.

|

|

Explain how

you work as a couple. Are there certain roles that each of you tends

to take on in your work?

We work together and separately, it seems we are one another. In photography,

we formulated this answer in the form of a question, "Am I me?" The factor

of the male/female union contributes much. Fused into a joint 'receptacle'

for the phenomenal world, it naturally increases the outcome. The union

of opposites tends to produce something new--it begets. Therefore, the

creative imagination of both of us synthesized ideas from different realms;

it nurtured a new aesthetical offspring within ourselves. With the mixed

blessing, the physical body of our photographs came from the male side,

or from his hands; from her, came the idea, namely, the concepts, she infused

the spirit.

Will

you tell me more about the series of photographs that you called Photoglyphs,

which involved the use of words and symbols usually applied directly

to your skin?

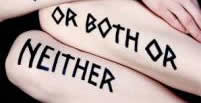

We began this series at the end of the Eighties. Photoglyphs literally

means 'carving with light' (in Greek phos-, photos- denotes 'light'

and glyphe - standsfor 'carving'). These were mainly close-ups,

with cryptographic words and drawings made directly on the skin, usually

on the faces. We photographed the 'chosen' words without verbal context,

sketched on the faces among the eyes and the brows, up on the forehead

and down on the neck. In such a new

environment, words appeared in the full body of their allusive meaning,

not as faceless morphemes of the linear textual narration. We gave them

flesh. At the same time, our own thoughts became visible, recharged with

the expression of the features of the faces. In Acts of John,

one of the early apocrypha,there is a poetic passage about the torment

of a Word, the piercing of a Word, the blood of a Word, the passion of

a Word.

|

|

|

|

|

Believe ¿ 1990 |

When word becomes flesh, it is possible to treat or mistreat it as a body.

For example, we literally dissected the word be-lie-ve on the frontal

place with the help of the braids. By demonstrating the treason of

falsity, the word was forced to reveal its contradictory core. A lie

can come in the form of a truth, and the truth can come in a form of

a lie. Believe it or not. By words, we can arrive anywhere, but it

is not necessarily at the truth.

Do you feel there are specific

connotations of having skin as the most common surface for the words

and symbols you use in your images?

Yes, we have this feeling. It looks like a collection of visual formulas,

inscribed on the skin, which is used as a human parchment. We placed

this curious organic metaphysics, not within the traditional bookish

environment, but straight on the faces, moving it into, say, the realm

of poetic truth. It leaves room for multiple explanations. Maybe this

will be a fair enough analogy: it is similar to a chemist who employs

tinctures and flasks for the experiment; we used our minds as solutions

and our faces as vessels.

|

||

|

To Be ¿ 1989 |

You've

said that your photographs are not portraits? Why not?

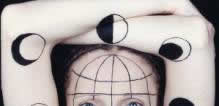

Indeed, they are not. We photograph not the models, but modules. They

happen to be expressed through our faces. Metaphorically, they personify

different stages of psychological and visionary experience. The roles

of the observers and the observed are extended into the unifying state

of being the observatory itself. In technical terms, this method is convenient,

compact, and self-sufficient.

|

|

| Lunation ¿ 1990 |  |

Creativity in general is an extension of the inner qualities of an artist, whose face is the face of the world, expressed through his/her face and dimension. Involuntarily, we exist in all that exists. Therefore, instead of photographing all that exists, we photograph its representations. In short, we express the meaning through our faces; other artists use other media.

|

||

|

Bird ¿ 1989 |

Rimma's hair is oftentimes prominently used in your photographs, and seems to be used in a symbolic way. Do you agree, and if so, what does it symbolize for you?

We use the material that happens to be near at hand (and on the head). Considering the authoritative promise, "The very hairs on our heads are all numbered," we employ this organic fiber as a constructive material in our photographs. It is the most natural primordial outfit of a woman, the most archetypal fashion that never goes out of fashion.

|

||

| Madonna with Child ¿ 1992 |  |

Since we have an inclination to work with atemporal ideas, we have to follow their rules, which demand similar mythological and metaphorical forms for their manifestation. Long, loose hair functions as threads of life, alluding to Aphrodisian vitality and Samsonian strength, while on the other hand, it is the haircloth worn during mourning and penitence. Many different symbols of hair are traceable in our work.

