< home < content next: part 2 >

RIMMA GERLOVINA AND VALERIY GERLOVIN

PHOTOGLYPHS

© 2010, Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin

PART 1

In our work in photography, we tend to explore what's given indirectly by means of direct examples, shifting the spotlight from conceptual object to conceptual subject. A meditative approach adds to the unhurried quality of our visual story, which, in reality, is the story of the self-fertilizing processing of our art into our life, and vice versa. The knowledge embedded in the form of immediate experience is endlessly revealing. In our creative practice, a vast array of ideas is seamlessly interwoven with consistent means of expression, the most dramatic of which is the use of the human face as both witness of performance and canvas for its representation.

"In the beginning was the word." So it was in our case, too. Words as symbols of thoughts can be taken as visual units, which leave room for multiple interpretations. True to its title, the series Photoglyphs, which literally means "carving with light" (in Greek phos, photos - denotes "light," and glyphe - means "carving"), mainly features close-ups, with cryptographic words and drawings. We photographed the "chosen" words, inscribed on our faces between the eyes and brows, and on the forehead and neck, without verbal context. Skin was utilized as human parchment for the visual formulas. Deploying this curious organic metaphysics not within the "bookish" environment where it's usually encountered, but directly on our faces, we tried to transfer it to the realm of poetic truth. In this new context, words, developed from the flesh and blood of visual poetry, appeared in the fullness of their allusive meaning, not as faceless morphemes of a linear textual form. Presented right on our faces, the front pages of the mind, our thoughts thus became visible, recharged by our own features and expressions. Almost like visions that appear to the inner eye of the imagination, these manifested thoughts enabled us to articulate perennial ideas as we experienced them in ourselves.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Aqua Vitae © 1989, C-print |

Visual poetry involves not only wordplay, but also the choreography of verbal images. For example, the fluid, shapeless water in Aqua Vitae assumes the form of rolling waves with words tossing on them. Vita has its beginnings in aqua; therefore, the word-for-word expression "aqua vitae" (water of life) faithfully reflects the origin of all formations. The vibrating lines depict the bottom of the procreative primary waters, from which emerge the fingers with the red inscription "vita." The firmament is rising with the open eyes, and the forehead is turned into a field for the piercing action of the two horn-like "A's," the first letter of many alphabets, the alpha of the beginning. Water mediates eternity with impermanence - aqua is always vita. No experience in the waters of life can be exactly repeated; no destiny can copy another. Like a wave, each individual life appears and then submerges into that water; speaking proverbially, all waves belong to the ocean, while the ocean does not belong to waves.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin,Time - Emit © 1989, C-print |

The mirror conundrum Time - Emit deploys a similar motif. "Emit" is written on the forehead, suggesting the seat of mental emission, while "time," which appears in reverse, is inscribed on the glass surface, glistening with water droplets. In this way, "emit" flows into the upside-down "time," much like the fading, and subsequent merging, of energy into matter. It's as if we unintentionally visualized the theory of relativity, depicting its link of emitting energy, mass, and time. After all, is man not swimming in their tridimensional realm, like a fish in water? A fish is unaware of water; it just lives in its "here and now." The aqua vitae remains an eternal puzzle: "nobody can enter it twice," posited Heraclitus. Moreover, added Paracelsus, "A fish taken out of water does not leave a hole in it." In the same vein, another "truism" has coined itself in our imagination - water cannot be drowned.

| Rimma Gerlovina, Mark Berghash, Valeriy Gerlovin, Fish: "Reality laziness Echrista is preordained" reads with different intervals as "appearance of Jesus before people" © 1987, C-print |

Fish, one of our rare works in the Russian language, also manifests a relationship to water, but in its purifying sense. Infusing words with another impulse, we tried to make a picture of thoughts, which in and of itself might be a plentiful source for both knowledge and the imagination. Besides, visual language can conceal more than it reveals. Reduced to its hidden meaning, it might be impregnated with deeper significance, so that the Word can be heard behind the chorus of words. Certain mystical ideas require no interpretation; they seed themselves into man's consciousness if it's subtle and receptive enough. Such ideas might herald a certain type of knowledge, which might be more akin to faith. On that score, it's useful here to recall Albert Einstein's famous saying, "The finest emotion of which we are capable is the mystic emotion... and anyone who is a stranger to it is as good as dead."(1)

