Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin

pHOTORELIEFS

© 2010, Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin

part 4: SQUARING THE circles

There is an ancient dilemma behind the idea of the squaring of the circle; that geometric operation has baffled many mathematicians and even more theologians (who viewed the soul as a circle that occupies the square of the body). The square not only implies the basic arrangement of the world but mans’ constructive attempt to achieve permanence in material life. Yet, amid the flux of nature, only change itself is unchanging. Nature’s permanence is akin to a limitless circle that can be traced in an orderly repetitive motion: from the orbs of the planets to a single drop of rain.

Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Bath of Hera © 1995, C-prints in aluminum construction with pencil drawing |

The circle is the simplest diagram of the self-enclosing and self-sufficient matrix of life. Demonstrating the cause of sameness to all things, that dynamic pattern underlies every system in nature, from celestial orders to the constitution of the atom. In that sense, the universe is just a part of a larger “multiverse.” In medieval thought, God is a circle whose center is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere. It might be paraphrased as follows: the center of all is in infinity that does not have a center. In ancient sacred architecture and in every scheme of cosmological geometry, the square and the circle are brought together and made commensurate. The same meaning is concealed in the complex oriental mandala.

Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Squaring the Circle © 2006, C-print in aluminum construction |

Since all things share human nature, that geometrical operation frequently assumed an anthropomorphic form in our artwork. Naturally, all these ideas have their projection not only in the art but also in real life. Relatively speaking, some of us are trying to circle the square, while some are squaring the circle of others. Employing two geometrical figures – the circled square and the squared circle – symbolically we touched upon the a priori contradiction: immaterial perfection vs. material imperfection.

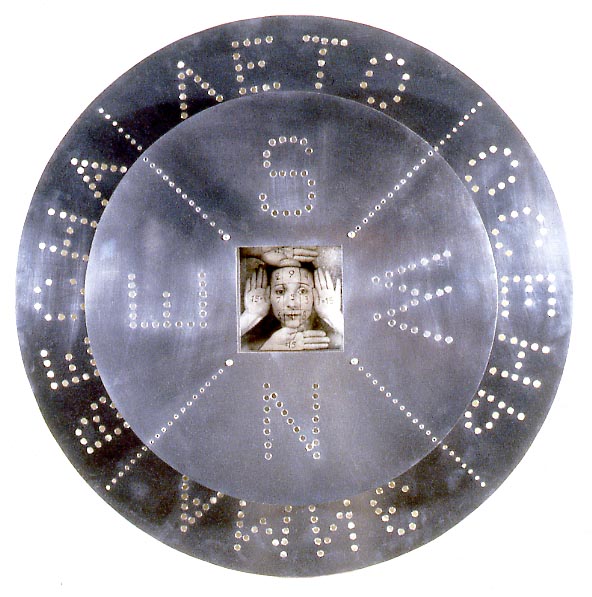

Valeriy Gerlovin, Round Magic Square © 1987, 24" in diameter, 3 ½" deep, aluminim, b/w photo |

Many Valeriy’s metal relieves depict the square and the circle, Round Magic Square, par excellence, alluding not only to the mandala but also to the already mentioned dilemma of squaring the circle. In symbolic logic it is one of the ways to merge the infinite with its finite expression, while literally, it is a construction of a square whose area is exactly equal to the area of a given circle. Aside of its mathematical property, in many esoteric systems that classical problem is considered to be a metaphorical expression for possible regeneration – it contains and reconciles all oppositions, including time and space, universal and individual, spiritual and physical, sacred and profane, heaven and earth, or the circle and the square. That is one of the geometrical patterns associated with the quinta essentia, the vista towards returning to the condition in which soul and body are not different.

