< home < content next: part 2 >

RIMMA GERLOVINA AND VALERIY GERLOVIN

PERHAPPINESS

© 2010, Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin

PART 1

All of our photographic work is divided into three main cycles: the Photoglyphs, Perhappiness, and the Photoreliefs. Technically, they differ in format: the Photoglyphs are square, Perhappiness features an array of rectangular shapes, and the Photoreliefs are sculptural works of various forms. If the Photoglyphs "speak" primarily through words and drawings, Perhappiness is a visionary development. We see the latter as a mode of existence, in which "perhaps" and "happiness" are entwined. The word "perhaps" is rather tricky, its meaning encompassing uncertainty as well as possibility. Each of us has a dose of happiness that can be characterized as perhappiness. Many live in the incessant pursuit of desires, obsessive as tail-chasing, in which the satisfaction of one wish quickly gives rise to another - a vicious cycle that calls to mind the glamorously brutal Rolling Stones melody "I Can't Get No Satisfaction." Real happiness is unconditional; it doesn't fade away with a change of situation. It's a balanced state wherein the dualism of happiness and unhappiness disappear: a treasure hard to find.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Fallen Grape © 2001, C-print. Fruit of life comes veiled in "perhappiness." |

The magical aspect of Perhappiness deals with the play of paradoxes that underlie the bittersweet scenario of life. It encodes a range of themes: the play of intuition, theurgical elements, the contemplative state, the aesthetic quest. Many of these ideas are nearly forgotten in today's culture, based on the technology of external manipulation upon matter. The human figure in Perhappiness is not so much a canvas for representation as before, but rather its initiator, a kind of mystagogue. All of these photographs feature various kinds of wonderworking.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Cross Hands © 1996, C-print |

The large-format view camera afforded us enhanced possibilities for multiple exposures and other photographic maneuvers. After making a drawing of the first exposure on the ground glass, we would expose the second image on the same negative with the utmost precision. This process involved a degree of discipline and concentration comparable to the mental focus required in the sport of archery; the live "target" could not make the slightest move for hours, so as not to spoil the multiple exposures of that literally still performance. Baroque music, most often the cantatas of J. S. Bach, was on in the background as we worked. It helped us to develop our ideas on our faces like a lyric drama or sermon set to music.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Soliciter © 2000, C-print |

Many of our compositions are weaved out of loose hair functioning as threads of life, alluding to Aphrodisiacal vitality and Samsonian strength, or deployed in the manner of the authoritative premise "The very hairs on our heads are all numbered." (1) In Bark (1997), the traveler, the bark, and the oar all emerge from a single source, embodying the Latin proverb "All my things I carry with me" (Omnia mea mecum porto).

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Bark © 1997, C-print, collection of Nasher Museum of Art, Duke University, NC (link). |

Human figures and objects, flora and fauna, fire and water, geometric shapes and origami were all created out of hair. It's the most organic material that happens to be close at hand (and on the head). In technical terms, it's a convenient and self-sufficient means of outfitting a woman; it's also the most natural and archetypal fashion that never goes out of fashion. It served us as both pseudo-garment and haircloth for penitence. Since we're inclined to work with atemporal ideas, we have to follow their rules, which demand similar mythological and metaphorical forms for their manifestation. That filamentous structure of flaxen hair, in which nature has enclothed woman, permits us to create the minimum of corporeal density, thus bringing certain exaltation of the principle of consciousness. In the later works the ideas are generally expressed silently, through the use of gestures, metaphysical proportions, and spare compositions conductive to mythical calmness. The plasticity of silence can reveal another inner space when a single word seems to be too many. (2) Overall, we don't separate aesthetic qualities from art. In the cultural and religious intensity that characterized the early arts, the benevolent side of reality was shown by harmonious qualities when the physical aspect of appearance was subordinated to the metaphysical. Socrates is credited with the prayer to give him beauty in the inward soul, and to grant him that inner and outer man be as one. Such was the iconography of the past that we wanted to recreate in our present.