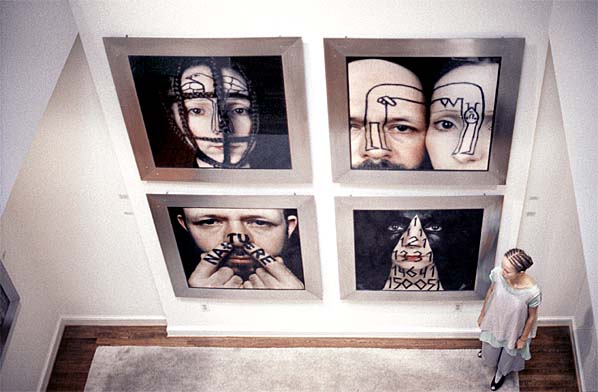

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, installation view of the joint retrospective exhibition An Organic Union at Fine Arts Museum of Long Island, Hempstead, NY, 1991. (Left) metal sculptures by Valeriy Gerlovin, (right) joint work Photoglyps. |

The Photoglyphs were made at the crossroads of various genres, summarizing certain tendencies in our art that closely relate to the whole sequence of "perhappenings" in our lives. Since we've always created our own conceptual objects, our collaborative work reflects each of our practices and concerns: the close-up technique and the metal reliefs derived from Valeriy's murals and metal sculptures, whereas the visual poetry came from Rimma's cubes and circles. The residue of all of our previous creative efforts, their essence and significance, was now displayed to us through the magnifying eye of photography. Thus, renewed by this new approach (with the help of the camera), diverse photographic concepts gushed forth like an allegorical fountain of ideas. Consequently, we became less and less interested in making objects and in performing. Our performances now became "still."

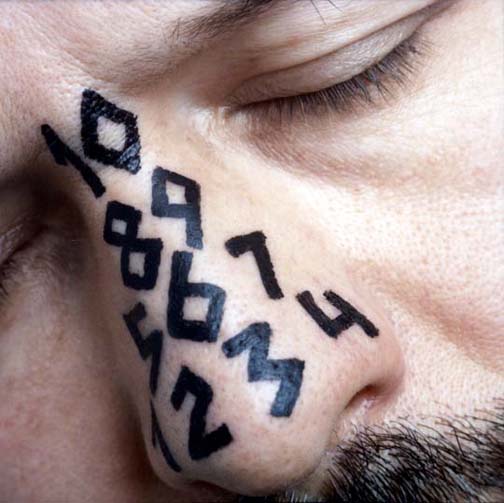

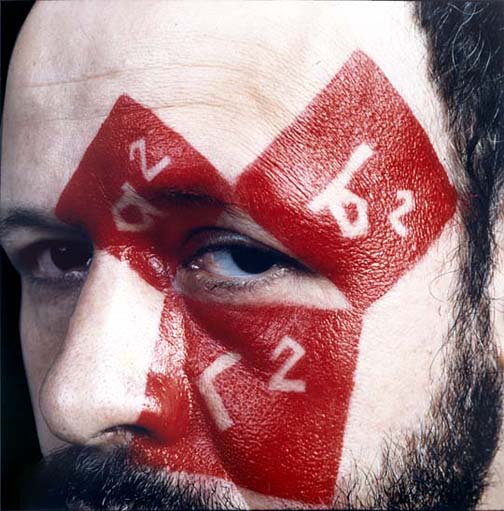

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Calendar © 1989, C-print |

Compressing meaning into a symbol, we wanted to look not at the object, but through and beyond it. With time, our separately developed pictorial concepts grew into elaborate collaborative series, the connections among which were as decisive as they were inexplicable, although the key principle behind them remained the same - how to make the world from oneself, rather than oneself being made by the world. Observing our own conditions and at the same time conditioning them, we were putting everything on the visual record, thereby creating an unbroken chain of several hundred images. Saturated with complex metaphorical meanings, the words and numbers in our "still performances" operate like tableaux vivants, showing not the dynamics of the body, but the mind, like a theater of consciousness with deviations into supra- and subconscious content.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Sphinx © 1990, C-print |

