Jean Brown Revisited

by Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin

There is no straight line as such, if you draw a line continually over the surface of the earth, it will be a circle. That is how we should ‘circumscribe’ Fluxus mentality. Following the similar straight and winding line of our life, we came to the door of the Shaker Seed House in Tiringham, MA, in May 1980. Seemingly, all things have had arranged themselves quickly and favorably for that matter. In February, we moved to New York from Moscow (after lingering for some time in Europe); in March, our friend Italian visual poet Mirella Bentivoglio came to New York and connected us with Jean Brown, collector of Dada, Surrealism, and Fluxus. The first two days we spent at Jean’s house, that had been built by the Shakers, were almost revelatory – we suddenly met the person whom we knew from illo tempore, the mythical ‘now’ that is stretching through past and future. The true reason for any deep connection lays in that ‘immemorial’ familiarity between the people, a kind of familiarity that would be intelligible only to faithful affection. From here on Jean became our good friend, an advisor on many matters, and probably a person who left the most memorable impression on us with her exclusive kindness. And that particular quality is most rare, which we were destined to learn later when encountering its overpowering opposite.

We begin our little story about Jean Brown with describing her landmark feature. If each man should be a law unto himself and follow the teaching of his heart – Jean was one of such people, she always followed the natural tenderness of her heart, filled with gentle benevolence, but void of sentiments. Either by accident or by ordinance she always said to people the kindest words. She used to call Mirella ‘My Italian Princess’ (that was literally true), for Rimma she reserved an artistic title “My Botticelli Girl,” and her alley cat got a figurative name “My Whisky Bottle.” Her attitude had not been formed only by the nice social manners, or by that type of friendliness that feeds on the alternative motives.

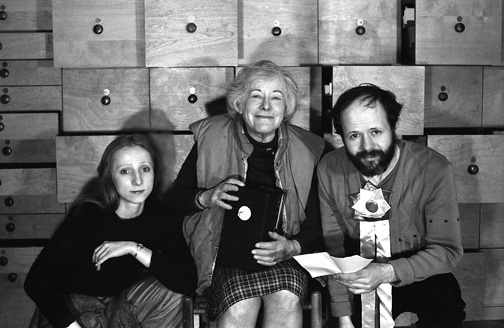

| Valeriy Gerlovin, Jean Brown, and Rimma Gerlovina at Jean's house, 1980 |

On the whole, she was outwardly wrapped in her own kindness that prevented her from being damaged by other people. At least that was our impression, which may or may not be contrary to reality. She had achieved what is called in technical terms, the disarming power of a smile. Indeed, before the tongue can speak from the heart, it has to lose the ability to wound. While the majority of people tend to decide everything by mind, she was unique in her orientation in the world, at least in our experience - knowing by love that which is usually known by understanding. At the same time, her attachment to people was not without the discrimination, her benevolence was fully conscious, based on the independent judgment that was never expressed by harsh words. For example, she was very fond of John Lennon, but quite indifferent to the fame and power inherited by Yoko Ono; both of whom she knew personally. As we noticed later, most people repeat other people opinions usually determined by fame; and the same hierarchy of viewpoints operates in the art world, it is merely polished by artistic liberty. In that sense, she was determined but poised and quiet about her views.