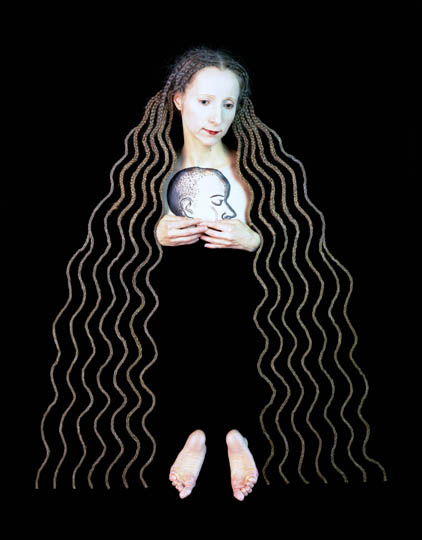

Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, The Prodigal Son © 1996, C-print There is a big difference between the prodigal son and the prodigious son, yet the evidence is inconclusive. |

It's difficult to arrive at a tangible means of expression to adequately render an intangible substance. In the photograph Prodigal Son (1996), the son exists only tentatively, and yet he's there, like the smile without the cat. Neither his real feet, nor his drawn head are strange to his would-be mother, who visually assumes the roles of both parent and offspring; the son's feet are the result of the double exposure of his mother's feet, while the son's head was drawn right on the mother's breast.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Wings of Mercury © 1997, C-print |

The subtler the thoughts, the subtler the depictions of the human figure they engender; after all, man has to be better than his body. In the series of Cutouts, the body is represented in absentia by empty space, thus achieving not only a state of weightlessness, but also invisibility. In the image Subliminal Child (1995), the latter's figure has been cut out of the photograph - he's meant to be "transparent to transcendence," to use Karlfried Dürckheim's term. The vacant silhouette casts a soft shadow on the wall seen through its outline, thus acquiring three-dimensional yet ephemeral depth. Beyond the theoretical ideas embedded into these works, it's worth mentioning how the photographs functioned in the actual world. For example, Subliminal Child and Bark were once exhibited in quite an unusual context, displayed among the original Renaissance paintings on the same perennial theme at the Duke University Museum of Art, Durham, North Carolina.

| Subliminal Child (the third from left): The silhouette of the child is cut out, 1995, C-print in stainless steel frame, 46 x 34", collection of Nasher Museum of Art, Duke University, NC. Photo of the exhibition at the museum, 2000 |

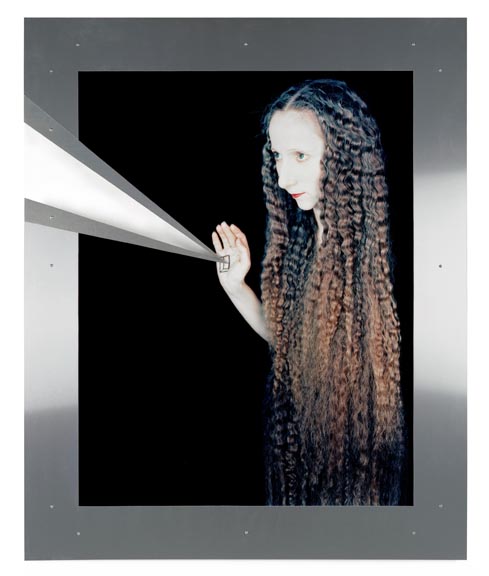

Despite their different shapes, all the cutouts serve the same purpose of rendering intangible elements like air or light, of which Slit (1998/2009) is a case in point. Focused on the palm of the hand, the ray of light is invisibly created out of the airy emptiness that's literally wedged into the physical form of the relief. Light by which we see, cannot be seen. We see only what it illuminates.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Slit © 1998/2009, C-print in aluminum con-struction, 48 x 39" |

The theme of light was developed in our art not only visually, but also in writing, yet for its backing we used our art works as usual. When we were asked to write short comments for the photograph Cherub, included in the exhibition "New Angelarium" in Moscow Museum of Modern Art in 2007, we turned them into a topic of light. The conversational voices are not supposed to be perceived by the human ear. (3)