Although the camera is a dubious instrument for visualizing esoteric concepts given its immense popularity, nevertheless, it was well-suited to conveying our ideas. We saw how the initial physical content of a photograph, which simply reflects its surroundings, can be extended to a hyper-physical content and infused with multi-leveled symbolism. From antiquity comes the Ovidian maxim, "True art conceals the means by which it is achieved." In other words, art must appear artless; the goal is to express oneself in the common language of the people, but to think like a wise man. This language not only entered our work via the camera, it was also defined by our choice of a traditional subject: the face. However, the visual plasticity of art and its underlying concepts enabled us to give voice to something more than that common language, magnifying the magical emanation of such realities that can hardly be expressed by words.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Tetraktys © 1989, C-print |

For the series Photoglyphs we used Pentacon and Hasselblad medium-format cameras, 2¼ x 2¼ inch- (6 x 6 cm), later switching to a Toyo, 4 x 5 inch- (10.2 x 12.7 cm) view camera, which afforded us enhanced possibilities for multiple exposures and other photographic maneuvers in the next series Perhappiness. By shooting the image as close to the original concept as possible we were able to minimize the need for cropping, retouching, and manipulation during the printing process. The photographs were based on sketches, but at the same time, they were created on the spur of the moment. In fact, looking back, we understand that all our lifelong efforts in art in general and photography in particular were rather spontaneous and, to a certain degree, effortless.

| Rimma Gerovina and Valeriy Gerlovin Installation views at Robert Brown Gallery, Washington, D.C.,1990 |

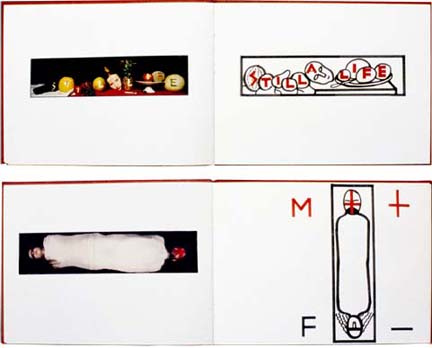

Printed with extreme sharpness of detail without any computer alterations, the color photographs were displayed in artists' metal frames (48 x 48 or 36 x 36 inches) or sculptural metal constructions of different sizes. Many of the albums with preparatory drawings resemble collections of visual poetry. Selecting the most suitable of the drawings to shoot, we photographed two concepts per session, usually twice a week.

| Rimma Gerlovina, pages from the album with the drawings for photographs ©1988, 100 pp., 9½ x 12½ x ¾". Link: The Sackner Archive of Visual and Concrete Poetry featuring another album Kniga-Book. |

| Rimma Gerlovina, Mark Berghash, Valeriy Gerlovin, view of exhibition Two for Tango, The International Center of Photography, New York, 1988 |

If one is capable of noticing things hidden behind other things, as well as their mutual interchange, all phenomena begin to appear as part of a single multiplex. The flat land of one meaning is absorbed into this fullness. For example, the composition Real (1989) is photographed literally under the veil of reality: the word "real" is shown not in the usual linear manner, but as a three-dimensional configuration. With its seemingly loose ends, the living principle is never static; it's pacing like the human mind, which is perpetually in the motion of thought.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Real © 1989, C-print |

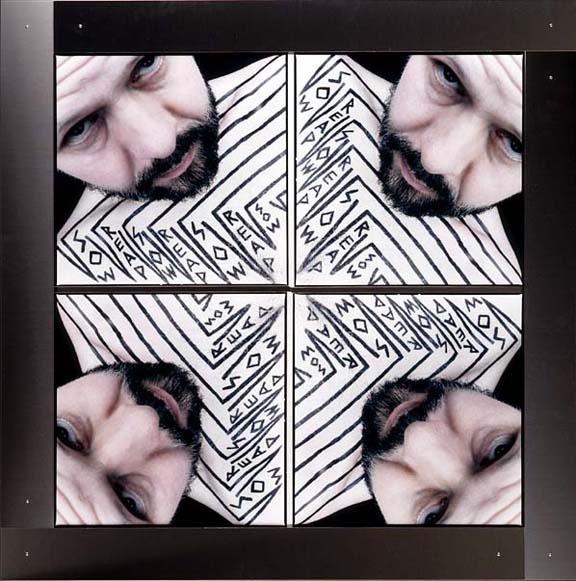

Expressing that concept on the face, we joined the abstract idea with its mental equivalent, giving "evidence" of its physical presence. Reality is thus seen behind the veil - a veil that's often of our own creation, perhaps made of hair, or perhaps of thoughts. In any case, for the average person "reality" remains a hazy concept, a gross material dream that turns the wheel of the world. It's only when we awaken from a dream that we know that we've been dreaming. It might take many circles of pacing in this virtual reality before the thought of waking even starts to make its way through the twilight activity of the mind. Nature seems to circulate everything with spontaneity within its immanent paradigm of life and death: while sowing, it is already reaping. That very process is depicted in the "quadraphonic" composition of Sow - Reap (1991), in which language is used ontologically.