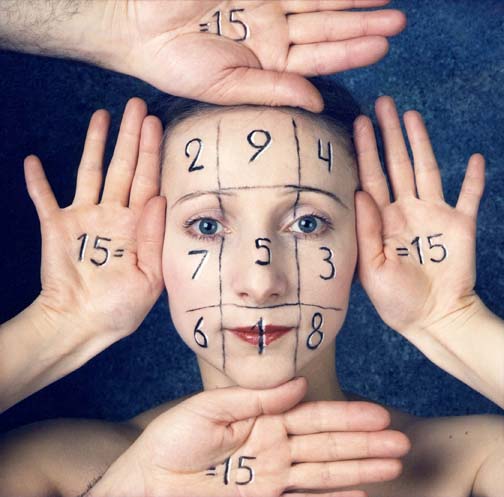

Gerlovina, Berghash, Gerlovin, Magic Square © 1987, C-print, collection of The Art Institute of Chicago (link) |

The symbols, after all, are not the property of one culture or a certain period; they dominate all mankind. The same can be said about art, especially if it is employed to demonstrate theoretical ideas. Incidentally, the very meaning of the word “theory” in the original Greek pertains to both “viewing” and “contemplating,” thus uniting the visual and the rational, suggesting a method of “thinking with aesthetic guesses.” Therefore, it was quite natural for both of us to convert or rather rethink the important concepts of our sculptural works into anthropomorphic images. Even more so, we integrated both circuits by uniting objects with photography, as in this series Photoreliefs. Round Magic Square – encompassing the four cardinal points and the four seasons – was literally “physiognomized,” the face added somewhat mystifying deepness to its polished symmetry; for the face is the psychological center of this work, a focus that emblematically enlivens the object and its static features.

Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Section © 2006, C-print in aluminum construction, engarving |

All our works are based on geometrical principals imbibed with symbolic logic, functioning on the intersection of art and spiritual properties. There is no need to further categorize the Photoreliefs made in a variety of forms, other than to mention that the Superstrings (a motif also treated in Perhappiness) depicts the correlation of actual strings with their photographed “doppelgangers,” as seen, for example, in String Pyramid.

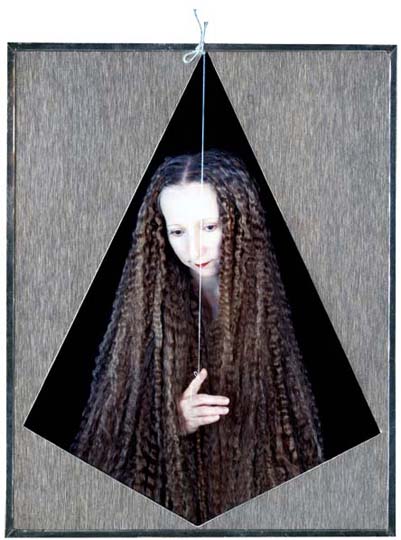

Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, String Pyramid © 2005-10, C-print in aluminum construction, stainless steel strings |

All long vertical threads are real, while their wrapped-around-the-finger extensions belong to the flat land of photography. Making the pyramid by threading through its “dark valley,” we enter the field of projective geometry. One of its axioms is that parallel lines meet at infinity, so we tried to envision in our metaphoric pyramid. What if its strings are also parallel while we see their projected meeting at the infinity of the pyramid’s tip? One picture is worth ten thousand words,” says the Chinese proverb, so we leave the picture to talk for itself.

Man’s eyesight easily creates an illusion: we see that the sky and the earth meet on the horizon that departs from us proportionally to our nearing to the deceiving point. Not only the eyesight but also the field of vision of the intellect can be deceptive, both in the bad and good sense. The mystics dared to take flight along the vertical line crossing the mental membrane of the rational horizon. The level of intelligence of each person determines the limit of rising.

Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Thread Pyramid © 2006, C-print in aluminum construction, thread |

There is no pyramid per se, and yet it is there. The thread is a photographic image literally at the fingertip, while its knot on the top of the virtual pyramid is real. No need to extend the line into the bottom of the pyramid – the “framed” imagination works by itself. The borders between the various layers of reality are obliterated, just as there is no ultimate division between the white light and its spectral diffusion. Indeed, perhaps, there’s no stringent separation of mind and matter – which is the underlying meaning of the series Superstrings.

Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Rays © 2006-10, C-print, aluminum details, threads |

The same paradox can be articulated in different ways. The work Scales resolves the conflict of the irrationality through the balancing of the composition, maintaining parallelism between the scale and the top bar of the frame. Sometimes the mind’s eye might be (delightfully) confused by the perceptual inversion and “asymmetric” symmetry.

Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Scales © 2008, C-print in aluminum construction, engarving |

In Scales, the flat frame is an impossible four-bar that the human eye accepts as a solid. There are a number of impossible figures that cannot be made in 3-D reality, yet can be drawn, imagined, or, perhaps, brought to life in virtual worlds. If we move along in a 4-D direction, the ungrasped and ungraspable would lose their mystery. It seems reasonable to suggest that what is physical in 4-D context is metaphysical in 3-D reality, and what is physical there, would be metaphysical in 2-D context. On the other hand, if all is one, division into physical and spiritual aspects is relative; therefore many of our works seem to belong to their borderland.

Framed this way, the “flat relief” Scales depicts what is rooted in the old iconography, namely, the judgment of the egg. It is put on the scales of an ethereal kind: no dishes, no weights, just a stick on the thread. The egg is balancing on the stick as a ropedancer, whose life is hanging on the thread. Why that? We hope it would not offend common sense if we suggest that the egg is a euphemism for ovum humanum (human egg cell). Metaphorically speaking, man’s psychological “embryo,” his innately sensitive, fragile part of a personality, seems to be ever hanging on a thread of mental arguments and judgments, like that balancing egg. The equilibrium of the egg depends on the correct tip of the scale; one ought to be proportioned to the other. That requires certain mental balance and, perhaps, spiritual equilibrium in any event, including the impossible four-bar situation.

Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Echo © 1995-06, C-print rimmed with the aluminum strip |

Choosing the simplest ideas we use them with the oddest twists, revitalizing them by the spectator’s interest in their picturesqueness. Remodeling the echo phenomenon by reversing its audio effect visually, the image Echo alludes to the Greek myth of a mountain nymph who was able only to repeat the last words of anyone spoken to her.

Many of our concepts are inconsistent with common sense, but consistent with deeper understanding. We try to convey messages through subtle humor, switching to paradoxical propositions when the rational mind reaches its limit. Nature itself is full of magical tricks. For example, in the case of the so-called paradoxical frog, the adult is less than one third the size of its tadpole and can serve as a model for human society. Why not? Hasn’t it been stressed in different scriptures that those who wish to become wise must be like children? Of course, it’s difficult to find among the learned those who would be willing to undertake such a feat.

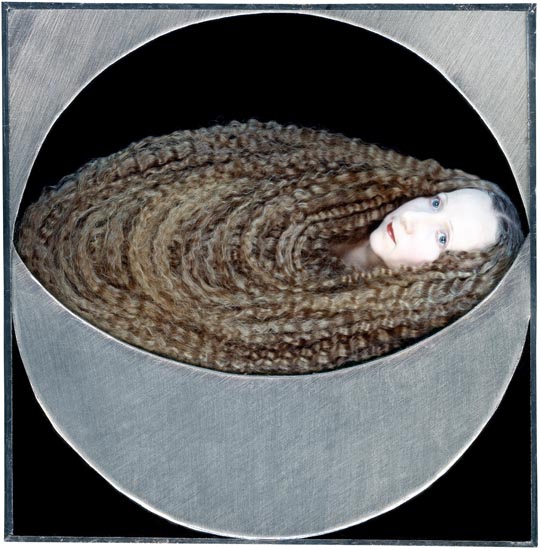

Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Pupa © 1992, C-print in stainless steel frame in the form of mandorla, 60 x 36" |

Suggesting a potential series of reversal and counter-reversals, we do not want to dramatize the matters but simply say that the true understanding comes through numerous approximations to revelations received in a state of reverence. In simple words, the truth is usually accepted with the spontaneity of a child’s reaction. In spiritual birth, the regeneration or passing through the opening in the matrix of nature, symbolized by the almond-shaped mandorla, an aureole in shape of a vesica piscis or a cross-section of two circles. In the medieval art and in the Russian icons, Christ is often shown within the mandorla indicating the sacred transcendent moment, such as transfiguration, resurrection, and ascension.

Many of those age-old experiments which in truth are a singular flow continually “trespassing” the property of matter – were associated with spiritual and religious quests, ascetic practices, hermetic procedures, or alchemical opuses. The latter, in particular, are not far from artistic creativity, judging by alchemists’ mad inventiveness, obsessive aspirations, and, most of all, visualization – a technique of producing images expressing ideas.