Thinking back about Jean Brown, It seems to us that the clue to our relationships was in our immediate, spontaneous reaction to her collection. Seeing how we were overwhelmed with her house of wonders stuffed with all kinds of aesthetic absurdities, she was thrilled and filled with similar joy. That is an old-aged formula of giving-taking relationships. Happiness is always mutual, even if it is just a ‘perhappiness.’ Probably, her friendship with George Maciunas had a similar basis – in natural spontaneity and simple sincerity. “Just like George” – she used to mutter softly every time she felt nicely about something well done or well said. Later we met many Fluxus artists, but unfortunately, not him - he died before our arrival in New York. George was a pivotal figure both in her collection and her placid memories that were occupied by his irrepressible vital spirit. Thanks to her memories and tongue in cheek accounts on Maciunas’ adventures by Jean Dupuy, we developed a great sympathy to this wonderful artist and a “solder of misfortune” in the struggle of Soho loft-development policy. Frequently we had a feeling that with our enthusiasm we revived his spirit in Jean’s life. She used to stress that George was also half Russian by his mother side. A former ballerina in her later years she worked as a secretary of Kerensky, the ex-head of the Russian provisional government in 1917. Aside of the national and aesthetic affinity, the single fact that after seeing Jean Brown collection we bluntly said in our rudimentary at this point English “Fluxus is Maciunas” seemed to contribute immediately to our friendship. Probably for many Fluxus artists our quick affirmation would sound as much blasphemous as the statement of Nietzsche for the churchgoers that “there was only one Christian, and even he was crucified.”

Jean Brown in a Fluxus robe designed by George Maciunas in front of the cabinets also designed by him especially for her collection. Photo © 1980 Gerlovin |

One could find in this collection objects suggesting all kind of hypothesis mixed with all kinds of facts, which made the mind exercise by imagination. Some works remained in our memory such as a black metal box made by Joe Jones in which two metal worms were chasing each other in a circuit. They produced a funny buzzing sound, called by the author ‘flux music.’ It was a cause-and-effect game when one inevitably follows the other. We remember how Jean pulled up the chain of metal letters made by George Brecht, spelling them into ”this sentence is weightless.” It was like having an intention and not having one. We tried our luck touching the unidentified content in the tactile boxes of Ay-o. It left the strange feeling that inside and outside are made to invert and contain each other. Ben Vautier in his Flux Suicide Kit instead of regarding the tragicomic content of the world in a gloomy manner, suggested a more light-hearted absurdist way, maybe even laughing about it as Voltaire used to laugh in order to “keep himself from going mad.” Jean told us the story behind the little Fluxplane - Stalingrad by Nam June Paik. He presented it to George Maciunas, who was dying from cancer, promising him that he will return to them as the Red Army returned to Stalingrad. “But the Red Army never left Stalingrad”- answered Maciunas.

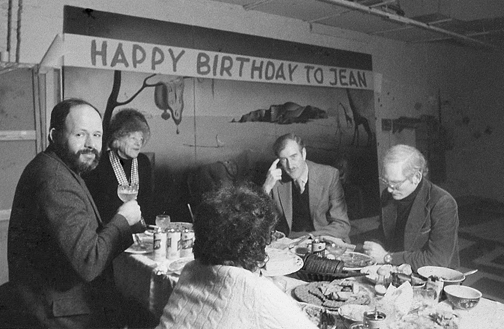

Recollecting those privileged moments that we spent with Jean, one occasion stands out. In December 1981, she gently suggested to celebrate her birthday at our garage-loft on Spring Street. Jean rarely went to New York, and this anniversary was an excuse from her regular habit. She insisted that she would bring everything and everybody along. Her escort consisted of her son and Peter Frank. Needless to say, we were happy to host her in our place crowded with the art works, ours as well as others. We remember how somebody joked that coming into our loft he felt like Alice entering the rabbit hole when she suddenly appeared among the spectacles and wonders of another dimension. Nor was this all. Upon her entrance, Jean was astonished by the large painting by Salvatore Dali crossed by the banner “Happy Birthday to Jean.” This painting made for the Art Fair in 1939 consisted of four 99” x 47” panels; it came into our hand for restoration, following a trajectory as mysterious as Dali’s art itself. (For many years in New York, we supported ourselves with this traditional craft of ‘curing’ other artists’ works.) Jean was thrilled. It was in the spirit of her own collection of Dada, Surrealism, and Fluxus. The synchronicity of events occurred seemingly for that special occasion of her 70th birthday, and we simply cohered with it by means of ‘surrealistic’ twists of fate. It went along with her taste reflected in her uncommon interests in art full of surprises.