| Rimma Gerovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Saw - Reap © 1991, C-prints in stainless steel construction, 48 x 48". Collection of Progressive Corporation, OH, USA |

In the kaleidoscopic wheel, the square roots of the words "sow" and "reap" shoot their fractals into all directions. In a chain reaction, every square root is taken from another - just as, in the tree of life, each life changes the course of another. The visual plasticity of photography permits not only the encoding of archetypal ideas, but also the creation of an aura filled with the powerful emanation of human presence. Sow - Reap depicts the functions that the Hellenes attributed to the god Kronos or Father Time, the grim reaper that ruled their galactic graveyard. It made no difference to him whether it was a grave of cosmic proportions or a lot of a single individual. Even if everything is destroyed by time, time itself is still not destroyed.

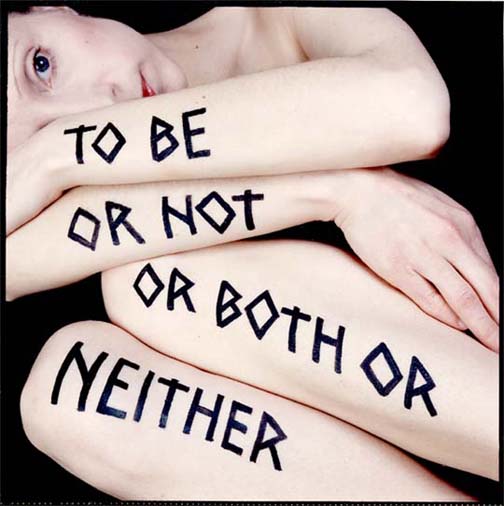

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, To Be © 1989, C-print |

In a similar manner, the photograph To Be (1989) sets this literally bare figure of speech upon a speculative background. Hamlet's dilemma is updated here to our time of relativity, while the added "footnotes" ("or both or neither") generate a koan-like ambiguity. Perhaps Hamlet's morbid thoughts and "heroic" deeds are such, because his consciousness is judged by his ego, whereas it's supposed to be the reverse. The ego wants to live, but if it doesn't live according to its expectations, it's ready to die and drug alongside all others. The ego isn't connected to immortality, but simultaneously desires and hates it. The body dies, and its reason dies along with it, unless consciousness is not colonized by the body-ego complex, with its shallow mode of thought. Yet, this is only one side of the famous question. The finite mind is continually engaged in a struggle with the concept of the infinite. Meanwhile, from the perspective of infinity (and therefore eternity), Hamlet's question is irrelevant, since there's no basis for such an enquiry. Perhaps, it's not so much a matter of ceasing existence, but merely of seeing it in a wider aspect. Death is part of life, much like night and day are part of the twenty-four-hour cycle.

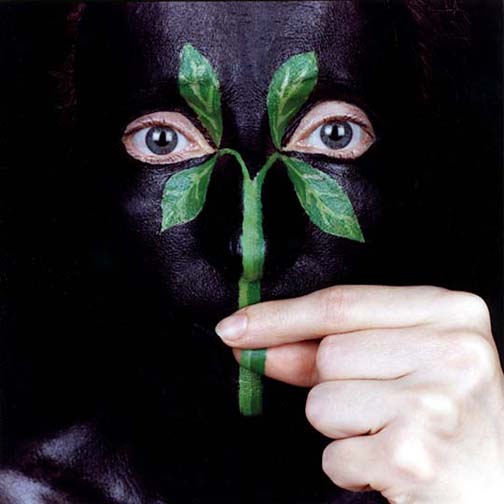

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Looking Grass © 1991, C-print |