ANGELIC DIALOGUE

Angel: Is there any light in the world? Archangel: Yes, it is, but in general there is merely lighting. Angel: Can you shed some light upon people darkness? Archangel: Only enigmatically. They block their own light by all a-vain-able means. En-chance-ment after en-chance-ment... Angel: Do we keep our light dark for them? Archangel: Not at all. For them our light is hitten madder, nothing but truebles... Our life for them is like memory of the future... a flying s-our-ce... Angel: Why is this so? Archangel: Because their la-10-nt f-8-th is 4-gotten. It is a natural order of things. Angel: In pure light, even darkness glows. Can we convert their black hole into the white one? Archangel: We have tried. We told them: "Turn inward!" They asked: "Where is in?" Their gravity curves our light. Angel: Is this penumbra eternal? Archangel: Not exactly. En-light-enment is in fact en-life-enment... and if they ... .-- . - or .-.. .. --. .... - (At this point, the dialogue is fully converted into Morse Code.) |

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Cherub, ©1996, C-print |

Gradually, we developed our discourse in the manner of the sutra. In theprocess of its own becoming it was carried out like a thread that binds together beads in a rosary (that's precisely the meaning of sutra in Sanskrit). In our case, the creative flux was akin to one long performance consisting of staccato images or rosary beads united by a single string. Each visual concept of our sutra contributes to the whole, developing the essential idea through manifold aspects, all suiting their corresponding levels of consciousness, fabricating the projections in art forms. Tentatively, they can be linked to the notion of the four elements that had widespread currency in antiquity. The mastering of each element was akin to "baptism" not only by water, but also fire, air, and earth. That quaternary operates like a revolving door, admitting men into another dimension of consciousness - one by one, or perhaps two by two, as in alchemical thought.

The figurative interpretation of the four elements clearly reflects the difficulties inherent in all great undertakings. All mythological patterns bear the residue of a fourfold phase, in which the process of building up and breaking down is accompanied by anxiety and disagreement of cross-opposites. Our works, primarily those in the Cutouts series, depict air as "the absence of presence." As for fire, it assumes a rich variety of forms.

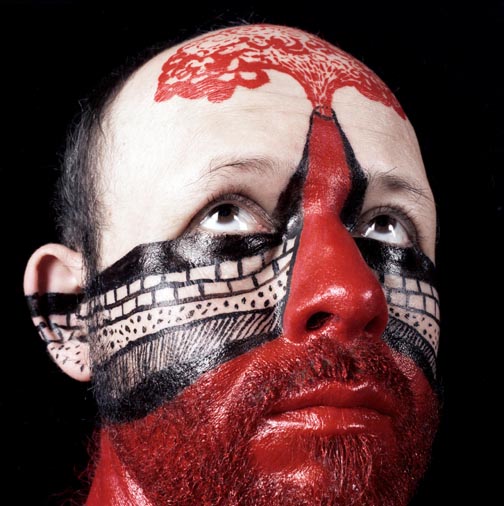

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Volcano © 1990, C-print |

In Volcano (1990), it appears as the violently powerful red lava rising through the tenebrous intermediate state of subconsciousness (both of nature and man) and erupting into the upper regions. Fire is whatever burns, cooks, shines, or transforms, like in the case of the Phoenix, and its symbolic color is red. The burning purification (tapas in yoga) can be expressed with a somewhat ecstatic state, when one is dipped in the flame as though it were water. In a dreadful and wonderful way, the rage of extreme inner heat could appear as a syndrome of the appropriation of sacrality. The natural inference would be that mental lava must be transformed into a fluid before it can be poured into new molds.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Candle © 1997, C-print |

In the mid-1990s, real fire replaced the picturesque seismic scenes depicted on our faces. The flame assumes different guises in our photographs: it's alternately a torch composed of a "phallic" finger (Candle, 1997); a personal beacon (Bark, 1997, see above); or a flaming wreath (Bride, 1997), in which the veil is also literally drawn with fire, photographed at a slow shutter speed.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Bride © 1997, C-print |

In Bride, the bottom of the veil outlines a large profile in repose, and the bride holds the flame in the "groom's" eye with her bare hand. Realized in such a "fiery" manner, the weightlessness of the latter's body signifies the type of presence that requires no further elucidation.

The place of real fire, which subsided amid the blazing tension of its expression, was gradually subsumed in our work by its conceptual depictions. First came the red roses, whose scarlet and crimson petals reverberated in the furnace of our imagination in many mosaic images. When Apuleius turned Lucius into the beast of burden in The Golden Ass, the latter was able to recover his human form only by eating roses. In alchemical terms, his personality was tempered and refined, while his Martian heat and pulsation were processed into the light - or, if we spell out it linguistically, "eros" was reconfigured into "rose."