Jean Brown’s Birthday. From left to right: Valeriy Gerlovin, Jean Brown, sitting under the tree with Dali’s Liquid Clock, Pauline Ores (back), Jonathan Brown, her elder son, and Peter Frank at our loft in Manhattan. 1981 |

One more unusual feature of her character attracted our attention. Many years she lived alone in a rather remote house in Massachusetts. The very first evening we spent with her, she unexpectedly said to us: “Stay away from New York.” Seeing our surprised faces, she made a gesture like she said something of no importance. How could we understand the meaning of her words arriving in New York only three months ago? At this moment, we reasoned not: the time was not ripe for this. She simply read our future. Only later, in 1993 when we moved out of the city did we fully understand her words about New York that she seemingly dropped accidentally many years ago. “From Quaker Road (our new address) to Shaker House…” was the opening line of our last letter to her. But in the Eighties, she was listening to our stories about the art world in the metropolis and its perplexions with sad silence, without any comments. The world is a great mart, and it would be a waste of energy to analyze it or to argue against its casuistry. Everything has followed the natural course of events, and she knew it. As for herself, Jean has chosen to live alone surrounded by nature, without losing much energy in social cross-purposes and conflicts. Often people are worldly because they know no better. Jean seemed to manage the scales between natural and social balance. She has chosen the way of life that can be characterized as inward and outward simultaneously, progressively becoming mindful and self-possessed and at the same time friendly and opened to many artists who came to see her collection and to add to it something of their own.

We do not want to go into descriptions of her collection, her house, or other empirical realities, instead, we try to look at certain forms of insight and bring them into conscious operation. Her unusual answer to our question “How is she managing alone?” took a strong hold in our memory. “I am not alone. I am with my thoughts,”- was the reply. Her radio was always on, tuned to the classical music station, which soft continual sounds environed all rooms of her house with frequent interruptions by news. Observing the changes in her own character, she admitted that she has become much more attracted to her religious roots. Probably she felt that she must return to her own essence, to preserve her identity, and recover the understanding of her own nature. Needless to say, not everybody can face a lifetime of solitude, to be set apart by nature to live alone. Once at the very beginning of the nineties, she telephoned us and suggested us to move to her house, to live and work there. It was clear that Jean is very much alone and it has become difficult now. In compensation of her solitary way of life, Jean used to receive bunches of letters and parcels from all over the world daily. She had an enormous correspondence. A great deal of her archive and to a certain degree, even some part of her collection was built through the mail.

Jean Brown’s treasures were collected with an exclusive aesthetic intelligence, and it seems to us, certain ethical perception. Every time we visited her, we found something new in her multitude of draws and boxes full of unpredicted conceptual curiosities. As soon as she sensed that her effort to share her vision was sincerely appreciated she was very happy because she found the meaning of her life in this sharing. Trusting intuition pure and simple, Jean discovered the meaning of this “artless art,” then deepened it for herself and made it clear and meaningful for others. Just like an alchemical evocation “deepen, widen, and subtilize.” If we keep in mind that the boundaries of the aesthetic do not hold now, being transgressed and broken down, we can view her peculiar choice of the works as highly personal, yet expressing a collective experience - not overly sophisticated, but subtle like Jean herself in her psychological implications. With age, many people come to think that all deep things are simple. To this, we can add from the account of Albert Einstein who said that “everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.” Indeed, Jean’s self-expression was clothed in language adapted to the ordinary understanding, at the same time her collection was the most extraordinary in terms of taste, erudition, and eccentricity. Her holdings were processed by her life and finally reabsorbed through the eyes of other people.