The marriage of the two foremost contradictions ad absurdum can be expressed through a paradox that contains a solution for being and not being in simulcast. If we accept that there are different dimensions in one locality, then both being and non-being in one particular reality could simultaneously mean existing in some other, upgraded reality in which being and non-being can coexist. Locked into a struggle of opposites, our polarized mind can barely grasp the dichotomy. Such requires an elevation of consciousness beyond the dualities. To avoid needless argument, we suggest that the final stage of "neither" is veiled. It includes all previous experiences and converts them into something radically new in which all qualities cease to exist. Pondering the rate of mortality, one can arrive at a counterclaim: what, then, is the rate of immortality? And where to seek it: in the body, out of it, or both or neither? Who can jump out of one's own body safely, and if so, into what? One thing is certain - the answer lies beyond the trapping duality presented in binaries of matter and spirit, being and non-being, male and female, and the like. If so, perhaps we are immortal mortals as much as we are mortal immortals.

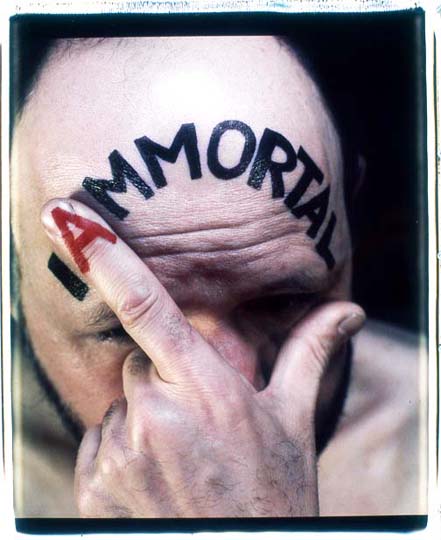

| Rimma Gerlovina, Mark Berghash, Valeriy Gerlovin, I'mmortal ©1988, Polaroid, 24 x 20" |

If we superimpose these two modes of existence one onto the other, we can obtain an everlasting extract from their conjunction that we tried to encode in the photograph I'mmortal (1988). That's precisely the instance when "to be or not" becomes the coexistence of "both or neither" in one locale. If led to the level of immediacy (as in certain hesychastic practices or yoga), the finite mind may glimpse the dissolution of all bonds into nothing.

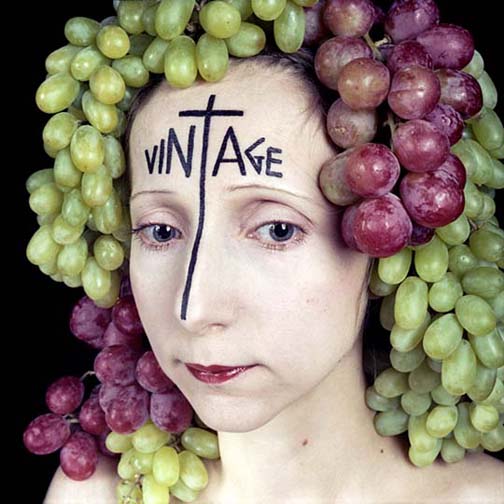

Visual poetry inscribed on the face permits not only the distillation of metaphor, but also the intertwining of factual and poetic, physical and metaphysical. Vintage (1990) seems to be an example of such blending.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Vintage © 1990, C-print |

By its very nature, life is not at peace; in a symbolic way it rests on contradictions, our share of which increases once we begin to recognize them. Not for nothing do we have our vintage of pain and pleasure, which chase and cancel each other out. For that reason, this image of harvest bears the stem of a cross that casts a shadow of doubt on the fruitful adornments of the head. Grapes are our food, our wine, and they can be sour. The words "vine" and "age" seemingly wrap around the cross, hinting at Dionysian mysteries through a well-developed symbolism of wine, uninhibited lifestyle, and above all the allegories of death and resurrection. Grapes of plenty are mixed with "the grapes of wrath." As any knowledge tends to be put into action, the meaning of this work is not confined to wordplay. The world doesn't only consist of ideas; it's also alive, like a vineyard in grape season, in which the harvest is periodically cast into the great winepress. Broadly speaking, life simultaneously consummates and consumes.