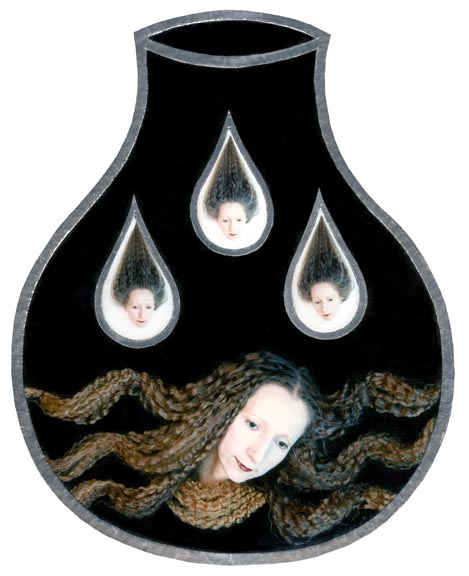

Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Fire Flask © 1996, C-prints in aluminum construction |

Alchemists utilized an arcane symbolism not only from the scriptures and mythology but also from works of art and literature. Even though the results were sometimes as substantial as clouds penciled against the sky, some effects corresponded to their creative aim or at least their half-contented curiosity bringing a wave of fresh enthusiasm. With the imagination abstracted in realms of sanguine expectations, they produced an unusual visual vocabulary and coined certain useful terms in a somewhat collective way. They viewed the transformative process through the alchemical prism that separates the entire process into stages as if separating the light into the colors: nigredo, albedo, citrinitas, and rubedo.

Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Water Flask © 1996, C-prints in aluminum construction |

Suggesting all kinds of hypotheses mixed with all kinds of facts that make the mind exercise by imagination, we seemed to create an alchemical visual script, depicting the progressive stages of development of the psyche in the objective sense. Replete with the weird and wonderful chain of references between art and life, the works touch on both the hidden sacral process and everyday reality. Born from the inner vision, these images helped us apprehend the archetypal ideas that entered our minds as people enter their houses. We experienced them as alive in our consciousness. The concepts are not only openly exposed on our own faces, thus bearing the seal of direct experience, but the systematic, diary-like approach added stone upon stone to the pile.

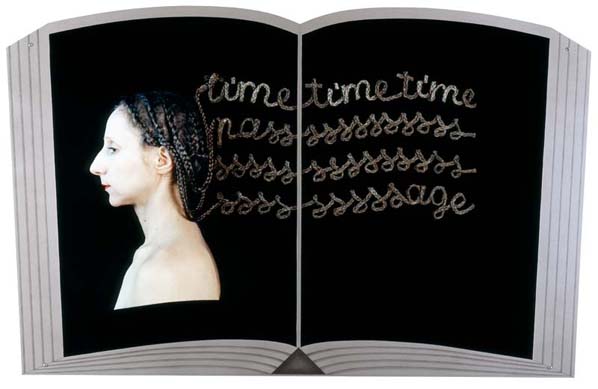

Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Book (Time Passage) © 1994-5, C-print in metal relief with pencil drawing, 26 x 41" |

“I am“ is weaved into the t-i’m-e passsssssage. Man is a prisoner of time; upon opening its book, he is reluctant to close it. The heart of the matter is that time is a finite measure of the infinite. From the point of view of eternity, all changes in time are relative, while for a man, who is limited by time and his own linear thinking, they seem to be absolute and irrevocable. Both time and life do not permit man to come back or get ahead of his own destiny, leaving out only a possibility of mental regressions and progressions. Retreating mentally from time and its linear traps, one begins getting glimpses of freedom, because there is not just one time, our time, but an infinity of times, mirroring each other.

Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Live on Time © 1993, C-print in aluminum construction with mirror |

The mirror forms changes, while the subject behind it endures. A mirror of itself suggests self-examination. In Live on Time, a sculptural diptych combining a photograph and a mirror, the subject of time is interpreted somewhat reciprocally: inscribed on the forehead, “live on time” reads as “emit no evil” in the looking glass. That “backward” meaning brings another value in living on time that can go on and on in its vegetative dormant aspect if or until something of another merit does not interfere. The idea behind the mirror image is too obvious to discuss it at length. In simple terms, do not do things to others, which you do not want to be done to you. Everybody knows it, and yet so many people follow a different motto – an eye for an eye. The living principle of mutual causality is both supportive and disruptive. Like a mirror image of the image, that “tenet” is a self-evident palindrome.