For many fellow artists, she was the mother figure, the sustainer and a home-based art center, where the most human approach was guaranteed. It requires a great deal of creativity inside to be supportive to creativity of others. The art of seeing is a prerequisite of all other forms of art. Above all, the notorious egoism of many artists with their contractive self-love was counterbalanced by her friendly altruism. Therefore, the news that she is selling her collection to the Getty Museum left many artists to be wrapped in speculation. From one point of view, the artists were losing their favorite patron, from another; she was securing the further life and location of their art. As Jean told us, she has required that all her collection without a single exception will be taken by the museum not only the market-valued art - but everything and by everybody.

| Jean Brown at her house, on the second floor. Photo © 1980 Gerlovin |

One meets the facts but does not know soon enough what to make of them. In the long run, her decision was proved correct and made in favor of impersonal aims. As much as it was in her power, she assured the preservation of the artworks from her collection before she was parted with it. At that point, she asked us to make a video of her collection and the interior of the house before it was to be packed and shipped to the Getty Museum. As close standing witnesses of this situation, we were compelled to notice that along with the parting of her treasures she gradually entered a state of apathy, started to lose interest, and maybe some personal meaning of her life. She was aging, and to keep the collection and correspondence was very difficult. In 1988, we made several trips to Tiringham. Shooting the funny objects, the exterior, and the interior of the multitude of the draws filled with the peculiar stuff, we made probably the last havoc before the packing of the collection. Jean did not have much energy, and we felt we are asking too much from her trying to put her in different positions among the objects in front of the camera. Mark Bloch made the editing of the video and the soundtrack created by John Cage, also a long time friend of Jean. Everything was done rather quickly and spontaneously, as a visual memento or a small diary about this remarkable person and her collection. Unwillingly, we participated in this quiet process of “letting go”; Jean was moving into a new mode of being. “Just like George!” were her final words after the screen went out.

In our last conversation by phone, she said, “I am tired.” That was her response to our questions about her health and everything else. One week later, she passed away, moving from the state of visibility into the hiddeness; may we say, moving into space independent timing, or maybe into time independent spacing. Perhaps we shall meet again; wherever it is that we go to.

Rimma Gerlovina and Valeriy Gerlovin © 2006

The video Not Jean Brown was screened at The Emily Harvey Foundation 537 Broadway #2 New York, NY 10012

Saturday, February 22nd, 2019 – 7PM

Not Jean Brown: Dada, Surrealism, Fluxus, etc.

Premiere of a ½ inch color video by The Gerlovins and Mark Bloch, 16 min with sound track by John Cage and works by George Maciunas, Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, André Masson, Joe Jones, John Cage, Yoko Ono, Robert Watts, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Filliou, Geoff Hendricks, Nam June Paik, Christo, John Lennon, George Brecht, Ay-O, John Furnival, Dieter Roth, and others.

Preceded by videos: The Concepts, The Gerlovins, 16 min, 2012 and A visit with Collage Artist John Evans and the Avenue B School of Art, Mark Bloch, 28 min, 2004 Saturday, February 22nd, 2019 – 7PM The Emily Harvey Foundation 537 Broadway #2 New York, NY 10012 Admission is free

From left to right: Rimma Gerlovina, Jean Brown, and Valeriy Gerlovin at Brown's house, 1980. Photo: The Gerlovins.

The Emily Harvey Foundation is pleased to present the world premiere of NOT JEAN BROWN, a 16-minute portrait of the Massachusetts art collector, Jean Brown (1916-1994), some 35 years after it was originally begun in 1985. Though a finished copy exists in Brown’s vast archives at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles, the project has never been screened for a New York audience or any audience, really, despite it being a pet project of the eccentric art lover who was excited to document her collection. The subtitle of the film is “Surrealism, Dada, Fluxus, etc.”

The original footage for NOT JEAN BROWN was shot by Rimma and Valeriy Gerlovin on ½” video at Brown’s home in a former Shaker Seed House in Tyringham, a small town in the Berkshire Mountains near Lee, Massachusetts. Brown enthusiastically encouraged the Russian couple to collaborate with artist, musician and video editor Mark Bloch, a friend of both Jean Brown and the Gerlovins, to formally bring the project to fruition, prior to Brown shipping her entire beloved collection to Southern California following her arrangements for placing it with The Getty Research Institute. At Brown’s request, Bloch then contacted John Cage to help create a soundtrack for the work.