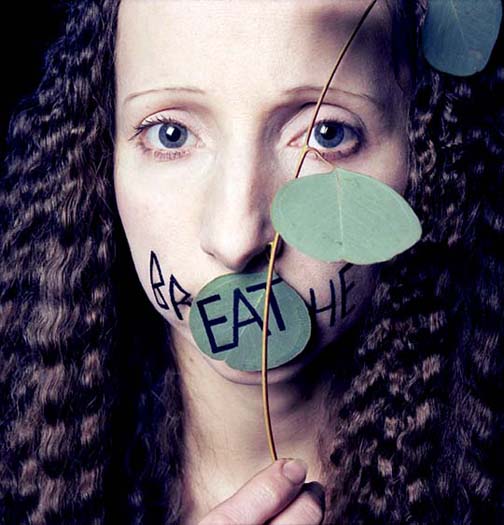

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Breathe © 1990, C-print |

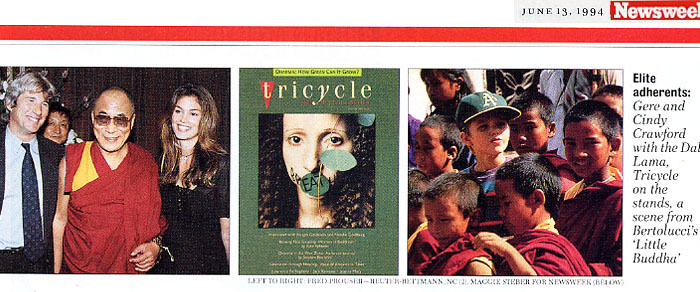

Many symbols organically emerge from the natural order and reflect that very order, which must not be understood in a straightforward manner. For example, in the photograph Breathe (1990), the act of breathing is frozen into a still performance, dissolving the boundary between the discrete movements of respiration. The nourishing syncretism of life stretches from simple breathing (the internal "eat") to abstract vital principles through which all things are made and lowly nature is filled with activity. In the artistic cloth, it disguises the old symbol of the earlier numinous tradition, namely, the vivifying spirit of pneuma. The ancient Greeks described breathing "according to its own law," that is, without an air current, similarly to prana in Hinduism. By invoking the vivifying pneuma, they hoped to transform their bodily engine into a kind of perpetuum mobile of spirit, thereby shifting to mental breathing. Despite the Renaissance undertones of Breathe, the fact that it appeared on the cover of the Buddhist review Tricycle suggests that its message is cross-cultural, at least in the respiratory sphere.

In the related work L-if-e (1990), energetic ebbs and tides are shown differently. The soul is said to be "the organ of nourishment," yet full of iffyness, many and grievous pains. It periodically loses its breath and energies amid cross-purposes and conflicts, and yet it is life itself - "if" one is willing to admit it. However attractive life may appear to men, it fails to lack that latent pressure signaled by the ambiguous internal "if."

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, L-if-e © 1990, C-print |

The eggs are shown as the seeds that simultaneously represent the end of one crop and the beginning of another as a built-in, sustaining principle of nature. Separated by "if," they seem to contain provisional meaning with certain reservations: if only man could know the answer to the l-if-e-posing questions. Some people approach these questions with the simplicity of ABC blocks, while others prefer to see them squared, as a2 + b2 = c2 (1989). Whatever form the search for the answer might take, it seems to be an impulse devised in the character of man by l-if-e itself.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Pythagoras' Theorem ©1989, C-print |

Each separate image represents a detailed sketch for one large "painting" or rather a visual saga, testifying that dividing reality into parts is arbitrary. The work Anima-l is an example of chemical blending without bonding so that each "ingredient" retains its own property and make-up. A general libido drive manifests itself as basic habits that fortunately for animals and unfortunately for humans coincide in a great deal. Aside of various theories that aim at subordinating spirit to matter (or vice versa), the pendulum between two propositions "man is like ape" or "ape is like man" is always shifting. This pattern seems to be coded in nature much deeper than in our thinking mind. Quo animo? - With what intention? (Lat.)

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Anima-l ©1989, C-print |

With his little addition of one letter "L", cat Misha changed the whole picture, extending human anima below into the animal kingdom. Animals are extension of human souls; their codes are concealed within our DNA as their tails are hidden in our tailbones. In the shamanic tradition, and not only, there is such a phenomenon as a "power animal." These guardian spirits guide human souls through landscapes of unconsciousness, which is not necessary to understand verbatim. Various animals stood on the crossroads of different mythologies and eschatological doctrines. Goddess Bastet was not alone to have a feline appearance; the atemporal realm of the Egyptian pyramids was populated with many gods bearing different animal heads thus indicating the principle forces of nature. Presented mythologically, internal powers wore external masks of different animals, and as such being fit to familiar life forms.