![]()

Giving voice to the great authorities, we shall also express our thoughts upon that delicate subject. “The Good must be the Good not by any act, not even by virtue or its intellection, but by its very rest within itself,” said Plotinus.13 The goodness shows itself in a sacred duty that does not expect favors in return. Must we forget that any discussion of righteousness is veiled by people’s understanding of it, since every man looks good and innocent in his own eyes? And such eyes deserve in some great measure to be mistrusted. Dante left us the timeless formulas on that account: ”The flesh of mortals is so soft that on earth a good beginning does not last from the springing of the oak to the bearing of the acorn.” To counterbalance the “load,” he envisaged also in Paradise: “A soul in bliss cannot lie, since it is always near the truth” (Canto XXII and IV). In the cool observation of Shakespeare: “There is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so” (Hamlet, II, ii, 249), while for Pythagoras, as much as it is known about him, to search for good from any but the divine source is foolish. Naturally, for us it would be easier to use a picture language: all our thoughts happened to be processed through our art, which allowed us many liberties.

Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Chest © 1995, C-print in aluminum construction |

As artists, we have no confidence in the uninspired reason; therefore our hermeneutic follows the images. In general terms, in order for someone to see the true nature of good or evil, this person must be beyond good and evil. Only those who have inner clarity of mind wedded with simplicity of heart can discriminate properly the superior from the inferior. Nature is neutral; that is why if the intentions are evil, nature will nurse them just as if they were good and righteous. Often evil was interpreted as an absence of good. It might be so, yet that malefic “absence” makes its presence felt in the world. Demonstrating power of its own, it seems to operate rather rationally through various sources and forms, natural phenomena, or human organisms of a wicked disposition. Nature produces nothing unmixed on earth; every light has its shadow in the underlying principle of genesis.

Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Between the Fingers © 1995, C-print in aluminum construction, pencil drawing |

The ethical way of living in time and emitting no evil is far from being an isolated personal experience bathing in the virginal substances of the soul. It is a life in a conditional situation among other kinds of anthropos and hordes of anthropoids; it is filled with prolonged days and years of many undesirable events. To go through the friction of the great and the small requires certain patience and resilience. The clever Latin proverb, also a palindrome, expresses the same idea with a unique accuracy:

Subi dura a rudibus

“Endure rough treatment from uncultured brutes” – reads from both sides. Endurance is a spiritual castle, fortified from all sides against the hostile attacks of whatever kind. The world is an objectification of our consciousness; therefore the inward conquest often has its crown in the outward mastery of the circumstances. The other way around is more perplexing since the outward mastery without inner security of ethics easily degenerates into indulgence in power. In a time of an erosion of ethical values, it is especially difficult to maintain the integrity and emit no evil. One also has to rely upon a symbiotic and mutually supportive feedback in spite of nature’s predatory ecology. Does that not mark off mankind from the beasts? The possibility of resisting evil is hidden in the raising of oneself to another level of consciousness.

Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Opening Eyes © 1991, C-print in aluminum construction, pencil drawing |

The forces that are benign are more powerful than the destroying forces. That is a great consolation built right into the scheme of things. Otherwise, life would never exist, being destroyed before even coming into existence. In time of tribulation being “good” is necessary for the sake of one’s own survival. In that aspect, man’s own immanent consciousness (or his soul, if you prefer,) is the most severe subconscious judge of his doing, of his “emitting,” reflected in the faithful mirror of time. “God will pardon me – it’s His profession,” as Heinrich Heine said on his deathbed.14

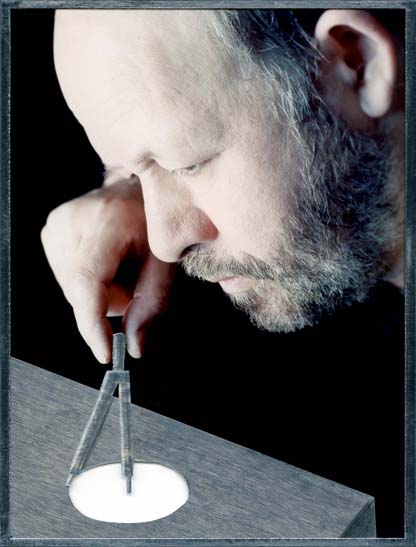

Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Compass © 2005, C-print in aluminum construction |