The result is NOT JEAN BROWN, a quick, personal portrait of the art collector, a group effort cobbled together by a few of her friends. The Gerlovins tested out their new home video equipment to shoot Ms. Brown and a tiny portion of her extensive holdings during one visit. Fluxus founder George Maciunas, who moved nearby a few years before his death in 1978, had custom built Brown a beautiful room to display her unique works. Though she kept everything from collages by Max Ernst and other art superstars to tiny oblique works sent by unknown practitioners of the mail art network in the dozens of wooden drawers that Maciunas built for her, this film mostly features the work of Fluxus artists. A fully documented video accounting of the work she amassed would have taken years to create professionally. So instead what we see is something that reflects the quirky, friendly personality of the owner: a somewhat roughly cut together collection of sometimes fuzzy clips shot on consumer equipment with a spontaneous voiceover by Brown. The soundtrack “Sink Sound (for Jean Brown)” is a “music of contingency” that Bloch recorded at Cage’s loft on 6thAvenue in Manhattan one afternoon when Cage’s plumbing was acting up. Cage asked Bloch to come right over so that the sounds could be used for the Jean Brown project.

Like a great many other artists, both Bloch and the Gerlovins have written and made art about their friend Jean, a gracious hostess and generous supporter of avant garde artists. The Gerlovins said about her: "Jean Brown’s treasures were collected with an exclusive aesthetic intelligence, and it seems to us, certain ethical perception. Every time we visited her, we found something new in her multitude of drawers and boxes full of unpredicted conceptual curiosities. As soon as she sensed that her effort to share her vision was sincerely appreciated she was very happy because she found the meaning of her life in this sharing. Trusting intuition pure and simple, Jean discovered the meaning of this ‘artless art,’ then deepened it for herself and made it clear and meaningful for others. … Indeed, Jean’s self-expression was clothed in language adapted to the ordinary understanding, at the same time her collection was the most extraordinary in terms of taste, erudition and eccentricity. Her holdings were processed by her life and finally reabsorbed through the eyes of other people."

Roberta Smith wrote in her obit about Brown May 4, 1994:

Jean Brown, a collector of Dada, Surrealism and Fluxus, died on Sunday at the Berkshire Medical Center in Pittsfield, Mass. She was 82 and lived in Tyringham, Mass….Sometimes called the den mother of Fluxus, Mrs. Brown possessed a natural openness to new art and counted among her friends such avant-gardists as Marcel Duchamp, John Cage and George Maciunas, the leader of the Fluxus movement.

Mrs. Brown, whose maiden name was Levy, was born in 1911 in Brooklyn. Her father was a rare-book dealer who enjoyed taking his daughter to museums. She briefly attended Columbia University. In 1936, she married Leonard Brown, an insurance agent. They settled in Springfield, Mass., where Mrs. Brown worked as a librarian.

In the late 1950's, after collecting Abstract Expressionist paintings, the Browns began to acquire Dadaist and Surrealist art, manifestoes and periodicals. They soon moved on to Fluxus, a new, irreverent art movement that stressed multiples, printed ephemera, posters, newspapers and mail art.

After Mr. Brown's death in 1971, Mrs. Brown moved to Tyringham, and expanded into areas adjacent to Fluxus, including artists' books, concrete poetry, happenings and performance art. Her home, originally a Shaker seed house, became an important center for both Fluxus artists and scholars, with Mrs. Brown alternately cooking meals and showing her guests her collection. Activities centered on a large attic archive built by Mr. Maciunas."

In 1985, as the Jean Brown Archive approached 6,000 items, it was bought by the J. Paul Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities in Santa Monica, Calif. This was among the first collections of 20th-century material acquired by the center.

(from NY Times, “Jean Brown, 82, Avid Collector Of Dada, Surrealism and Fluxus" By ROBERTA SMITH, MAY 4, 1994).