In 1992, the photograph, Madonna with Child, opened an extensive series with linear drawings made of hair braids. It was reminiscent of the enchantment of creation by its own means, with hair braids. This anthropomorphic material expressed an idea of projection out of self, as a transpersonal wave of a personal impulse. It would be better to describe it with the help of mythological devices. For example, in the Vedas, ancient Indian scriptures, creation was linked to the spider and its web. The spider brings a web out of itself like Brahma, dwells on it like Vishnu, and absorbs it back within, like Shiva. This triple process is similar to the process of breathing: inhaling, holding the breath, and exhaling. The creative source acts in the particular moment, in the particular place, thus issuing force, time, and space out of self. In a way, it is a child of itself.

|

|

|

|

|

Pilgrim ¿ 2000 |

Aside of the network

of the linear braids, we use hair as a volume. The filamentous structure

of flaxy hair, in which nature has enclothed woman, serves us as a pseudo

garment and as a haircloth at once. That permits us to create the sublimated

form of the body with the minimum of corporeal density, thus bringing

certain exaltation of the principle of consciousness.

What aspects of the photographic

process do you enjoy the most?

The synthesis of all: idea-execution-result. The processes appear to

be diverse, but at the most fundamental level, they are united and governed

by one central law. The intelligible, the sensible, and the materialized

are not apart; all planes of consciousness and existence are related.

In keeping with the law of correspondence, that which is true and creatively

valuable upon one plane has to be equally true and ingenious upon all

others.

|

||

|

||

|

Grail ¿ 2001 |

Does intuition

and/or an element of surprise ever come into play as you are making

photographs? Or is everything more or less determined and planned

in advance?

Our work is based on intuition, and is full of surprises. There is no controversy

between intuition and a rational approach. Competition and even confusion

can arise if one mixes intuition with instinct. For the untrained eye,

they look alike, but it is not so. Instinct is below the rational, intuition

is above it. Instinct revolts against the conscious orderly approach; meanwhile,

intuition peacefully controls it.

On the practical side, first, we make sketches, then we choose the suitable one from the many; finally, we make a photograph using it as a guideline. The result is usually semi-predicted, since we use Polaroid tests. But our experience shows that nothing is fully predicted. Above all, according to the concept of 'the butterfly effect' the infinitely small changes in the beginning can bring an unforeseen effect at the end.

I've read that you do not use

any digital processes in your image making. Do you feel this an important

distinction for you? Have you considered working digitally in the future?

It just happens like this. We follow certain principles of artistic discipline,

and try to shoot the image as close as possible to our idea, thus avoiding

cropping, retouching, and manipulating the images during the printing

process. For the time being, we make only C-prints. They capture the

subtlety of the skin tones better than computer generated images. On

the other hand, we use Photoshop for design; one day we might use it

for the creative purpose as well. Nowadays, the world is digital, and

there is no sense to object to it.

|

|

|

|

|

Translucent Book ¿ 2001 |

Tell me about

your more recent series, Perhappiness. How did it evolve from

Photoglyphs, and how would you describe your concept of this series?

Indeed, one series grew out of the other. Technically, they differ in the

format: Photoglyphs are mainly done with the Hasselblad, they

are squares. Everything else has a rectangular form. At a certain point

we switched to the Toyo, large format view camera, which gave us better

possibilities for multiple exposures and other maneuvers.

Photoglyphs 'talk' primarily

with words and drawings; Perhappiness is a visionary development.

It encodes the play of intuition, magical elements, the contemplative

state, the aesthetic quest, and more. The wonderworking principals of

photography permit us to give actual flesh not only to words (as in Photoglyphs)

but also to diverse symbols and mental pictures. If you believe the Buddhist

catechism that all that we are is the result of what we have thought,

you simply see our result in what we have created; and that is particularly

condensed in the series of Perhappiness.

|

|

|

|

| Double Sight ¿ 2002 |  |

How would you

define "perhappiness" then?

We see it as a mode of being when 'perhaps' and 'happiness' is entwined.

The word 'perhaps' is rather tricky. It means uncertainty, but at the same

time, it is a possible truth. In life, reality is always overclouded by

illusion, and yet it might be a trustworthy order of existence that suggests

a faithful participation in it. Each of us has a dosage of happiness, which

can be exemplified as perhappiness. When people experience it, in the form

of satisfaction of their wishes, it quickly produces other wishes that

crave another alluring satisfaction. And here one gets into The Rolling

Stones' trap: 'I can't get no satisfaction.' Many live in the incessant

pursuit of pleasures, and that is like a dog that chases its own tail.