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Invisible Bonfire © 2001, C-print. |

Washed in fire of the burning rosebush. The iconographic symbol of the rose has many twists and turns - life goes in circles, full of thorny rosebuds, Such is our Pilgrim (2000), who holds the cross of roses, the subliminal beauty of which contrasts with their thorny stems reflecting its double symbolism: love bathed in blood. In the past, this symbolism was (and perhaps still is) a metaphor for the unified consciousness transformed into the philosopher's garden - into the blooming rose cross, as in the emblem of the Rosicrucian Order.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Pilgrim © 2000, C-print |

Life goes in circles,

stuffed with thorny rosebuds.

Some of us are trying to circle the square,

some are squaring the circle of others.

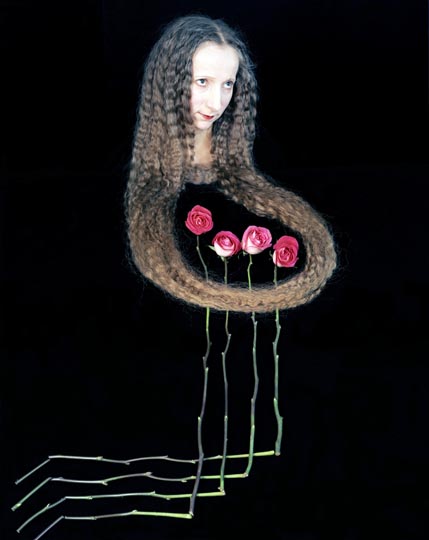

A similar motif is depicted in Kneeling (2000), in which the gift of roses rests upon thorny legs, indicating that the law of sacrifice is concealed behind all phenomena. "He who wants to enter the rose garden without a key is like unto a man who wants to walk without feet." (4)

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Kneeling © 2000, C-print |

Indeed, keeping transcendental impulses in flux is equivalent to walking on eggshells. Art seems to have special facilities for storing and "face-fully" rendering certain subtle notions that cannot be expressed by ordinary speech, thus differing from old religious texts loaded with bewildering parables. Deep-rooted knowledge is not obtainable from scholarly research or external experience; it has to be imbedded into the memory of the soul. That memory can be awakened by particular stimuli, some of which are located within the aesthetic field. In art, fundamental ideas can be transmitted visually by picture-writing. What's important is that pictography is able to represent an entire thought process at once, as opposed to breaking down an idea into components of discursive thoughts, as in writing. So Dante described his vision of bel giardino: "Here is the Rose in which the divine Word was made flesh." (5)

Nonverbal mythological allegories conceal an intriguing range of meanings. Refocusing our attention, we began to reduce words to their hidden meaning, to the silence of a still performance. The visual language of roses is particularly suited to that purpose. We used them for making crowns and staffs, converting their thorny stems into human figures, cages, and fences, arranging their petals into mosaic images of the burning bush, the philosopher's garden, and other allegorical scenes featuring bonfire, a shroud, or a maverick scarlet horse.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Hermit © 1998, C-print |

The same theme of love and blood and thus life and death continued in the series of mosaics made from the seeds of pomegranates - a fruit said to have emerged from the blood of the slain Dionysus. The pomegranate mosaics reverberate on light as rubies, inlaying weird and wonderful subjects such as the grail or the bloody veil of Persephone, who had to remain in Hades because she ate a single pomegranate seed there. Everything external is void in the composition of Hermit (1998), in which a solitary figure holds the infernal light of a pomegranate spreading its rays into darkness.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Lamb © 1998, C-print |

The mosaic banner of Lamb, after Dürer (1998), lilts with crimson red, while the golden fleece of the lamb is made out of hair. Rimmon, the Hebrew word for "pomegranate," was supposedly carved on the columns of Solomon's temple. The "apple of many seeds" (pomum granatum in Latin) was frequently depicted in the hands of Madonna, and before her Aphrodite and Hera, signifying not only the fecundity of nature, but the oneness of the universe when the seeds of the multiple and diverse are reconciled in the single red "globe" of the pomegranate.

| Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin, Oil Lamp © 1999, C-print |

< home < content next: part 2 >