Some people understand and observe themselves only in a constant state of flux, while artists do so through their art. For example, the paintings of Goya or Dalí enable us to easily trace their psycho-mental trajectory. It seems that if that trajectory is to reflect a unified consciousness, it crystallizes in a tripartite progression: in the beginning, one gives priority to feelings over instinct, then to mind over feelings, and, ultimately, to higher intuition over mind. Revealed in the sum of every natural and human event, intuition is qualitatively different from instinct. To the untrained eye, they appear similar, but that’s not the case. Instinct is below the rational; intuition is above it. Instinct revolts against the conscious, orderly approach; meanwhile, intuition peacefully controls it.

The overall picture of our photography weaved in this essay shows the similarity of ideas underlying a diverse array of artworks, which differ in media and time of creation, but carry the same fully consistent message. But there’s more. With spiritual aspiration serving as the chief focus of our lives, we’ve been engaged in a “life search,” knowing that our own destinies could come to fruition only through our art. Perhaps the following is an accurate enough analogy for our photographic practice: similar to the work of the chemist, who employs tinctures and flasks for his experiments, we’ve used our minds as solutions and our faces as vessels, thereby extending the roles of observers and observed to the unifying state of being the observatory itself. It’s like having an intention, and not having one. In technical terms, this method was convenient, compact, and self-sufficient.

Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Aperture © 2006, C-print in aluminum construction |

From the artistic point of view, for us it wouldn’t suffice to reproduce an experiment on the face if something behind it did not transcend and give a sense of mystery. The mental ability to grasp the nature of being is tested within the context of world events, the consequences of which are imprinted on the human psyche. First comes the reception of knowledge (visual or verbal), then its absorption, and, finally, its application. It’s a gradual development of the inner capacity for metaphoric truth, apprehended when one wants to apprehend the creative order of things. We hope that via the artwork, the sacred can enter the everyday world and somehow influence the viewer. Perhaps this psychological dramatization and its analytical synopsis can somehow inspire others as well. Each can verify the reality for himself using his own methods. Our vehicle is art. It’s useful until it leads us to the essence, but as soon as this essence is reached, there’s no further need for any vehicle. If understanding already exists inwardly, then outside of this, there’s no right discovery.

FOOTNOTES:

1. St. John Cassian, The Philokalia, collection of the Christian Orthodox writings dated from the fourth century and later, translated by G.E.H. Palmer (London, UK: Faber and Faber, 1983), vol.1, p.77.

2. Arthur Schopenhauer,The World as Will and Representation, trans. E.F.J Payne, (New York; Dover, 1969), vol. 1, p. 404.

3. William Shakespeare, The Tempest, Act 4, scene 1, 148-158.

4. Reference to the painting The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch.

5. C.G.Jung, Mysterium Coniunctionis, Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Vol.14 (Princeton University Press, 1977), p. 162.

6. Franz Hartman The Life and Doctrines of Jacob Boehme (Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., London, 1891), p. 326.

7. Heinrich Zimmer, quoted by Joseph Campbell in The Hero’s Journey, (Harper & Row, San Francisco, 1990), p. 41.

8. Aristotle Metaphysics XII:9, 1074b.

7.

9. Adi Shankara, Garland of Questions and Answers (Prasna-Uttara-Malika))

10. Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy, section 14.

11. Gospel of Philip 84:30.

12. “For the spirit of the living creature was in the wheels.”(Ezekiel 1:20).

13. Brihadaranyaka Upanishad (11, 4, 15).

14. Plotinus, The Enneads, translated By Stephan MacKenna (Burdett, New York: Larson Publications, 1992), Chapter I, p. 74.

15. “Gott wird mir verzeihen, das ist sein Beruf,” Heinrich Heine in Letzte Worte auf dem Totenbett. Quoted in French in The Joke and Its Relation to the Unconscious (1905) by Sigmund Freud, as translated by Joyce Crick (2003).