Real happiness is unconditioned; it does

not fade away with the change of a situation. It is a balanced state

when the dualism of happiness and unhappiness disappear. A treasure hard

to find. We just hope that the right form of activity, for each of us,

might become a spiritual exercise leading to some worthy aim.

|

||

|

||

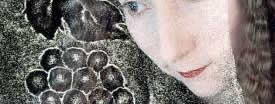

| Fallen Grape ¿ 2001 |  |

The magical part of

this series deals with the play of paradoxes, on which the bittersweet

scenario of life is based. We co-play in it in an absurdist way, trying

to bring a message with the help of a delicate joke, switching to paradoxical

propositions when the rational mind reaches its limit. Art that gives

us the joy of creation speaks a symbolic language of multiple dimensions,

which some of us happen to cross, and others perhaps imagine. Unintentionally,

many of our photographs reflect the weirdness of quantum theories. How

do you like it when an atom can be on the left side and on the right

side at the same time? But if an observer looks at it, the atom 'chooses'

to be seen only in one place. The hypothesis of nonlocality or theory

of the uncertainty principle, sound a little bit like perhappiness.

Nature itself is full of magical tricks. For example, even so-called Paradoxical Frog; which adult is less than a third the size of its tadpole, can serve us as a sample for human society. Why not? Has it not been stressed in different scriptures, that those who wish to become wise must be like children? Of course, it is hard to find among the learned those who would be willing to undertake such a feat. Artists have fewer limitations. We can afford to play with perhappiness.

Looking at your work, I'm curious

to know about the techniques you use--especially in many of the Perhappiness images

where you have transparent objects (veils, books, vessels, etc.). But

then, I think there's something to be said of the mystery of not knowing.

I think I prefer not to know, but I do wonder if you ever tell people

specifics about your techniques, or if they are kept secret?

Conversing with your own thoughts, you already answered this question.

"The mystery of not knowing" sounds fine.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mini Lab ¿ 2003 |

If you weren't

artists, what would each of you be?

The artists again. [sic.] There are changes in appearances and professions,

qualities and quantities, but not in the actual essence.

If you could pinpoint one or

two things, what would you say the great themes

are in your art?

It seems that we are creating sort of an alchemical visual script for

the progressing stages of development that simultaneously touches the

hidden sacral process, and its observable psychological shadow, the higher

and the lower simultaneously. In this context, our Still Performances operate

like living pictures, showing the dynamics not of the body, but of the

mind; like a theater of consciousness, with deviations into supra- and

subconscious content. We compress the meaning into a symbol, which in

reality far exceeds all visual and verbal representations. Each can verify

the reality for himself using his own methods. Our vehicle is art. It

is useful until it leads us to the essence, but as soon as this essence

is realized, there is no need of any vehicle. If understanding already

exists inwardly, then outside of this, there is no right finding. Then,

maybe we shall cease to be artists.

|

|

|

|

|

Compasses ¿ 2005 ( with metal relief) |

What have you

been working on most recently? Do you have any thoughts on what

direction your art might go in the future?

We are working on a new series that is sort of a hybrid between photography

and sculptural metal reliefs. Seeing that our creative experience was poured

into a multiplicity of visual forms, much more than meets the eye, we said

to ourselves, "It's time to verbalize the results of our doing." May we

borrow the line from Walt Whitman, who expressed a similar feeling poetically: "Walt,

you contain enough, why don't you let it out then?"

Now we are writing a book, while continuing

our photographic projects as usual. We feel the necessity for interpreting

what we have done and what we are doing now. No art is safe from the

hermeneutics.

|

||

|

||

| Reading Light ¿ 2002 |  |

What does your art mean to your life, and to your life together as a couple?

We used our art to map the inner space, and at the same time, to coax allegories of life from beneath the surface of physical reality. At this point, it would be better to revert to our explanatory text that we were asked to write for our recent exhibitions. It is about a gradual unfolding: some quality is emphasized in the first watch, then another essence is uncovered in the middle watch, and in the last one, at sunrise everything can be unified.

|

|

|

|

|

At Glance ¿ 2005 |

In

the pursuit of 'perhappiness' in life, we tend

to

follow our feelings, not the instinct;

to

follow our mind, not the feelings;

to

follow our intuition, not the mind.

Amid all kinds of wonders, it is a process of finding the articulation

for the soul.

The

upcoming events: participation in the exhibition Russia! at The Guggenheim

Museum Sept. 16 - Jan. 12, 2006 and in Private Pictures: Photography

from Arizona collections at The Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art,

Sept. 24-Jan. 8. Solo exhibition at Lisa Sette Gallery, Scottsdale, Az,

Feb. 2 - 25, 2006.