The Concepts, The Gerlovins, 16 min, 2012 Coinciding with their book Concepts published in Russia in 2012, their art is grounded in playing with paradoxes and is rich in metaphor, language and symbolism. They frequently use their bodies as a surface for psychological experience. Male / female features are part of their metaphorical games toward a theatre of consciousness. Their philosophical and mythological implications are also reflected in their theoretical work and writings.

A visit with Collage Artist John Evans and the Avenue B School of Art, Mark Block, 28 min, 2004 Mark Bloch presses the late collage maestro John Evans for details of his various techniques regarding his decades of work with daily collage/diary works.

Rimma Gerlovina (American, b. Russia 1951) and Valeriy Gerlovin (American, b. Russia 1945) were founding members of the underground conceptual movement in Soviet Russia, described in their book Russian Samizdat Art. Since coming in America in 1980, they had many personal exhibitions in galleries and museums, including the Art Institute of Chicago. The New Orleans Museum of Art launched a retrospective of their photography (Photoglyphs), which traveled to venues in fifteen cities. Group exhibitions include: The Venice Biennial; Photography of Inventionin Smithsonian’s National Museum of American Art, Washington, DC; 100 Years of Avant-Garde in Central and Eastern Europein Bonn Kunsthalle, Germany; The Polaroid Collection in Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography; Russia!in the Guggenheim Museum, New York and Bilbao, and others. Books featuring their works: Art on the Edge and Overby L.Weintraub,Reflections in a Glass Eye(ICP and Bulfinch Press); also art history college books such as Understanding Art by Lois Fichner-Rathus (Harcourt College Publ.), Making Art, and Criticizing Photographsboth by Terry Barrett (McGraw-Hill), or Art Since 1940by J. Fineberg (Prentice Hall). Their works have appeared on the covers ofThe New York Times Magazine; Zoom; The Sciences; The Buddhist Review Tricycle. In the Millennium Issue on art, The New York Times Magazinegave them a spread. Important Museum collections include: The Center Georges Pompidou, Paris; The Tate Gallery, London; The Guggenheim Museum, The Art Institute of Chicago; The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles; International Center of Photography, New York, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Cincinnati Art Museum; Denver Art Museum; Nasher Museum, Duke University, Durham, NC; The Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, AZ; National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia; Museum Moderner Kunst, Vienna, Austria, and others.

Mark Bloch (b. 1956) is a writer, curator, historian, videographer, public speaker and pan-media artist living in Manhattan whose work uses visuals and text to explore ideas around long distance communication. Since 1977 Bloch has done performance art in the USA and internationally. An archive of many of Bloch's papers including a vast collection of Mail/ Networking/ Communication Art ephemera is part of the Downtown Collection at the Fales Library of New York University, which will present an exhibition of his work in April 2020. Bloch is the author of Robert Delford Brown: Meat, Maps, and Militant Metaphysics, published by Cameron Art Museum, Wilmington, N.C. (2008). His writings on art have been published by the Brooklyn Rail, Whitehotmagazine.com, ABCNews and others. He was a contributor to Conversing with Cage (Richard Kostalenetz, editor, 1988) and Most Art Sucks (Walter Robinson, Editor 1998). Bloch organized and curated the Cavellini Festival in November 2014 at the Museum of Modern Art, Lynch Tham Gallery, White Box Art Center and Richard L. Feigen and Co. His lecture, “Jungflux Finger Storąge Box for Ay-O” was performed at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago in 2011. In addition to his work as a writer and fine artist, he has also worked as a graphic designer for ABCNews.com, The New York Times, Rolling Stone and elsewhere. Bloch has degrees from Kent State University and Baruch College, City University of New York in Broadcasting (1978) and Digital Marketing (2013), respectively. A solo exhibition of objects, paintings, collages and assemblages “Secrets of the Ancient 20th Century Gamers” was presented by the Emily Harvey Foundation, New York, March 18-April 2, 2010.

Video Not Jean Brown in The Internet Archive