Animals indeed carry our childhood within themselves; they never grow up as children do; our pets remain the same, open and innocent as babies. Both children and animals know how to play, learning it without teaching. Games are an a priori part of human nature reflected in child behavior and in art; games make us liable to creativity, stimulating and reflecting it. Nature rules her kingdom through a play of illusions allowing us to avoid her dark side using a similar magical portal. Children play life.

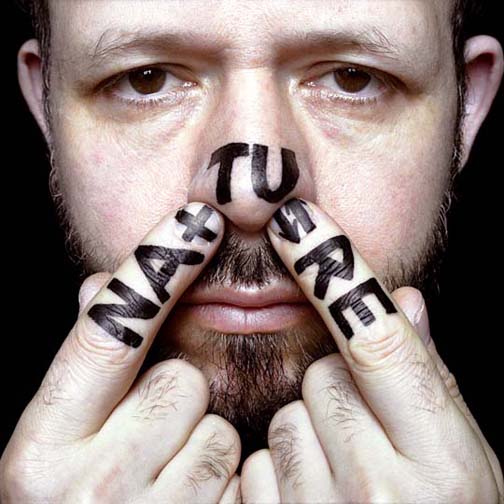

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Nature ©1990, C-print |

Human nature is continuous within the rest of nature. Some people are highly sensitive to the world around them to almost insane degree. When Friedrich Nietzsche saw how a driver abuses his cab-horse in a Turin street, he suddenly flung his arms around the neck of a maltreated animal and collapsed in tears. We carry everybody's pain upon ourselves, but only the most sensitive people know it. In a way, our nature and Nature's nature are the same nature. One thing leads to another. Perhaps, Blaise Pascal created an empirical formula saying in the Pensées: "It is dangerous to tell people of their bestial origin unless at the same time you tell them of their divine potential."

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Many Photoglyphs are reproduced in the books and the catalogs:

The Concepts, book,1012 (info) (link to the pdf)

Photoglyphs The New Orleans Museum of Art, 1993, (more...)

Still Performances, MIT, 1989.

Aqua Vitae ©1989:

Judith Bell, "Postmodern Perestroika", Museum and Arts magazine, Sept. 1990.

Florence Rubenfeld, "Rimma Gerlovina/Valeriy Gerlovin", Arts magazine, Jan. 1991.

Fish ©1987:

Andy Grunberg, "Image and Idea", preview of the new season exhibitions, The New York Times Magazine, August 30, 1987.

Carol Stevens, "Still Performances", Print magazine, March/April, 1988.

Photems by Nicolai von Kreiter, CEPA magazine, Buffalo, NY, 1988

Serpent ©1989 (link to full bibliography):

Lunation ©1990:

Amei Wallach, "Gerlovin's "Decade of Freedom", exhibition at The Fine Arts Museum of Long Island, Newsday, May 31, 1991.

Westchester Life Style magazine (exhibition "Making Faces" at Hudson River Museum), March, 1995.

Magic Square ©1987:

Book Face.The New Photographic Portrait, William A. Ewing, Thames & Hudson, 2006.

Carol Stevens, "Still Performances", Print magazine, March/April, 1988.

Tetraktys ©1989:

Book L'empire des nombre, Denis Gued, Decouvertes Gallimard, Paris, France,1996.

Still-A-Life ©1988:

Book Reflections in a Glass Eye, Works from the International Center of Photography, Bulfinch, 1999.

Real ©1989:

To Be or Not ©1989:

The New York Times Magazine, July 7, 1996, cover, pp. 4, 20-25.

David Bonetti, "S.F. Art World Knows No Season", San Francisco Examiner, June 25, 1991.

Vintage ©1990:

Jacksonville Art Museum News, Florida, June/July 1993.

Breathe ©1990:

L-if-e ©1990:

Conspicuous ©1990:

The New York Times Magazine, 7.7.1999, cover.

Odd ©1989:

The Bradenton Herald Sunday Magazine, exhibition at Ringling School of Art and Design,Sarasota, Florida, Dec. 10, 1993.

< home < content next: part 2 >